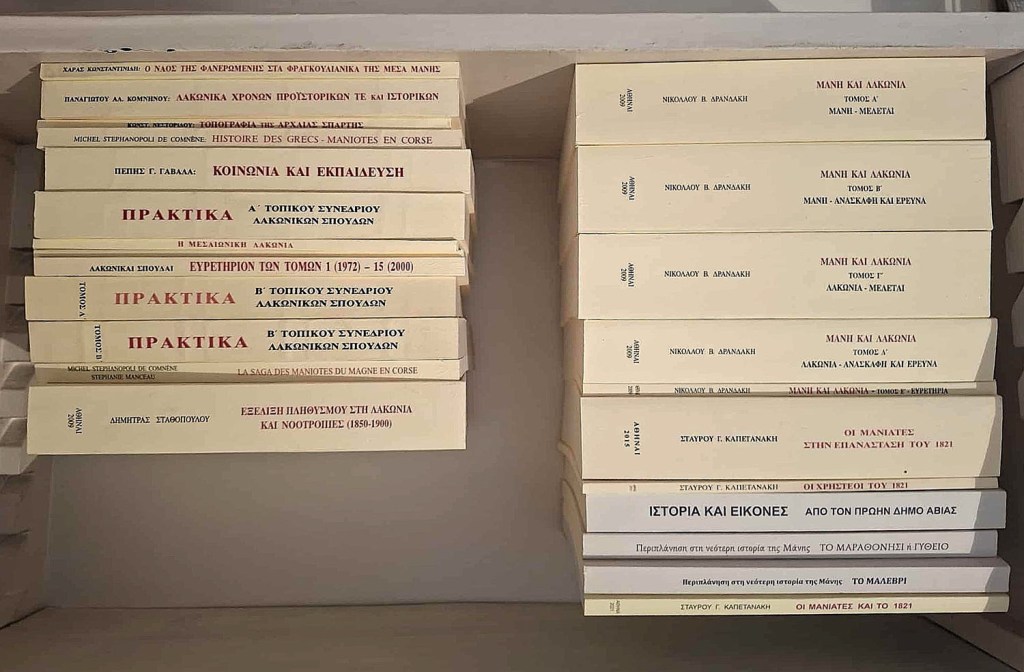

The Society of Lakonia Studies organization fulfills a vital role in documenting and preserving the history of the prefecture of Lakonia. The organization brings together historians, archaeologists, linguists, cultural specialists and other professionals who present their research at the annual conference of the organization. Their research papers are subsequently published in the Journal of Lakonia Studies, which currently consists of twenty-three volumes and numerous supplements.

This year, the organization’s annual conference will be held on December 5-7, 2025, at the Cultural Center of the Municipality of Sparta (ground floor of the Library). The theme is “Laconia 330 AD – 1830.”

