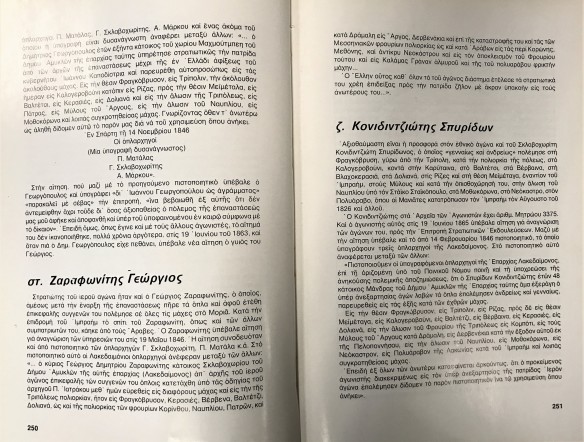

When a family moves from one village to another, the natives of their new “horio” may refer to them as the people from [name of their former village]. That is exactly what happened to my third great-grandfather, Panagiotis Zarafonitis. Sometime in the mid-1800s, he left his mountain village of Zarafona and settled in the fertile plains of Sparta, specifically the village of Sklavochori (now part of Amykles).

He became known as Zarafonitis, the man from Zarafona. His original surname is unknown. The Zarafonitis family of Amykles claims that there were two Zarafona families who settled in Amykles: Mazis and Tountas. Another comment was that the Maltezos family of Zarafona also came to Amykles. Because the migration most likely occurred after the Revolution of 1821 ended, around 1830–before records were created by the modern Greek state–the name will have to remain a mystery.

Zarafona, also known as Kallithea, is most likely ancient and surely pre-dates Byzantium. Its church, Enniamera tis Panagias / Εννιάμερα της Παναγίας (Nine Days of the Virgin Mary) was built in the 10th century.

The village has a castle which towers at the top of a mountain. “According to an inscription found on the west external wall, the castle was constructed in the period that the Despotate of Moreas was governed by Theodoros II Paleologos (1407-1448). Therefore it was a construction of the first half of the 15th century, part of the effort of the Byzantines to confront the Ottoman threat.”1 The short video below shows both the castle and the surrounding countryside.

With the castle as a fortress, one can conclude that the Zarafonites were activey engaged in thwarting the Ottoman incursion into their territory. It’s rather thrilling to imagine Panagiotis Zarafonitis and others in active opposition to this threat, and their jubilation when the Ottomans were defeated.

It makes sense that, after their freedom was secured, Panagiotis did exactly as so many others — go down from the mountain to settle in the fertile valley.2 I know he was there by 1849, the approximate year of the birth of my second great grandmother, Giannoula, in Sklavochori.3

Zarafona is an agricultural community. Crops such as olives, citrus fruits, vegetables, and grapes are cultivated. The region has a long history of wine production. The village is peaceful and the neat gardens and livestock give it a homey atmosphere.

Left: Major donors for drilling, 1995; Panagiotis P. Ferizis; Ilias Legakis

Right: Gift from the Zarafona Women’s Syllogos and Leonida Nikia, 1-5-2013

1912-1940: S.K. Voudouris; P I. Ferizis ;I. D. Chrysikos; I. V. Maltezos; P. G. Maltezos; G. N. Voudouris; I. P. Giakas; P. Ch. Farlekas; K. D. Stamatopoulos; N. Th. Oikonomopoulos; I. H. Douvris; Ef. Lochagos; N. G. Ferizis; S. P. Maltezos; P. V. Flogos; I. P. Manousopoulos

1940-1949: P. D. Karakitsos; G. I. Plagakis; Chr. P. Katranis; D. I. Nikias; E. P. Oikonomopoulos; P. G. Danas; I. G. Koumoutzis; G. Th. Vlachos; I. P. Oikonomakis; H. I. Danas

I thank Yanni Lambrinakos for taking me to see this village. His knowledge of the area and its people have helped me better understand this branch of my ancestral roots.

1Source: Kastrologos

2For migration patterns after the Revolution, see this post.

