What are the chances that there are two men named Ioannis Konstantinos Laliotis living in Magoula, both of whom married women named Georgitsa Giannakopooulos (father Paraskevas) living in Theologos? Although this seems improbable, the documents should answer the question. But in this case, it wasn’t that easy.

Let’s dig in.

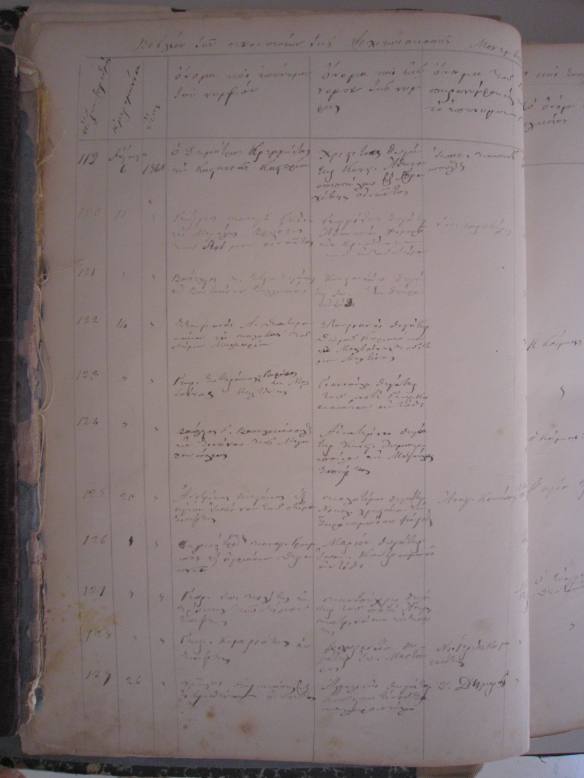

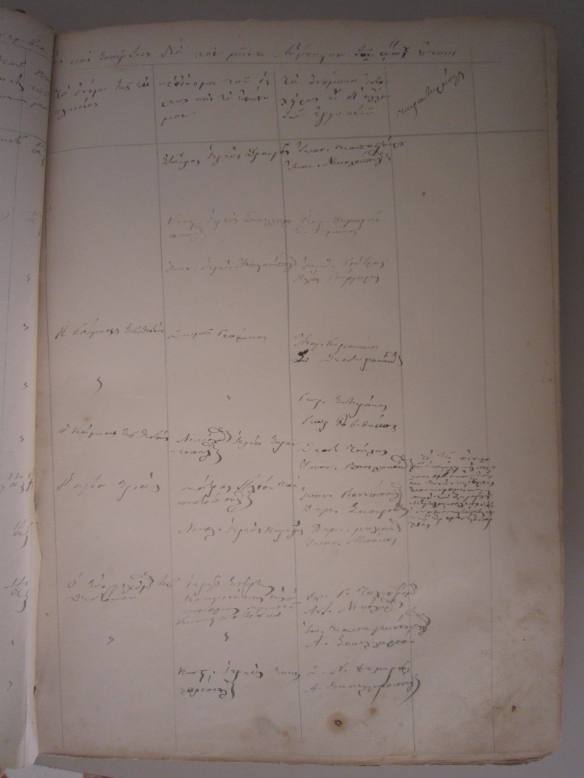

In the Metropolis of Sparta Marriage Index Books, we find that a marriage license was issued on June 28,1898: Entry #237, Ioannis K. Laliotis of Magoula, Sparta; his first marriage (A) & Georgitsa Par. N. Giannakopoulos of Theologos, Sellasia; her first marriage (A).

Available on MyHeritage at this link.