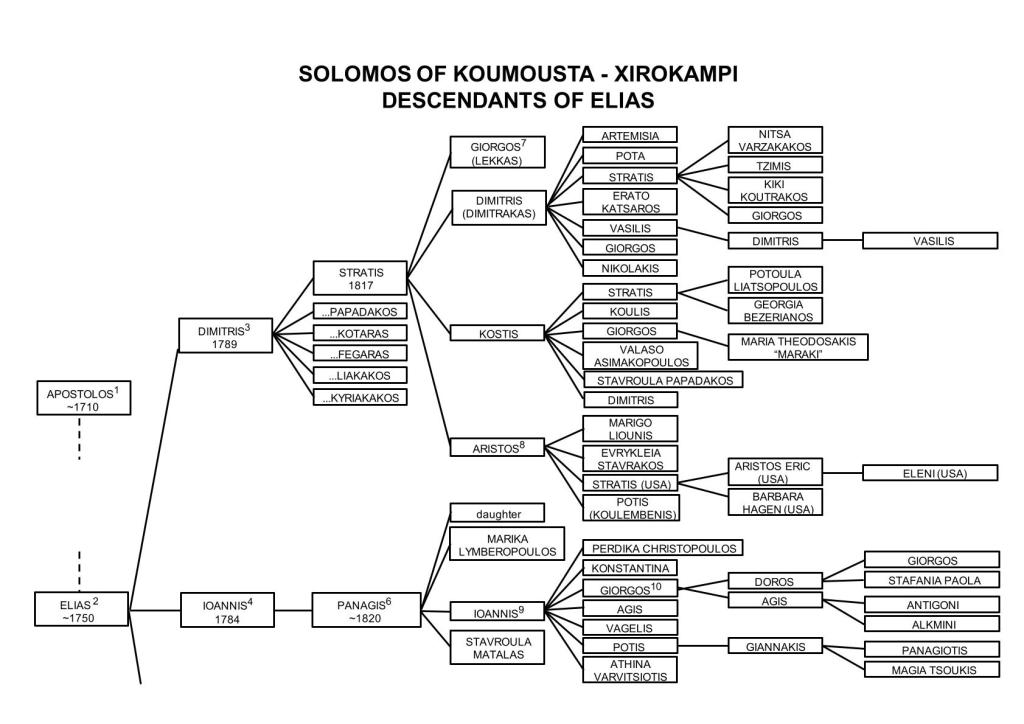

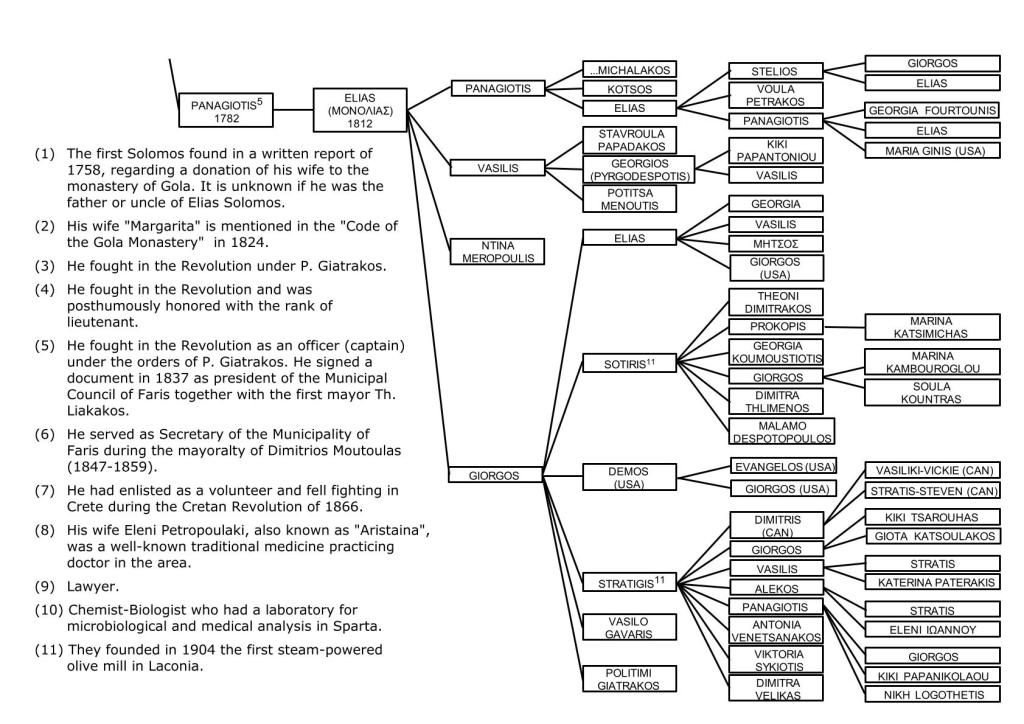

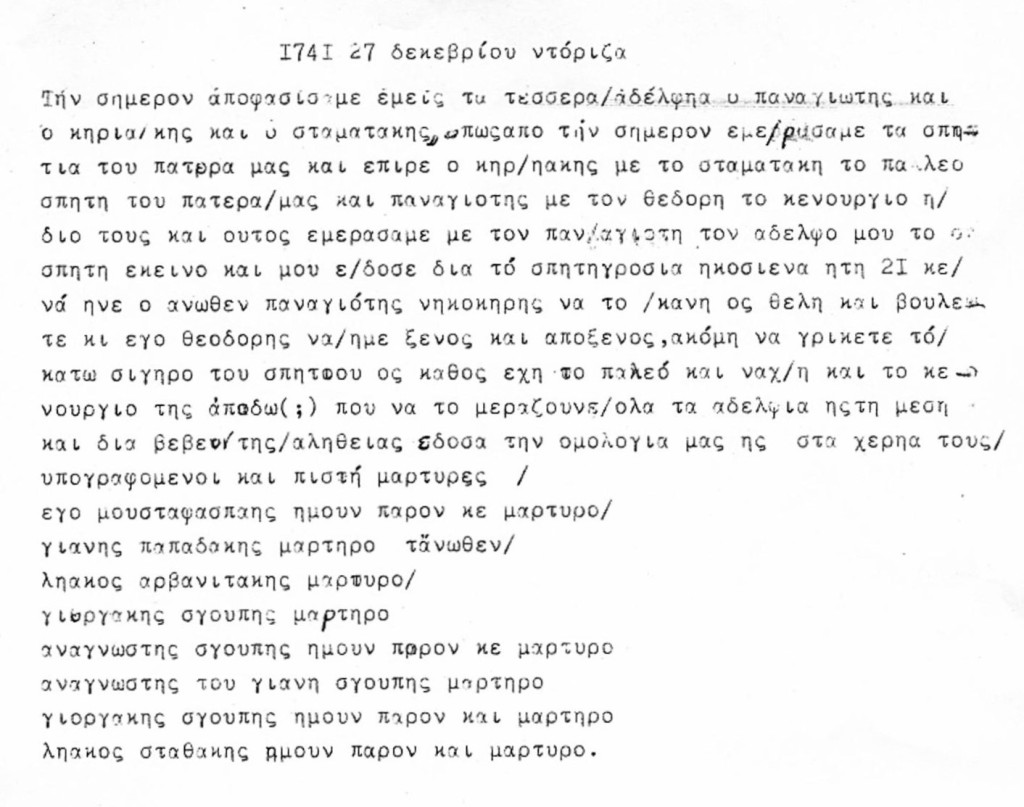

The presenters are devoted and dedicated researchers.Their goal is to educate and enlighten. Most are native to the region and work with primary source materials which may be unavailable or even unknown to outside scholars. Thus, their works extend beyond basic academics and dive into topics, people and historical elements that are less-studied and even obscure, but historically relevant and important.

This article in Lakonikos.gr outlines (in Greek) the program and speakers. My very rough computer-assisted translation of the program follows:

Friday, December 5

Opening Session (18.00-20.00) | Chair: Socrates Kougeas

18.00-18.30: Arrival

18.30-19.00: Welcome

19.30-19.15: Dimosthenes Stratigopoulos, Nikiphoros Moschopoulos, president of Lacedaemonia (ca. 1288 – ca.1315), and leader in Mystras

19.15-19.30: Dimitrios Th. Katsoulakos, Surnames with Byzantine origin in the villages of Faridos

19.150-19.30: Stavros G. Kapetanakis, Ibrahim’s unsuccessful attempt in 1826 to subjugate the Maniots and its long-term consequences

19.30-20.00: Discussion

Saturday, December 6

First morning session (9.30-11.00) | Chair: Dimitrios Vachaviolos

9.30-9.45: Danae Charalambous, The surviving frescoes of the church of Panagia Krissa in Finiki, Laconia

9.45-10.00: Sofia F. Menenakou, The brushwork of the painters Anagnostis from Lagkada and Nikolaos from Nomitsi in the Church of Saint George in Panitsa (Laconian Mani, 18th century)

10.00-10.15: Leonidas Souchleris, The northern part of the Eurotas valley in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. Residential perspective: urban planning, cemeteries and road network.

