At the bottom of a wooden trunk, beneath piles of dusty documents, lay long-forgotten papers unlocking the history of the Konstantarogiannis family of Toriza, Lakonia. Countless years ago, the trunk was procured by an unknown ancestor and placed in the family home. It was a handy repository for documents, certificates, and military papers. But for dozens of years, its cluttered contents remained untouched, unexplored and unexamined.

As a young lad, George Konstas worked the potato fields of Taygetos with his father, Pericles. While they planted and plowed, Pericles told George of their family—its origins, its people, its struggles.

Pericles Konstantarogiannis working his potato fields in the Taygetos mountains.

George heard the story of four brothers named Theodoros, Stamatakis, Kyriakos, and Pangiotis who, after Ibrahim’s invasion of the Peloponnese, left their mountain village of Manari, Gortynias, Arkadia and settled in equally mountainous Toriza, 10 kilometers from Xirokampi. Panagiotis was George’s forefather.

Pericles told George of ancestors who supported the 1770 Orloff Revolt, part of Russian Empress Catherine the Great’s failed “Greek Plan” and precursor to the Greek War of Independence. “My father knew these stories, but he never told me that we had documents explaining the family roots,” George related. “He probably hid the documents from previous family members. And sometimes my father confused the events because he had heard the stories handed down from his parents and relatives.”

George was taught by others, as well. “In the evenings, the older people told stories,” he recalled. “We had no electricity, no television, no entertainment, so they talked and I listened. But I thought these were myths, not true facts.”

Despite his skepticism, George was fascinated by his family’s history. As an adult, he began to record all the tales heard during his lifetime. As he wrote, his interest escalated into a passion to preserve what he had been told. He knew that if he did not do so, the history of his family would be forever lost.

When George’s daughter chose to marry in Toriza in 2007, the extended family returned to their village. Coming from America and Canada, they gathered at their childhood home which by then had been willed to them by their parents.

Konstantarogiannis (Konstas) siblings in front of the “old” family home, 2007

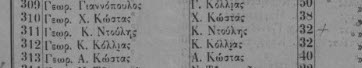

The siblings deliberated its disposition. Nobody wanted to sell it, but taxes needed to be paid and other matters settled. George decided to buy his brothers’ shares and he became the sole owner. As people wandered through its rooms, taking items for keepsakes, the wooden trunk was rediscovered. Opening its lid, George found a jumbled mix of papers, many stained and dirty. Too overwhelmed to examine them there, George packed and took the contents to his house in Virginia.

