Author: Stratis A. Solomos

published in The Faris Newsletter, Issue 73, December 2020, pages 12-16

I am most pleased to receive permission from Stratis Solomos to share his genealogy of the Solomos Family of Koumousta and Xirokampi. Stratis wrote: “Last year I was asked by the chief editor [of the Faris newsletter] to write a genealogy on the Solomos family, one of the most important families of Koumousta-Xirokambi…For practical space reasons the family tree was confined to the generation of 1960-70. By the same token, the few historical footnotes are limited to the older generations only.”

Publicizing and publishing our family history work is an unselfish and important act. It allows us to share what we learn with those who may not have the resources or abilities to conduct such research. They, too, want to know about their ancestors and connect with extended family worldwide. Thank you, Stratis, for your sharing your work with us and for providing this English translation.

The Solomos family of Laconia originates from Koumousta, a village in the Taygetos mountains, close to Sparta. In the 19th century, after the Greek War of independence, most family members moved gradually down to the flat land, to the newly founded village of Xirokampi. The origin of the Solomos family of Laconia is unclear and there is no oral tradition or myth related to the family history. In the 1950s-60s, the lawyer Georgios V. Solomos, known as “Pyrgodespotis” (Castle-Lord), was saying that he had done a bibliographic research that had allowed him to conclude that the family came from Crete in the middle of the 17th century, after the fall of Chandakas (Heraklion) in 1669 and its occupation by the Turks. More specifically, as it was narrated in the informal ‘kafenio’ gatherings, there were initially two brothers, one of whom stayed in Laconia and the other went to Zakynthos. The latter was the great-grandfather of the national poet of Greece Dionysios Solomos. Unfortunately Pyrgodespotis did not leave any written report and the above cannot be confirmed. His version may have been based only on various biographies of Dionysios Solomos.[1]

Nevertheless, the above hypothesis is not completely unfounded and can be based on the following arguments:

1) The family appears in the mountain village of Koumousta in the early 18th century, following the end of the Venetian domination over several Greek territories (and succeeded by the Ottomans).

2) It settles in an area where there are other well-known families, of established Venetian[2], Frankish and Byzantine origin. These families were living in the Laconia plains, but they moved to the mountains in 1715, when the Ottomans again conquered the Peloponnese.

3) More recent publications show that the great-grandfather of Dionysios Solomos, Nikolaos, did not go directly from Crete to Zakynthos, but to Kythira, where he married to Maria Durente[3], a woman from a “noble” family and with a large dowry. The Salamon-Solomos family, which is mentioned as important during the Venetian rule of Crete, had other members who settled in Kythira [4] and probably in the fertile Laconia, where the Venetians had provided them with arable land.

4) In addition, it was at this period that the Turks occupied Kythira for three years (1715-1718), for the island to be finally recaptured by the Venetians. It is possible that the move from Kythira to the neighboring Laconia happened at this time.

5) The wife of Elias Solomos of Koumousta (born around 1750) bears the name “Margarita”, which is not a usual name of Ottoman-occupied Greece. It is a “western” name mostly used in the Greek regions under Venetian rule.

courtesy of Stratis A. Solomos

The Solomos families of Xirokampi and Koumousta, which today number hundreds of descendants in many parts of the world, are divided into two branches which meet somewhere in the late 18th century.

The first and most numerous are the descendants of Elias Solomos. The other branch comprises the descendants of Georgakis Solomos and then Thanasis, who was nicknamed “Lales”, hence their identification as “Lalaioi” (pronounced “Lalei”). Because of this nickname there was a traditional rumor that this family branch came from “Lala” a village in northwestern Peloponnese. However, it is rather unlikely that part of the family, with the same rare surname, came to the isolated village of Koumousta from such a remote area, unless there were relatives with the already settled Solomos of Koumousta. Another rumor has it that one of them fought against the infamous Turcalbanian mercenaries “Lalaioi”.