10.15-10.30: Georgios P. Kountouris, Monuments of the Early Christian Period in Voies

10.30-10.45: Panagiotis D. Christofilakos, The Byzantine church of Saint Athanasius in Paleochori, Lakedaemon

10.45-11.00: Panagiotis S. Katsafados, Following the traces of icon painters in Mani during the post-Frankish period

11.00-11.30: Break

Second morning session (11.30-13.00) | Chair: Dimosthenis Stratigopoulos

11.30-11.45: Panagiota D. Laskaris, The Laskari clan in Lacedaemon. The biographical stories of Demetrios Laskaris as a starting point for an existential historical investigation

11.45-12.00: Christina Vambouri, Highlighting the history of Byzantine Laconia through the newspaper Embros during the first half of the 20th century

12.00-12.15: Dimitrios S. Georgakopoulos, New information about the founder/donor of Panagia Chrysafistissa

12.15-12.30: Michael Grünbart , An empire vanishes – imperial concepts vs. political reality in late Byzantium

12.30-13.00: Discussion

First afternoon session (17.00-19.00) | Chair: Georgios Kountouris

17.00-17.15: Eleftherios P. Alexakis, Byzantine pronoiai, Venetian captaincies, and the development of the political system of Outer Mani

17.15-17.30: Antonis Mastrapas, Searching for ancient Sparta in the 18th and 19th centuries

17.30-17.45: George V. Nikolaou, Laconia through the work of the English traveler William Leake, envoy of the English government (early 19th century)

17.45-18.00: Kyrillos Nikolaou, Laconia through the second travelogue of the French consul and traveler François Pouqueville (early 19th century)

18.00-18.15: Panagiotis N. Xintaras, Laconian place-names through the pen of French travelers

18.15-18.30: Alexandros Gizelis, Sparta in the political literature of Protestantism during the era of the Religious Wars (16th-17th century)

18.30-19.00: Break

Second afternoon session (19.00-20.30) | Chair: Yannis Tsoulogiannis

19.00-19.15: Yianna Katsougraki, At the end of the thread: from the material to the immaterial. The presence of weaving in Byzantine and modern Laconia

19.15-19.30: Michalis Sovolos, Indexing the first decisions of the Court of First Instance of Sparta: Persons and matters concerning Mani, 1770-1821

19.30-19.45: Georgios A. Tsoutsos, Enlightenment and Ancient Sparta: The case of Gabriel Bonnot de Mably (1709-1785)

19.45-20.00: Dimitrios Galaris, Nikitas Nifakis: the author of the Declaration to the European Courts at the liberation of Kalamata from Ottoman rule

20.00-20.30: Discussion

Sunday, December 7

9.30-10.30: Guided tour of the Archaeological Museum of Sparta

Morning session (11.00-12.30) | Chair: Georgios Nikolaou

11.00-11.15: Marios Athanasopoulos, “In this sacred Struggle, I too, taking up arms in my hands, ran to all the battles of my most beloved homeland…”: The life and deeds of the 1821 fighter, Father Polyzois Koutoumanos

11.15-11.30: Dimitrios Mariolis, Dimitrios Poulikakos. Military leader of 1821 from Vamvaka, Mani

11.30-11.45: Socrates V. Kougeas, Mosaics of the life and actions of the legendary figure Zacharias Barbitsiotis – The actions of the chieftain Sousanis

11.45-12.00: Giannis Michalakakos, Ilias Bispinis, a forgotten fighter of 1821 from Laconia

12.00-12.15: George – Konstantinos K. Piliouras, The Holocaust at the Paleomonastiro of Vrontama

12.15-12.45: Discussion

Afternoon session (17.00-19.00) | Chair: Dimitrios Katsoulakos

17.00-17.15: Pepi Gavala, Court of First Instance of Laconia – Correspondence Register: Transactions and Cases (February-April 1830)

