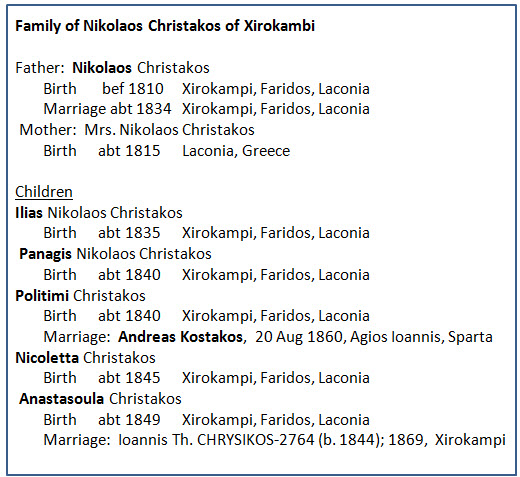

Greeks embrace an expanded definition of the term “family” to include those who marry into one’s direct ancestral line, including koumbara (godparents). I take it one step further to include anyone whose origins are from the same clan. This second post (part one here) relates stories about the relatives of my great-great grandfather, Nikolaos Christakos, as written by Mr. Katsoulakos and Mr. Stoumbos in their book, Koumousta of Lacedaimonos.

One recurring theme is the importance of the local monastery of Gola.

Monasteries were “rich” and were sources of life for the villagers. They provided steady employment for some and assistance to others. On March 1, 1828 the abbot of the monastery of Gola enumerated its holdings: vineyards and cultivated fields of berries, figs, and olive trees; cows, sheep and goats; and precious objects. People named in the Code of Gola were involved with the monastery. They may have worked as gardeners, keepers, or in the olive oil refineries, and they were paid for their labor. Monasteries often rented their land and sheep to villagers who did not have property or means to provide for themselves. The monastery also supported the local school in Koumousta; in fact, for a time during 1830, the school was located within the monastery. In the Code are these donations: October 1829-33: 81, 150 and 114 grosia (Greek for qirsh, Ottoman currency). Vyssarion Tekosis (1827-1844), an abbot in the monastery, studied in this school.

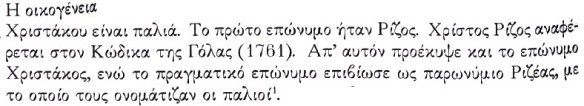

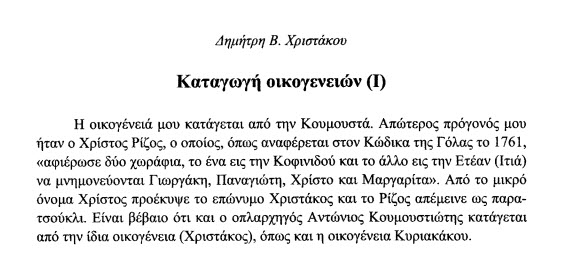

Christakos Residents of Koumousta

Panagis is the oldest Christakos named in the book. He is not mentioned further, but we can estimate that, as the father of Kyriakos who was born about 1776, he was born in the early to mid-1700’s[1].

Kyriakos, the son of Panagis, was named in the first census taken in 1830. He was referenced in the Code of Gola in the year 1806, and additional documents indicate that his involvement with the monastery of Gola was ongoing:

- On January 1, 1785, he signed a document as a witness that Christina Komni and her children sold a vineyard to the monastery for 38 grosia.

- On April 25, 1796, he signed a letter requesting assistance from the Grigorakis family of Mani after Turks destroyed the monastery of Gola.

- In 1806, he donated a field to the monastery in memory of his son, Panagis [this indicates that his son had died prior to 1806]

Thanasis is named in the Code of Gola as a laborer in the monastery, 1827-29.

Dimitris and other men from Koumousta fought in the Balkan Wars (1912-13). In the village of Koritsa (Albania) during a battle between Greeks and Turks, Dimitris was injured along with Vasilis Stoumbos, Mitsakis Mandrapilias and Christos Stoumbos. Dimitris, an artillery gun operator, totally lost his hearing and returned home, deaf. The state did not grant him a pension. His wife died, leaving him with six sons. He raised his sons and assumed the household chores of baking, cleaning, mending clothing. As the sons married and left the home, Dimitris remained alone until the end of his life.

St. B. (nickname: Kapodakis; St.B. most likely are initials for Stylianos Vasilios) died in an accident on July 21, 1943. At the end of the river Rasina is a small lake, Sgournitsa, where young men swam during hot summer days. The small cave of Komini, with green stalactites and impressive fossils, lured the bravest of them. It was there that St. B. lost his life.