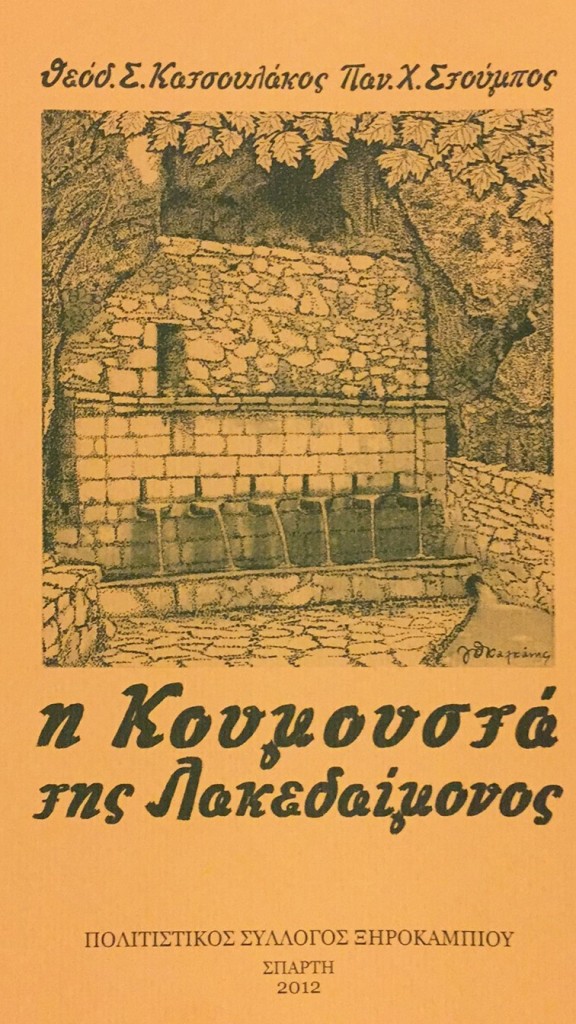

The reconstruction of the two branches of the published genealogical tree is mainly based on earlier oral reports, but also on documented, written information from the book of Th. Katsoulakos and P. Stoumpos[5]. Some evidence was also found in a report of a court dispute of a certain Meropoulis or Myropoulis, against trespassers of his property[6]. Archival research done by the genealogy research company “”ΟΙ ΡΙΖΕΣ ” (THE ROOTS) [7] was also taken into account. Another source of information was the list of immigrants passed from Ellis Island[8], as several members of the family immigrated early to America, from 1896 to 1921. The internet site of the Ellis Island Foundation has provided precious information concerning marital status, name of spouse, fellow travelers, relatives left in Greece, relatives to be met in the US, previous travels and age. From the age declared we can we conclude the year of birth, although with caution, because they often deliberately changed their age depending on the immigration laws in force. Some of these Solomos came back; for those who remained, there is the indication (USA, CAN) next to their name in the tree.

It is expected that there will be shortcomings and mistakes, especially in the tree of “Lalaioi”, which was done with more recent and less credible present-day oral testimonies. Where there is doubt, this is stated in the footnotes and the parental relationship is drawn with dashed line – – – -. Also missing are members who died in infancy or childhood. A future digitization of the registry files of Xirokampi and additional genealogical surveys could substantially help to improve this two-branch tree.

Although there is still abundant material available on the recent family members, for practical space reasons the tree was confined to the generation of 1960-70. By the same token, the few historical footnotes are limited to the older generations only. The year of birth is only mentioned for the older ancestors. Where the year of birth could not be determined exactly, it was estimated and preceded by the symbol (~). The construction of a more complete family tree that could encompass current family data and include offspring of female members would require a greater research effort and special lnformation Technology tools.

Finally, I would like to thank for their substantial contribution:

1) George P. Solomos (Italy), who decades ago recorded his first family tree version of “Elias Solomos descendants branch” and now helped significantly in the historical research.

2) Doros G. Solomos (Italy), who years ago spent time and resources on additional research for the improvement of the above mentioned family tree.

3) Dimitris “Mitsos” Ath. Solomos (Xirokampi), Nikos El. Solomos (Kalamata) and Dimitra G. Solomos-Giangos (California USA) who helped making the first, integrated version of the genealogical tree of the “Lalaioi” branch.

Stratis A. Solomos

Geneva Switzerland stratis.solomos@bluewin.ch

[1] Ν. Τωμαδάκης: Οικογένειαι Salomon-Σολωμού εν Κρήτη, Επετηρίς Εταιρείας Βυζαντινών

Σπουδών, 1938, Έτος ΙΔ’, 163-181.

[2] Σ. Α. Σολωμός: Η ετυμολογία μια τοπικής λέξης και ήθη της Γαληνοτάτης Δημοκρατίας. Φάρις-Ξηροκάμπι, τεύχος 55, Δεκέμβριος 2011.

[3] Ελένη Χάρου: Μαρία Δουρέντε, η Κυθήρια πρόγονος του Διονύσιου Σολωμού, 27 Μαρ. 2016.

[4] Μπαλτά Ευαγγελία: Η οθωμανική απογραφή των Κυθήρων 1715, Ινστιτούτο Νεοελληνικών Ερευνών ΕΙΕ, Αθήνα 2009.

[5] Θ. Κατσουλάκου και Π. Στούμπου ‘η Κουμουστά της λακεδαίμονος’, 2012.

6] ΣΥΜΒΟΛΑΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΚΕΣ ΠΡΑΞΕΙΣ του «μνήμονος Λακεδαίμονος Κυρίου Γεωργίου

ΧΑΡΤΟΥΛΑΡΗ» 1833-1835.

[7] Γραφείο αρχειακών ερευνών «ΟΙ ΡΙΖΕΣ» ( http://www.oirizes.gr ) Άρης Πουλημενάκος,

[8] Ε. Α. Σολωμός: Μετανάστες των χωριών μας που πέρασαν από το Ellis Island. Φάρις-

Ξηροκάμπι (τεύχος 50, Δεκέμβριος 2009).