by Georgiou V. Nikolaou

published in The Faris Newsletter December 2007, Issue 44, pages 3-5

The conquest of the Peloponnese by the Venetians (in 1685/87) had very serious consequences for its inhabitants, both for Christians and for Muslims. One of these was the Christianization of about 4,000 Muslims, mainly in the regions of Gastouni and Mystras, where the presence of the Turkish-Muslim element was more intense than in any other region of the Peloponnese, during the period of the first Turkish rule. The Venetian officials in their reports do not agree among themselves on the assessment of the causes that led to these mass conversions to Christianity: some, such as the ledger keepers Griti and Mikiel, argue that those who became Christians had Christian ancestors, who had previously converted to Islam and found the opportunity, after the expulsion of the Turks, to return to their previous faith or to the faith of their ancestors, while others, such as the Proveditor Fr. Grimani, believe that the motives that drove these individuals to become Christians were fear for their lives and self-interest. Undoubtedly, both views have a dose of truth. However, the absence of testimonies from Ottoman sources (which either have been destroyed or still remain unpublished) does not allow us to see exactly what extent individual or mass conversions to Islam had taken in the Peloponnese during the first Turkish rule, so that we can speak with more certainty about the possible relationship between these two opposite religious conversions (Islamization and Christianization).¹

http:/www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/391071

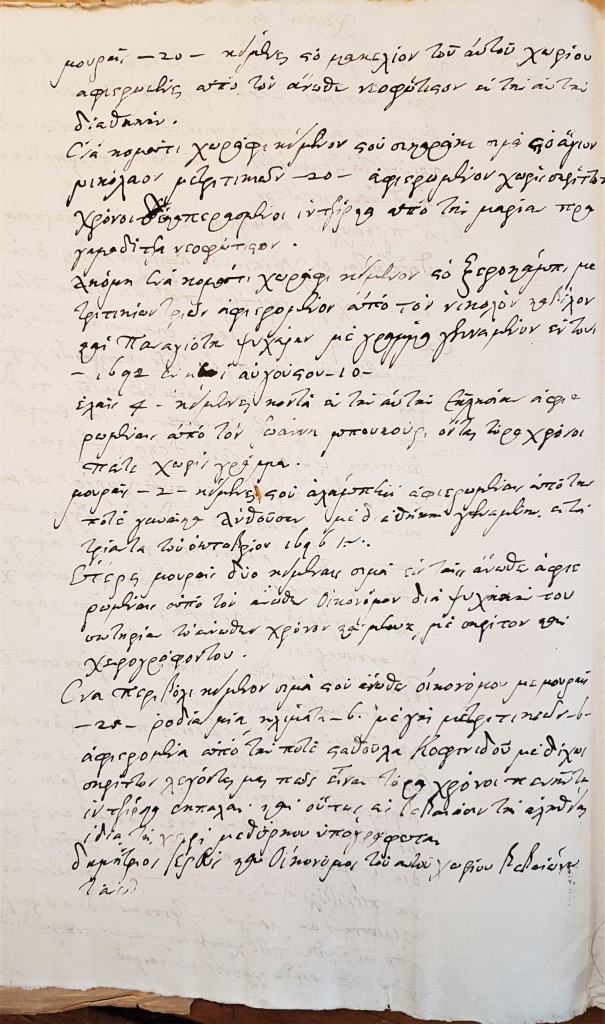

For the Christianizations in Mystras and in villages of this kaza, we are given information by documents from Venetian archives that were published two decades ago², as well as others that remain unpublished. Specifically, according to this important archival evidence, Christianizations are recorded in Mystras and in the villages of Agios Ioannis, Sklavochori, Arkasas, L(i)opesi, Floka, Kastri and Voaria (?). According to this source, in the settlement of Arkasas or Arkasades, which is known from Byzantine and post-Byzantine sources, ³ the following seven families were Christianized at the beginning of the Venetian conquest:

Village of Arkasa

- Michalakis Messinakis, 30 years old his wife, Dimitris his son, Georgoula his sister-in-law.

- Panagiotis Gorianitis, 30 years old, his wife Stathou, his mother, a son, 6 months old, Dimitrios, his adopted son.

- Panagiota Safitsa daughter of Kanella, Dimitris, her adopted son

- Nikolaos Silikanos 25 years old, his wife Gkolfo, his mother.