17.15-17.30: Yannis N. Tsoulogiannis, The action of Panagiotis Krevvatas through two letters

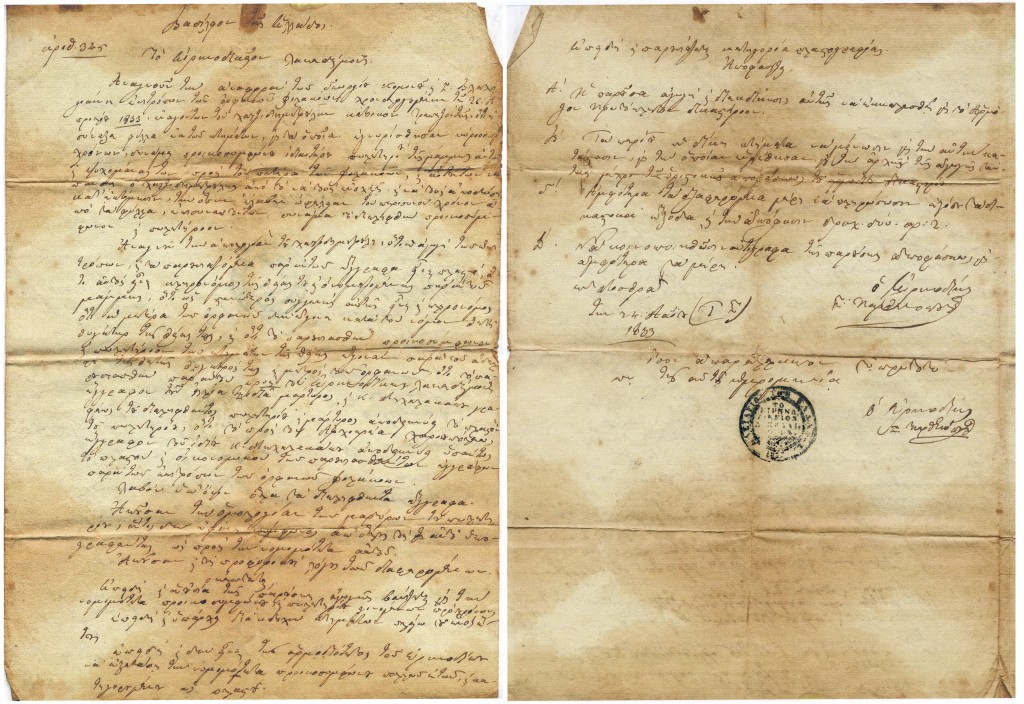

17.30-17.45: Dimitrios Th. Vachaviolos – Stylianos D. Dimitropoulos – Dimitrios Ath. Christou, Two unknown documents from the Museum of Ecclesiastical Art of the Holy Monastery of Monemvasia and Sparta concerning Bishop Kyrillos Germos of Karyoupolis († July 1842)

18.00-18.15: Nikos I. Karmoiris, Papa-Kalomoiris, the Levite (cleric) chieftain from Vordonia

18.15-18.30: Katerina Diakoumopoulou – Maria Giatrakou, “ For Giatrakos’ great struggles.’ The monumental speeches in Parliament and the indirect references in the dramaturgy of M. Chourmouzis.

18.30-19.00: Discussion

End of the conference proceedings

These papers will be published in the next issue of the Journal. If there is an essay of interest to you, contact the Lakonia Studies organization at: etlasp@gmail.com. This pdf document lists the Table of Contents for each of the twenty-three volumes of Lakonia Studies, prior to this 2025 conference. Volume(s) can be purchased from the Lakonia Studies organization for 20 euros per book.

The work of this organization and its members is important, and must be accessible to people worldwide. I have written previously about bringing the Journal of Lakonian Studies to the Library of Congress, first in 2024 and this year in 2025. Let’s spread the word together and introduce the world to our modern-day Spartan intelligentsia!