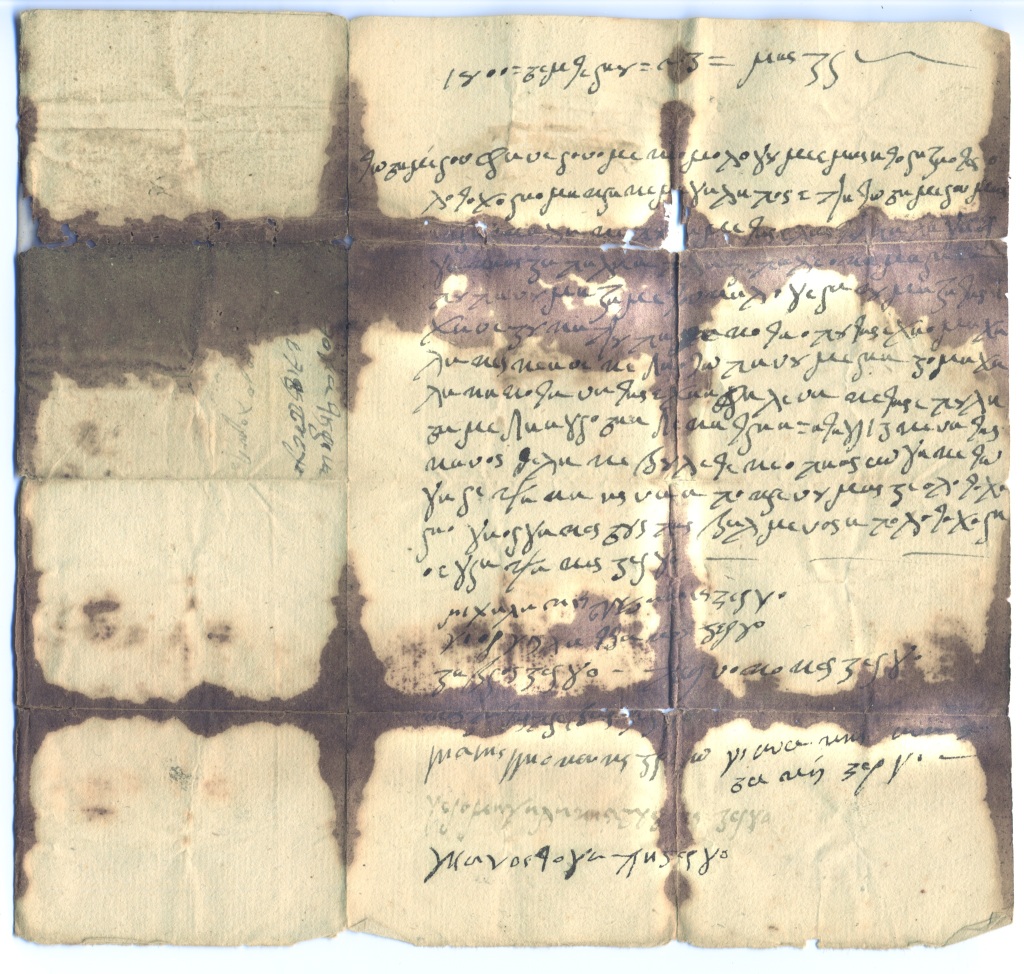

Many of the documents were in almost irreparable condition: torn, water stained, faded, moldy. As he sorted through them, George found a wallet. Folded inside was a disintegrated envelope inscribed with the words, OLD DOCUMENTS BEFORE 1819. He was astounded when he extracted yellowed, crinkled papers dated 1800, 1812, 1819 and 1833. And one dated 1741!

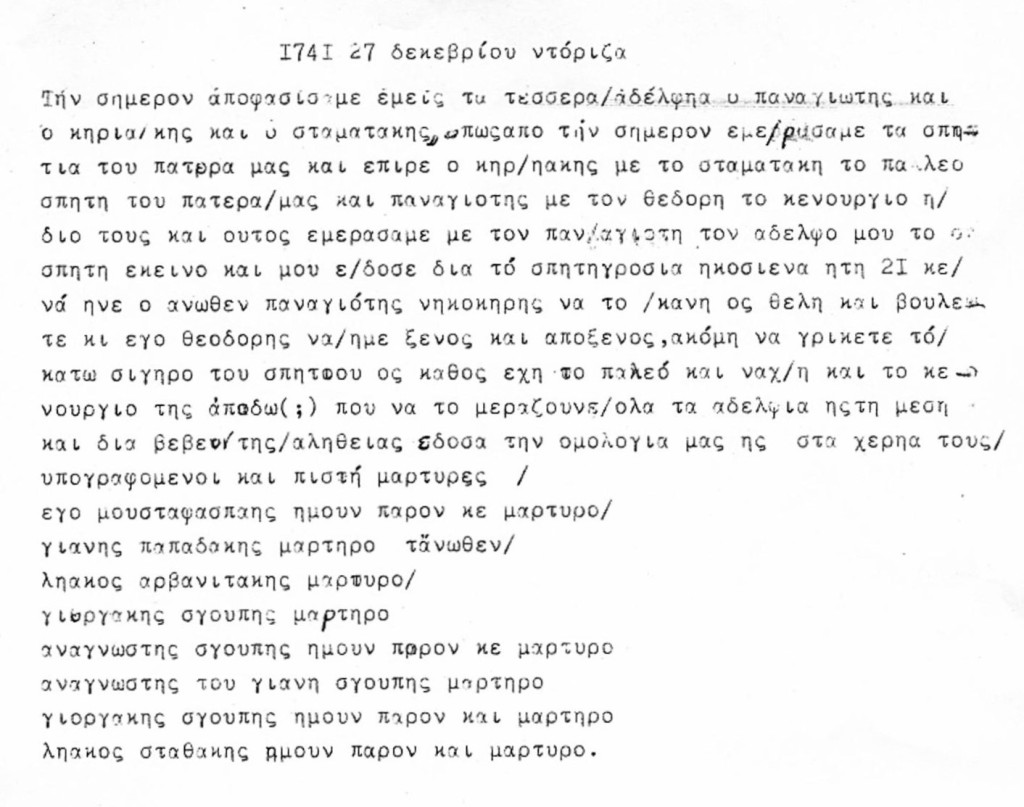

This document dated 27 December 1741 reveals the names of the four brothers– Theodorakis, Panagiotis, Stamatakis, and Kyriakos–who received an inheritance from their father and split up their fortune. They were from Manari and came to Toriza. This is the exact story George’s father described. It was not a myth; it was true.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