- Thodorakis Karfopoulos 30 years old, from Rizia (?), his wife, Ilias his father, Panagiota, his daughter.

- Pieros Maniatis from Kastania 22 years old, his wife, Nikolaos his son, Maroula, his adopted daughter.

- Panagiotis Tzourakis, Panagiota Flokiotissa his wife, Dimitris, his son.⁴

Specifically, 25 people were Christianized (13 men and 12 women), who, as we see, are mentioned by name, and with their exact family relationship, some even with their age. Although we do not know the population of this settlement before 1685, we can, judging by the data from the Venetian census of 1700 (38 families/145 people) ⁵, conclude that a significant number of inhabitants converted to Christianity. It appears, in fact, that two of these families had recently or previously settled in Arkasa: Panagiotis Gorianitis from Goranous, and Pieros Maniatis from Kastania of Mani. This record, which is important from the perspective of the composition and size of the families of this settlement in a period where such information is scarce, shows, indirectly, that in this village – as in other neighboring villages – several Muslims lived before 1685. However, since, as we said, we do not have at our disposal reliable testimonies from Ottoman archives, we cannot determine with certainty whether they were genuine Turks – Muslims or Islamized Christians, as is suggested in other sources.

The historian Peter Topping argued that the fact that the individuals who were Christianized then in the Peloponnese bore Greek surnames (as here) shows that they had Greek ancestors, a hypothesis that is repeated by other historians. This argument is very strong, but not absolutely certain. Perhaps these individuals changed, with their Christianization, not only their baptismal name, but simultaneously also their family name, something which happened in certain cases, as other Venetian sources inform us. Unfortunately, the type of records does not help us to give a more certain answer to this very important question. Only the systematic research of the unpublished documents that contain other names of Christianized people from Laconia, with more data, will better illuminate this issue. This is at least what our studies show for other regions of the Peloponnese, regarding the above topic. Moreover, this brief record does not help us at all to answer with certainty whether these individuals were Christianized by baptism – a fact that would lead us to the conclusion that they were genuine Turks/Muslims, given that, according to the sacred canons of the Orthodox Church, baptism is a non-repeatable sacrament – or if they simply received the holy unction as was done then in similar cases, precisely because they were Christians who had converted to Islam and returned to their original faith.

Whatever happened, one thing is certain. These people who lived during the brief period of Venetian rule (1685/87-1715) as Christians, found themselves in a difficult position in 1715, with the reconquest of the Peloponnese by the Ottoman Turks. According to completely reliable testimonies, all the Christianized people of the region of Mystras – in contrast to those of the region of Gastouni – were executed because they were considered murtads, which means, deniers of their faith. They had committed, that is, the gravest sin, according to Islamic law⁶. Thus, would close, at least for some of these individuals, the cycle of successive conversions from the last decades of the 17th century until 1715, which passed through the following phases: original Christian descent – Islamization – conversion to Christianity and again Islamization at the beginning of the second Ottoman rule.

___

¹ See on this issue Georgios V. Nikolaou, Islamizations in the Peloponnese from the middle of the 17th century until 1821, ed. Herodotos, Athens 2006, p. 37-42, where the relevant sources and bibliography.

² Konstantinos Mertzios – Thomas Papadopoulos, “Mystras and its region in the Archives of Venice during the Venetocracy (1687-1715)”, Lakonian Studies, vol. 19th (1988), p. 271-275, document from Mystras dated September 20, 1689.

³ See Theodoros S. Katsoulakos, “Sales documents of the 18th century”, Faris, issue 14 (1996), p. 5, Dimitrios K. Giannakopoulos, “The travels of the Italian Ciriaco de Pizzicoli in late Byzantine Laconia”, Faris, issue 32 (2002), p. 13, where this settlement is identified with the ancient Pharida.

⁴ K. Mertzios – Th. Papadopoulos, op. cit., p. 274.

⁵ Vasilis Panagiotopoulos, Population and settlements of the Peloponnese, 13th-18th Centuries, Athens 1985, p. 284.

⁶See G.V. Nikolaou, op. cit., p. 49-52.

I (Carol Kostakos Petranek) am honored to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the twenty-first article of the ongoing series. Previous articles can be viewed here.