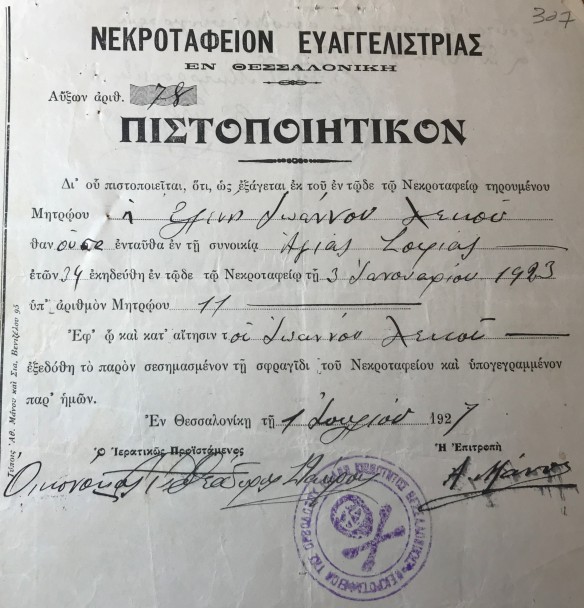

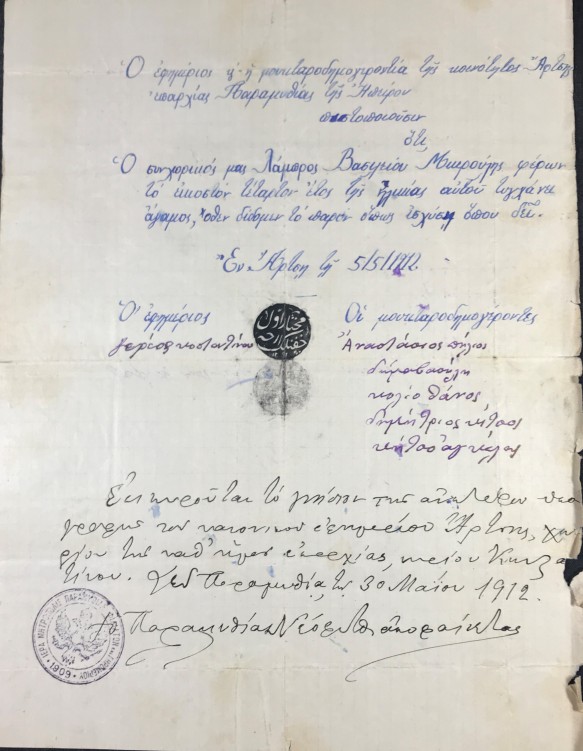

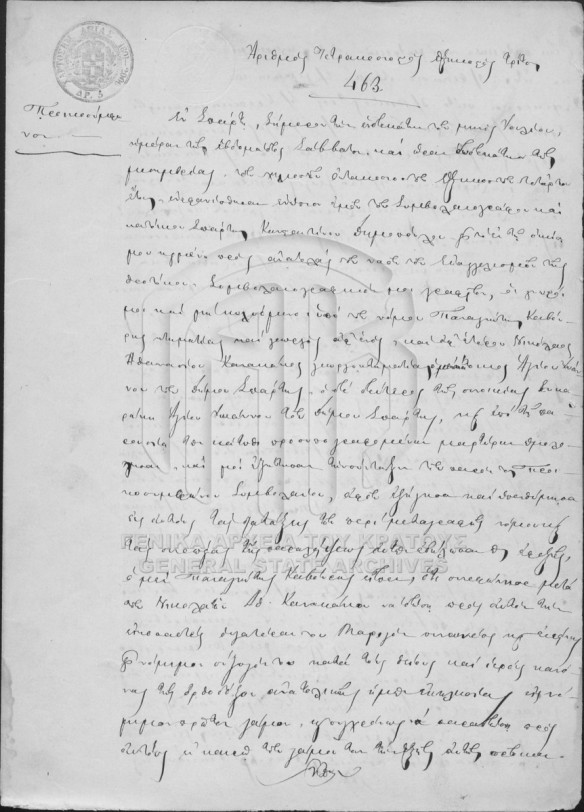

There is additional documentation in the form of the priest’s letter to the bishop, requesting permission for the marriage. In this document, we see the groom was age 22 and the bride was age 19.

In books where both the license date and the marriage date are given, there is usually just a one or two day difference between the date the license was issued and the date of the marriage. In this case, there is no marriage date given. Possible reasons: (1) early books do not have a column for a marriage date to be written; (2) the bishop’s letter agreeing to the marriage, and the priest’s response giving the date of the ceremony have not survived; (3) the marriage never took place. In this last scenario, it is quite unusual for a license to be issued and a marriage not to occur.