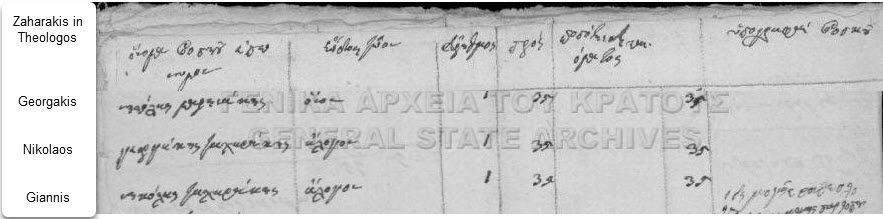

3Giannoula’s marriage record to Dimitrios Nikolaos Zacharakis on April 18, 1869 states her residence as Sklavochori. I estimate her birth at 20 years prior to marriage.

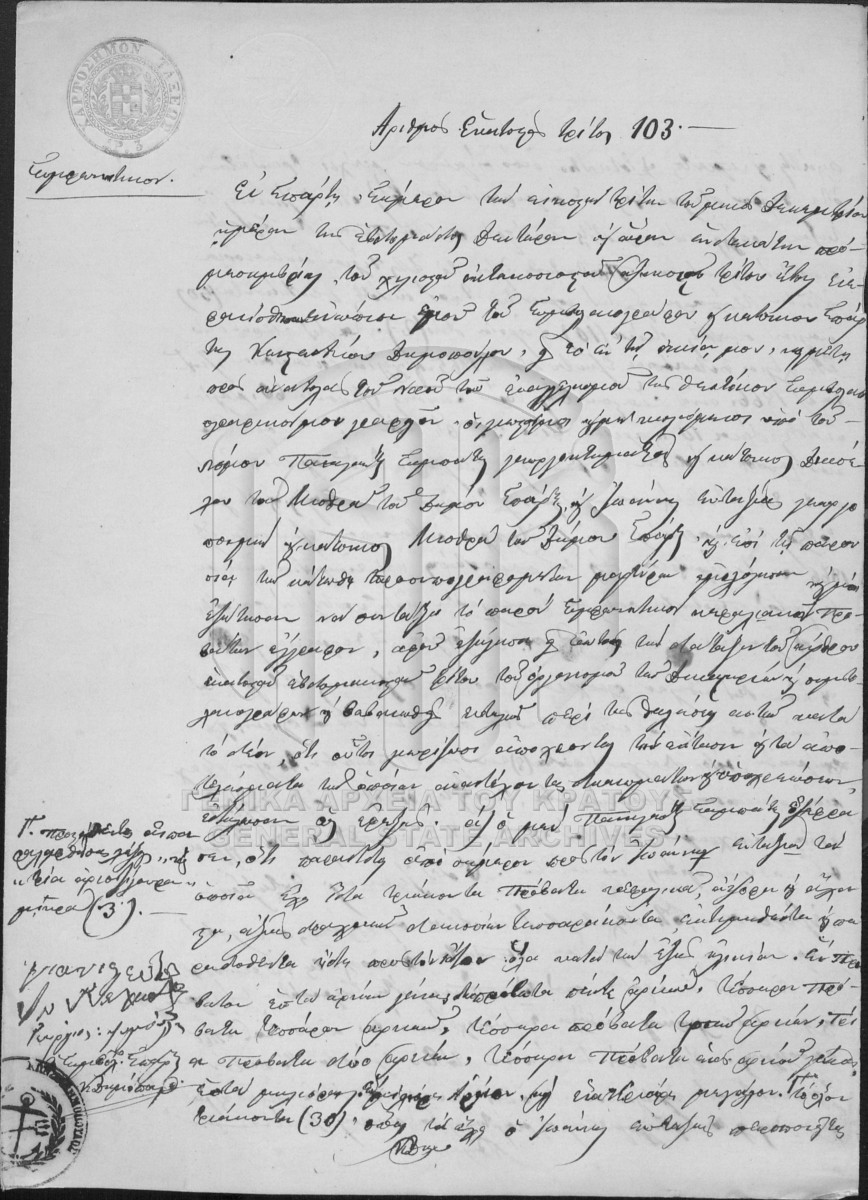

Metropolis of Sparta, Marriage Index Book

Book: Sparta, 1866-1872; Year: 1869; Entries: 88-94

Entry #89

License Date: April 18, 1869

Marriage Date: not given

Groom: Dimitrios Zacharakis, no father listed; residence: Theologos

Bride: Giannoula Zarafonitou; father: P., residence: Sklavochori

Church Name: not given

First marriage for both bride and groom

Photographed at the Metropolis of Sparta in Sparta, Greece by Carol Kostakos Petranek, July 2017