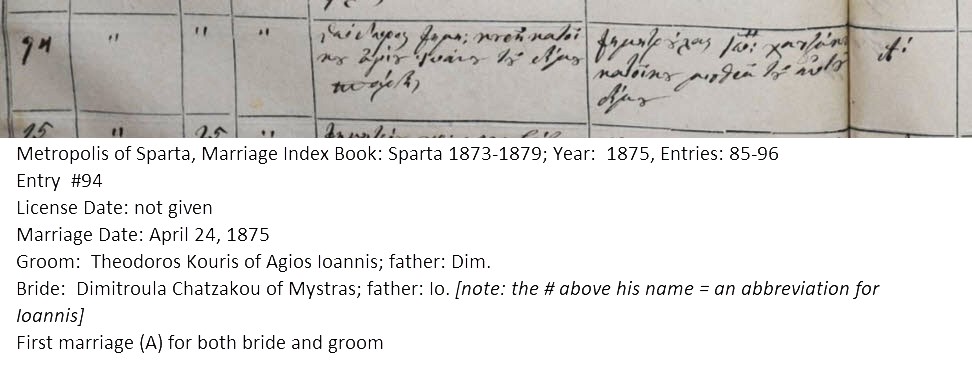

The church marriage record was clear: Theodoros Dimitrios Kouris married Dimitroula Chatzakou, daughter of Ioannis, first marriage for both, on April 24, 1875:

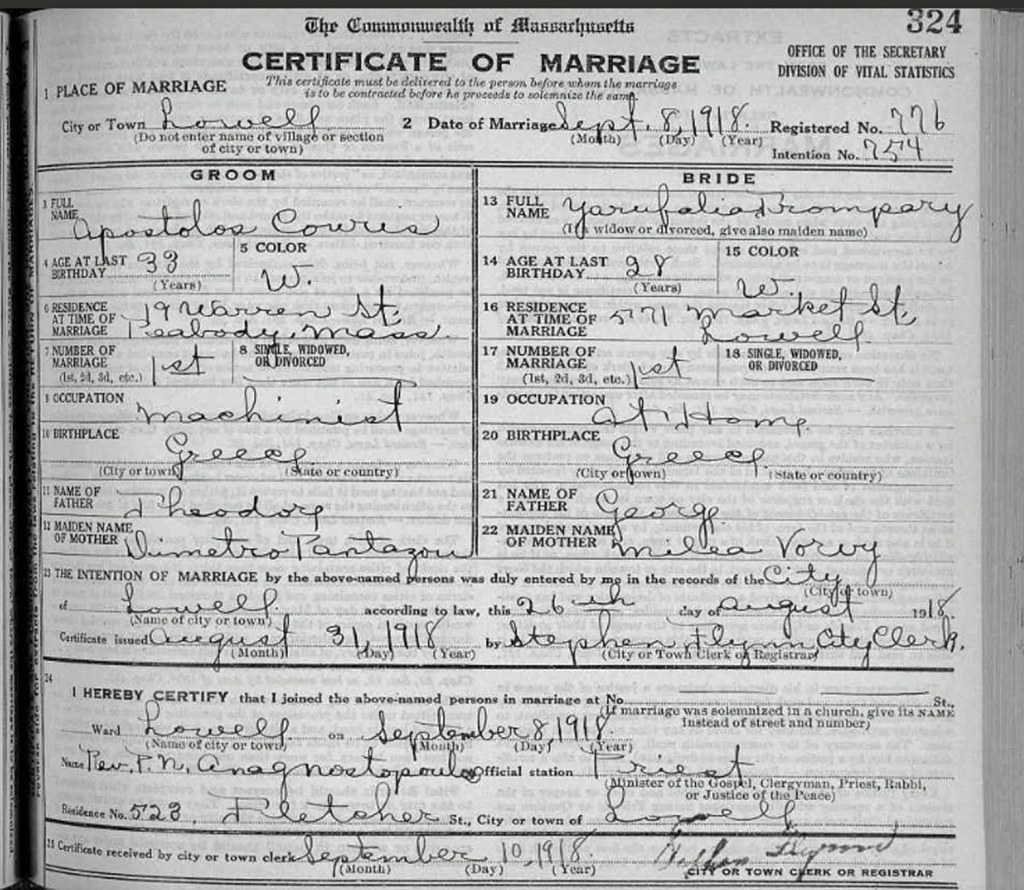

Finding this record [1] for one of my Agios Ioannis families meant that I now had the name of Theodoros’ wife and the mother of his children. Everything seemed to line up: the wedding was in 1875 and the first child was born in October 1878, although the birth (if it was a first birth) was a tad late for that time period. I entered the information in my database and to online trees at FamilySearch, Ancestry and MyHeritage. Almost immediately, hints for records in Massachusetts popped up for the children. Not unusual – many families immigrated to America in the early 1900s. I checked one of the hints, a marriage record for son Apostolos, and noted with curiosity that his mother’s name was written not as Chatzakou, but as Pantazou.

Well, the two surnames sort of sound alike. I wondered if this was a clerical error (misunderstood the name?) or a mistake on the part of the child (some are unsure of their mother’s maiden name!).

Checking further, I saw that the Pantazou surname in U.S. records was found for other children in the family. Clearly, there was a disconnect somewhere.

Because this family is not related to me, I was not planning to research this line further. (My goal is to get the Greek records online so that descendants can make the leap from the U.S. to Greece). But I felt it was important to alert other researchers to the discrepancy, so I added this note in the profiles for both Theodoros and Dimitroula: Dimitroula’s surname, according to her Sparta marriage record, is Chatzakou. However, there are records in the U.S. giving her surname as Pantazou. Either there are two Theodoros Kouris’ in Massachusetts — one married to Chatzakou and one to Pantazou, OR her surname changed in the U.S.