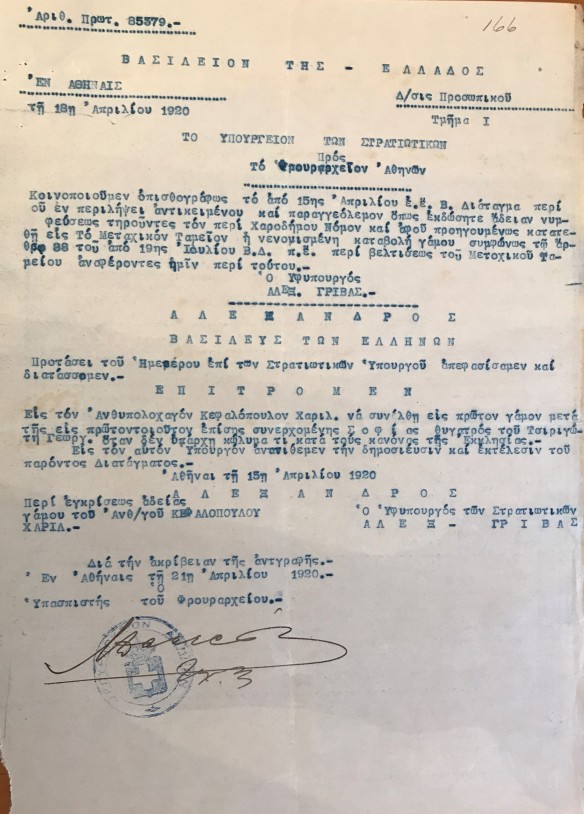

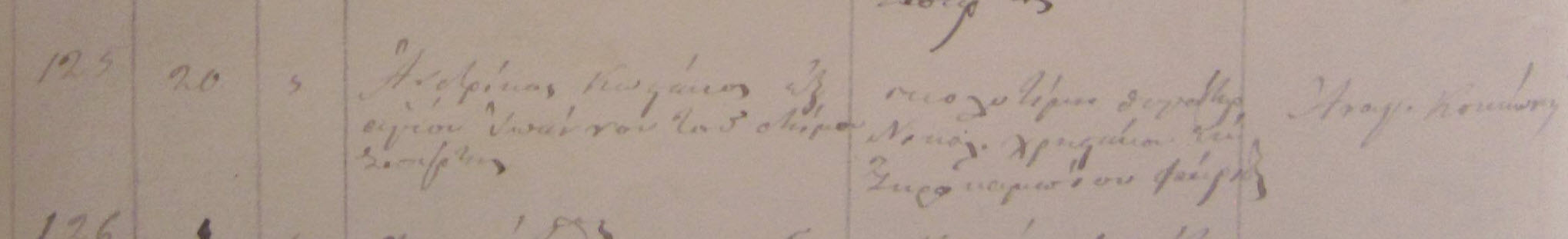

Let’s look at the second set of documents. In the Metropolis of Sparta Marriage Index Books, we find that a marriage license was issued on April 20, 1900; Entry #105, Ioannis Laliotis of Magoula, Sparta, (no father given); his first marriage (A) & Georgitsa Par. Giannakopoulou of Theologos, Sellasia; her first marriage (A).

Available on MyHeritage at this link.

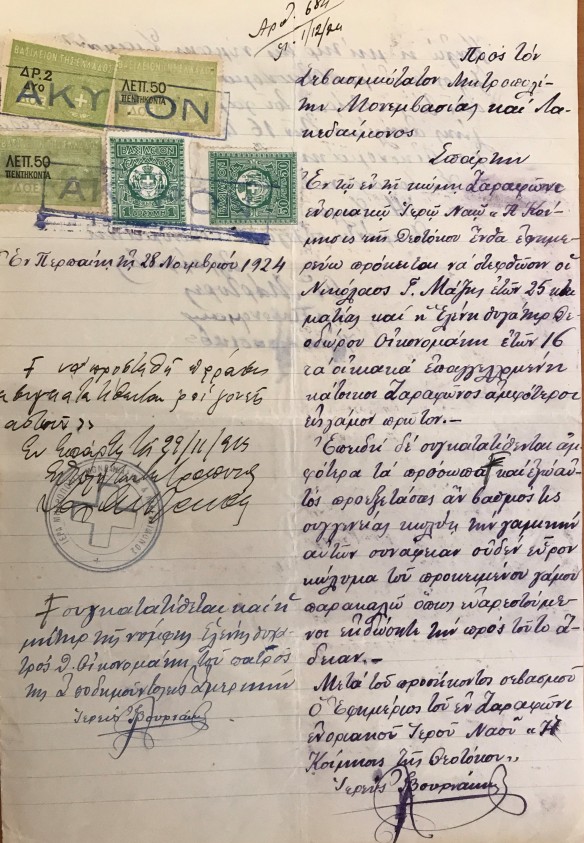

There is additional documentation in the form of the priest’s letter to the bishop, requesting permission for the marriage. In this document, we see the groom was age 25 and the bride was age 22. HOWEVER, there is an indexing error in this record on MyHeritage: Giannakopoulou was transcribed as Giannopoulou.

Looking at the “bare bones” information in these documents, we can easily discern that:

- The 1898 index book entry gives Ioannis’ father’s initial (K), and a fuller description of Georgitsa’s father as Par. N. The 1900 index book entry does not give Ioannis’ father’s initial or the initial “N” for Georgitsa’s father. And, Giannakopoulou was transcribed incorrectly as Giannopoulou. Without their father’s names or initials, and with the transcription error, these could easily be two different couples.

- The 1898 index book entry shows this is the first marriage for both the groom and the bride.

- The 1898 priest’s letter gives the groom’s age as 22 and the bride’s age as 19.

