by Panagiota / Tania G. Kalkanis – Argyris

published in The Faris Newsletter, Issue #77, December 2022, page 12

Two articles published in our journal concern the medical practices that were applied and pharmaceutical means available to our compatriots in the past. Specifically, they refer to the era of the great uprising of 1821 and the time of the 1918 flu (see Stavros Th. Kalkanis, “Empirical doctors and medical practices in our region – and elsewhere – in ’21”, Faris 68 (2018) 3-6, and “The Spanish flu of 1918 as experienced (?) by a family in Goranoi”, Faris 73 (2020) 5-8.

Injuries in 1821 were treated with amputations and improvised poultices, while the 1918 flu, which wiped out entire families in our villages, was dealt with by our compatriots (and the entire world) with a little quinine and whitewashing of houses.

Similar was the treatment of the problems that our compatriots had with their teeth up to the middle of the past century. They used improvised “remedies” (or concoctions), which were essentially herbal remedies from the region. Unfortunately, these dealt with pain and other dental problems in a rudimentary way. They usually resulted in painful tooth extractions.

Our compatriots of today – especially the young – do not know or can hardly imagine the conditions, the means and possibilities of treatment but also the usual outcome of dental problems until the beginning of – at least – the past century.

Medicines and extractions were usually applied or carried out by elderly village women, and men or women who had the reputation of experienced and skilled “specialists”. They were the so-called “good doctors” of the teeth or “kompogiannites”, in other words empirical doctors who lacked the primary knowledge and the tools or materials available today.

The herbs (or botanicals or drugs) were placed on the gums of the aching tooth (after being crushed in oil or dried and ground into powder) or were soaked in water for days (compresses) or dissolved in boiling water (extracts) or in alcohol (tincture)…

With these, they made gargles, pads, or compresses, but some were swallowed (pills). Almost always, however, they started with tsipouro and olive oil, which they gargled for a long time to alleviate the pain. When the tsipouro was swallowed, it naturally acted as a “dizzying” substance… However, there was always the question – and the concern – of dosage or possible toxicity.

We have gathered information and memories from our wider region and documented the most common herbal remedies from our land, as well as their common uses and actions. Some of these were:

• anise (as powder or toothpaste or by chewing seeds, as decoction, extract, compress, essential oil, …for loose teeth and gums, tonic), lavender (as a decoction for toothache relief or as a tooth fixative…), orange (as an oil for calming effect / relaxation…)

• nettle (crushed, dried or boiled as a compress or wash and as a decoction to stop bleeding of the gums…), honeysuckle (as an ointment or poultice or gargle against toothache but also as a remedy for bad breath…), mulberry (as a thick decoction of its leaves for gargle against tooth and gum pain…)

• cloves -mainly, thyme, ginger, and marjoram (as a toothpaste, as a powder or mashed ointment for compresses, as crushed oil, as infusions or extracts…against tooth pain and breath freshening,… and as antiseptic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory…)

• mint, spearmint, and pennyroyal-which are related plants- (as ointments in compresses and poultices, as extracts and essences, oils, patches of their fresh leaves…, for aroma, antiseptics…)

The women from our villages usually undertook the collection, processing, and administering of the above-mentioned medicines. The names of most of the men or women in our area who had these capabilities have unfortunately been lost or are only maintained in the memory of their family members. With this note, we preserve the name of Stavroula Sourtzi (née Stratakou, originating from Goranoi) who died bedridden in Xirokampi. Her daughter, Ourania Panteli Frangi, who lived in Xirokampi (and her later years in Canada), has narrated and written that many who collected some of the herbs we mentioned would give them to her mother for processing.

However, even then – and now for those who still use them – special attention should (and must be) paid to their dosage or toxicity. Especially today with the existence of sprays and pesticides. Herbs are not a panacea.

Rarely in the past did our compatriots take care of their teeth as long as they did not have problems. One of the practices they used to take care of them was chewing the ends of thin twigs, or roots of some of the plants mentioned above, that were easy to find. By chewing these, they created tassels that facilitated cleaning the teeth and prevented plaque buildup.