Before moving on to extract another family name from Agios Ioannis records, I did make one additional entry for Theodoros: I marked him as deceased and in the place field, I put “Of Massachusetts, United States.” The word “of” signifies that this was a guess, as I did not have proof of the fact.

This entry proved to be a mistake for me and a red flag for Theodoros’ geat-granddaughter , Niki, who had been researching her family and found my note in an online tree. In an email to me, she wrote:

I want to clarify another piece that you aren’t aware of. Theodore never came to the US. His wife and all of their children came around 1909….except for Nikoletta, who stayed back to care for her father, Theodore, who was blind, and unable to travel at that time. In 1920, Dimitroula returned to Agios Ioannis and planned to travel with Theodore and Nikoletta back to Boston, to join the rest of the family…However, Theodore died unexpectedly, very shortly before they were scheduled to sail. Dimitroula and Nikoletta came without him, in the summer of 1920. The ship record shows only their two names. So you might want to modify your note about Dimitroula’s surname discrepancy since Theodore was never in the United States.

Oh my! Grateful for this clarification, I quickly corrected Theodoros’ death place to Agios Ioannis.

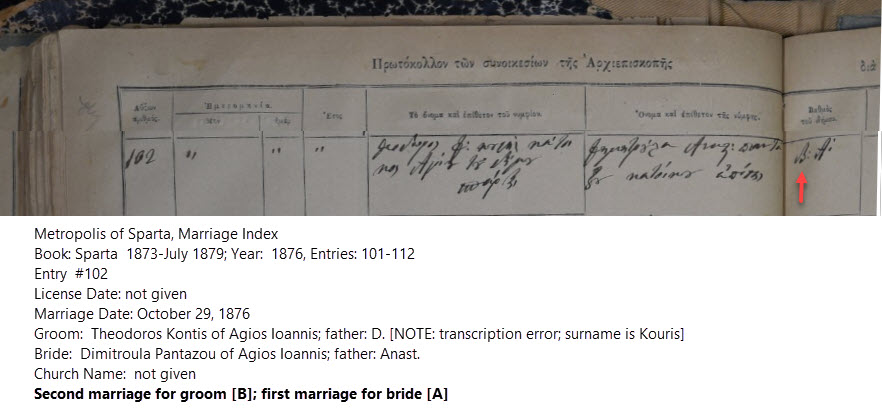

Niki had initially contacted me a few weeks ago when she found the marriage for Theodoros and Dimitroula Chatzakou online at MyHeritage[1]. She knew her great-grandmother was Dimitroula Pantazos, and the record naming Chatzakou was mystifying. Looking further and searching on “Pantazos,” she found and then sent me another marriage record which was indexed as: Theodoros D. Kontis and Dimitroula Pantazos, daughter of Anast., married October 29, 1876. She commented: “Could it be that the handwritten record from 1876 was translated incorrectly, into Kontis instead of Kouris?”

We outlined the issues:

- The handwritten Greek in both marriage records was too scribbly for either of us to clarify whether the name was Kouris or Kontis.

- This second marriage record shows it was Theodoros’ second marriage [B] and Dimitroula Pantazou’s first marriage [A].

- Their marriage occurred in October 1876, exactly 18 months after Theodoros’ marriage in April 1875.

- If this record was indeed for Theodoros Kouris, then his first wife [Chatzakou] would have died shortly after marriage [perhaps in childbirth?].

- With Georgios born in October 1878, he and his siblings would be the children of Theodoros’ second wife, Pantazou–making the 1878, exactly two years aftermarriage, birth more realistic for the times.

Clearly, the answer lay in the clarification of Theodoros’ surname. A quick message to Gregory Kontos at GreekAncestry resolved the mystery: both marriage records were for Theodoros Kouris; the second record was transcribed incorrectly.

A few points to consider from this case study:

- NEVER trust a name index!

- ALWAYS review the original record. If it’s in Greek and unreadable to you, someone else can help. Upload to the Hellenic Genealogy Geek Facebook page or send to Greg Kontos at GreekAncestry.

- Search a variety of records to verify information. In this situation, looking at U.S. records for several of Theodoros’ children revealed the same mother’s name. This raised the chances that the children were correct, and the possibility that there was either an error in the marriage record or a second marriage for Theodore.

- Document facts that don’t correlate, and make sure those notes are attached to each individual that is affected.

- If you are making an assumption, state what the assumption is and why you are making it. I did not do this for Theodoros’ death place when I listed it as Massachusetts.

- Theodoros had two wives with the same first name, which caused incorrect assumptions. The children’s baptismal records in the village church book gave their mother’s name as only Dimitroula (no surname) which caused me to assume that the Chatzakou record was correct.

- Niki kept looking for information and changed her search terms to “Pantazos” which led her to finding her great-grandparents’ marriage record and the incorrect transcription of Theodoros’ surname. If she had not kept looking, the mystery would have remained.

- Just because “this is the way it was” don’t assume that is true in your situation. I assumed that Theodoros had come to the U.S. with (or before) his children, which was the pattern for Greek men at the turn of the century. In this case, that was not the case. The mother came with the children, and the father remained in the village–a complete reversal of the norm.

Anna, Theodoros, possibly Anastasios (standing), Nikoletta, Dimitroula Pantazou, possibly Harry

[1] See Sparta Marriages 1835-1935 online at MyHeritage.com