- The 1900 index book entry shows this is the first marriage for both the groom and the bride.

- The 1900 priest’s letter gives the groom’s age as 25 and the bride’s age as 22.

Thus far, it appears that these are, indeed, two different couples. BUT, my suspicions were raised because the difference in ages corresponds to the difference in the two license dates; and I know the demographics of the families in these villages.

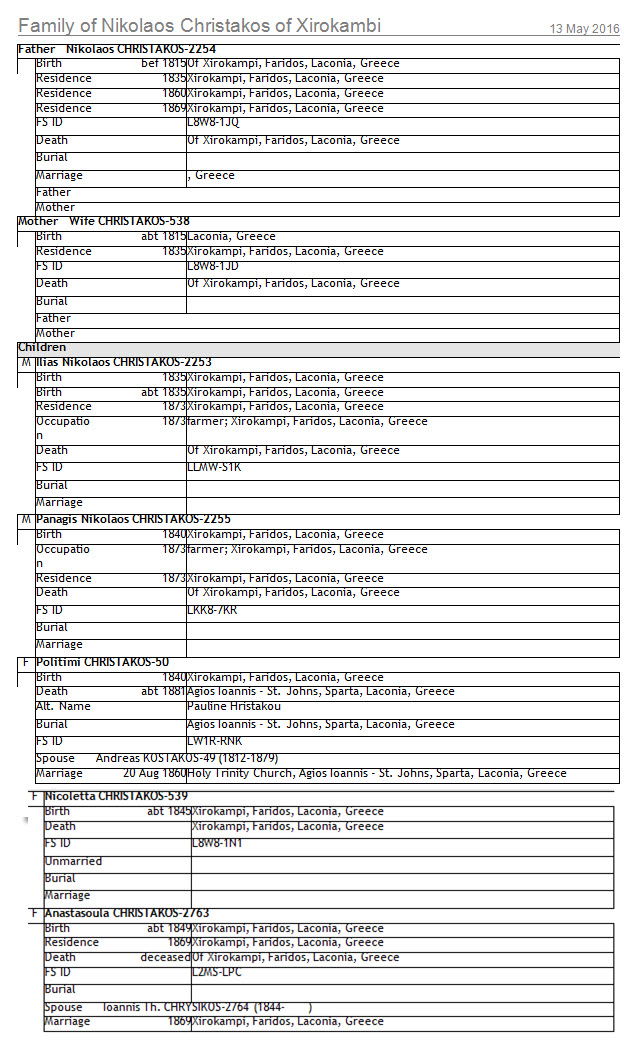

- I have the Town Registers for both villages. In Magoula, there is only one Laliotis family and only one Ioannis, born 1876, who is the son of Konstantinos.

- In Theologos, there are many Giannakopoulos families; however, there is only one Paraskevas Nikolaos Giannakopoulos and only one Georgitsa Par. N.

- The Sparta Town Register, Family #245, recorded the family of Ioannis and Georgitsa, and provided the marriage date of April 20, 1900 in Theologos. There is no other Laliotis-Giannakopoulos family named.

So, how could there possibly be two marriages?

I believed the answer lay in the priest’s letters. I cannot read old Greek script so I asked Gregory Kontos of GreekAncestry.net to review them. He said that the the priest’s letter dated 1900 contains unusual language: “this will be the first (or the second) marriage for the couple.” That’s strange wording! Although a license was issued in 1898, that marriage did not occur. Greg gave possible scenarios such as: an issue with the dowry, or possible migration if the groom left the area temporarily, with the marriage postponed until he returned in 1900. Anything could have happened to delay the nuptials.

Analyzing this situation led me to several conclusions:

- A marriage license does not equate to a marriage occurring.

- The documents associated with the marriages are important! If you cannot read them, ask Greg at Greek Ancestry, or find someone who can decipher the handwriting.

- Even though I can’t read all the words in the handwritten document, I must study it anyway. When I saw the bride’s name indexed as “Giannopoulou,” I looked for the name in the document to verify the transcription. To me, it looked like “Giannakopoulou.” I was right!

- I must find, and correlate, any and all possible records that exist for a family. A Male Register records how many men of the same name lived in the village, and their years of birth. A Town Register provides the names of the father, mother, and children. If I have a marriage license, is the couple found in the Town Register? This depends on the timeframe of the marriage, as Town Registers were created in the mid-1950s in Sparta; however, there are many fathers and mothers born in the late 1800s that are listed.

- You have to know your village and its families. I knew there was only one Laliotis in Magoula, and that raised “red flags” when I found two licenses for Ioannis Konstantinos.

Expect the unexpected! That’s the challenge of research–especially in Greece.