A more drastic method was the use of improvised “toothbrushes” with long handles (also called “tooth-rubbers”). They were made from animal hair (mainly from pig bristles), and with these, they rubbed the teeth, applying powders or paste / ointment or oil from some of the above-mentioned herbs (such as chamomile, ginger, clove, or mint…).

When the medicines were not effective or sufficient for treating dental problems and pain from bleeding, then skilled or simply calm old women usually took further action, which was the only way. Extraction of the tooth. Many resorted to the “good doctors” or “kombogiannites” who were villagers or wanderers. They were called “good doctors” because they referred to themselves and advertised as such, and they were also called “kombogiannites” because they used to keep their medical remedies secret, wrapped in handkerchiefs tied in knots (“kompoi”). Many of them were simply skilled individuals who also practiced the profession of barber, or even specializing in bloodletting with leeches collected from stagnant waters.

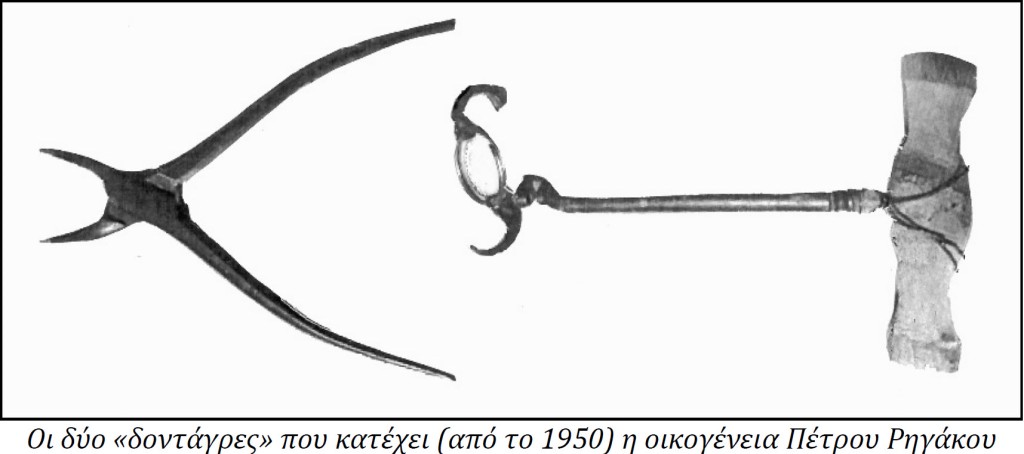

Many tooth specialists had special pincers (called “tooth forceps” or “dental pliers”) for extracting teeth. It is known that sometimes they missed and extracted (instead of the painful tooth) another nearby tooth or teeth. These pliers were passed down from generation to generation in the families who owned them. Two of these pliers are saved by the family of Petros Stavros Rigakos (see photo). These were brought to Goranoi from America (around 1950) by the mother of Georgios K. Rigakos (or Stavrakos), Stavroula (nee Kyriakakou). “During those years, these pliers relieved many Goranites by removing their damaged teeth…” notes Aimilia P. Rigakou.

We record, finally, one of the many superstitions of the inhabitants of our village who attributed the falling out of teeth to the fact that some sufferers had their mouths open while a number of pine caterpillars crawled on the ground in front of them.

We also record one of the many scams that were attempted at that time. In the 1950s, glass bottles or jars – called “yalakia” or “gyalakia” – containing, according to labels, “tooth tonic” were circulated and sold in the cities of Athens and Patras. This was advertised “as the only healing medicine that relieves pain and protects teeth from any possible disease…”. These jars, according to testimonies of older people, had even reached our villages.

All these remedies, practices, and quack doctors ended or, at least, slowly disappeared (?) when the first dentists graduated from the University and settled in our area.

But let this note be a memorial for those well-intentioned “doctors” whose purpose was to ease pain and heal the sick.

I (Carol Kostakos Petranek) am honored to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the fourteenth article of the ongoing series. Previous articles can be viewed here.

A fascinating article about medicines and health during earlier times! A similar topic, is a book called the Dangerous Hour, and another called Health and Healing in Rural Greece by Richard and Eva Blum. These books go into the effects of the moon and sun and monthly and annual cycles when herbs should be gathered, the trusted practitioner that is more highly regarded than a modern educated physician, and so much more.

But to discover this from your ancestry’s roots is especially ‘gold’!