Georgios is not mentioned by name but his three sons are listed in the Male Register (Mitroon Arrenon) of the Dimos (prefecture) Faridos. As such, we can estimate the birth year of Georgios as about 1845:

- Aristomenis Georgios, born 1870

- Dimitrios Georgios, born 1872

- Grigorios Georgios, born 1876

The family of Dimitrios Georgios born 1872 is enumerated in the Town Register (Dimotologion):

Christakos, Dimitris G., born 1872

Christakos, Konstantinos Dimitriou, born 1915

Christakos, Antonios Dimitriou, born 1918

Christakos, Pantelis Dimitriou, born 1920

Christakos, Panagiotis Dimitriou, born 1923

These four sons of Dimitrios were among 28 young men from Koumousta who fought during World War II. The authors wrote: The village at once became joyless [because the youth were gone.] The weather this morning was as if it was going to snow. The teacher left in the night. In the fields, no one went to work. A 10-year-old child, shocked by the events around him, listened to his mother’s voice, “Your sister is going to your uncle’s goats and you to ours” (children must now do the work since the men are off to war). From this time, the child was doomed to become a shepherd. He took bread and ran quickly to the point between the mountains. He wanted to see the men who had left to fight. He saw them when they reached Γλυστρωπές Πέτρες (slippery rocks). He shouted to tell them something he had heard early in his life, “come back victorious.” But they were far away and could not hear him.

The family of Konstandinos Dimitrios born 1915 (named above) is also in the Town Register:

Christakou, Antonia wife of Konstantinou 1922

Christakou, Pitsa (Panagiota) Konstantinou 1943

Christakos, Dimitrios Konstantinou 1946

Christakou, Stratigoula Konstantinou 1948

Christakou, Dimitra Konstantinou 1951

(Note: –ou ending denotes the feminine)

Konstandinos Dimitrios and Perikles D. are named in the School Register of 1921-22. The school archive was destroyed during the German occupation of WWII and the ensuing Civil War. Only two student lists were saved. The older list is from the school year 1921/22, indicating that there were 31 students in four classes, with the teacher Peter Dimitrakeas.

- Konstandinos Dimitrios is referenced in an incident which occurred in Koumousta during the Greek Civil War (1946-49). A skirmish arose between rebels and paramilitary forces (Xites). The Xites accused Kosta of being a communist and threatened to execute him, but the situation dissipated and he was spared.

- Konstandinos’ wife, Antonia Stavrogiannis Christakos, found the decapitated body of her brother, Dinakis, in the town square of Xirokambi (late 1940’s). There authors tell the story as follows: Dinakis Stavrogiannis lived in Paleochori. He was small in body but strong and quick. After some military operations of the army, a small stronghold of military police with help of local army men settled in the area. One night in Paliochori, Dinakis killed a military policeman who was guarding Sotiri Kakiousi and he fled. From this point, the future of Dinakis Stavrogiannis was written in black. The guards increased, and the control was extremely oppressive. In the middle of September below the Koumousta River , Dinakis fell into an ambush. Heavily injured, he tried to release a grenade but blew himself up. The next day the police cut off his head and took it into Xirokambi where they put it on public view. Among the people of Koumousta who went there to collect nuts was his sister, Antonia Christakos who in front of this disgusting view screamed, “My brother.” However, she found the courage to go to and weep at the headless body of her brother.

- Konstandinos Dimitrios and his family left Koumousta after World War II, but there is no additional information regarding their final destination. The authors explained: The war and misery that followed, along with many other social reasons, forced people from Koumousta to abandon their village and take the road abroad.

The men of Koumousta were tough. As they left their village to defend their country, their eyes were as brutal as slayers. They gathered in Megali Vrysi and departed, singing an old klepht song: How many mountains I passed, I will tell them. Mountains, don’t get snow–fields, don’t get dusty. The meaning is deep and poignant: as mean leave their village, they send a message to the mountains and the fields–may the winter not be harsh, may the fields be well watered and produce a good harvest. My family will be alone and I will not be there to take care of them.

___________

[1] Kyriakos was an adult, probably in his 30’s, when he is mentioned in the Code in 1806. Doing the math, his approximate birth year would be around 1776; if we use the estimation of 25 years to separate generations, then an approximate birth year for Panagis would be 1751 at the earliest.