1741 27 December Ntoriza (Doriza)

Today we decided the four brothers, Panagiotis and Theodoris and Kyriakis and

Stamatakis, that from today we have split the houses of our father and Kyriakis and

Stamatakis took our father’s old house and Panagiotis and Theodoris took our father’s

new house the two of them and truly split with my brother Panagioti that house and he

gave me for my half, grosia twenty-one (ie 21) and so the aforementioned Panagiotis is

the owner to do as he pleases and I, Theodoris will be a stranger and estranged, also to

designate the bottom floors of the house just as the old house has so to the new house

over here; where we split, all the brothers, down the middle. And for the certified truth

we gave our word onto the signatures of these trusted witnesses.

I, Mustafaspaïs (Mustafa-Sipahi was a feudal cavalryman), was present and witnessed

it

Giannis Papadakis witnessed everything above

Liakos Arvanitakis witnessed it

Giorgiakis Sgoupis witnessed it

Anagnostes (Church reader) Sgoupis I was present and witnessed it

Anagnostes (Church reader) of Gianni Sgoupis witnessed it (the writer of this document)

Giorgiakis Sgoupis I was present and witnessed it

Liakos Stathakis I was present and witnessed it

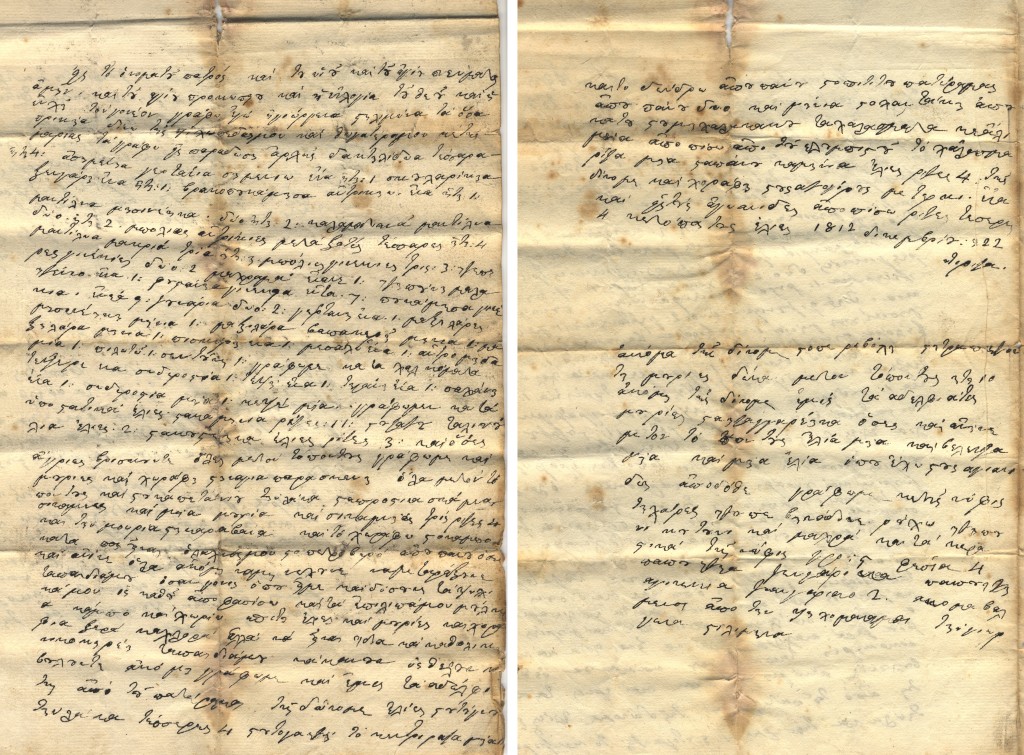

Above each image is a description of the documents from the early 1800’s:

1800 September – Lease agreement signed at Mystra for the Koumpari Monastery lands:

1812 December 22 – exhaustive dowry list of Georgina Stilimina for her adopted daughter/grandaughter, Maria:

1819 January 15 – An agreement between the villagers of Paleopanagia and the Turk-Albanians from Boliana in the mountains to direct water for irrigation purposes to the village:

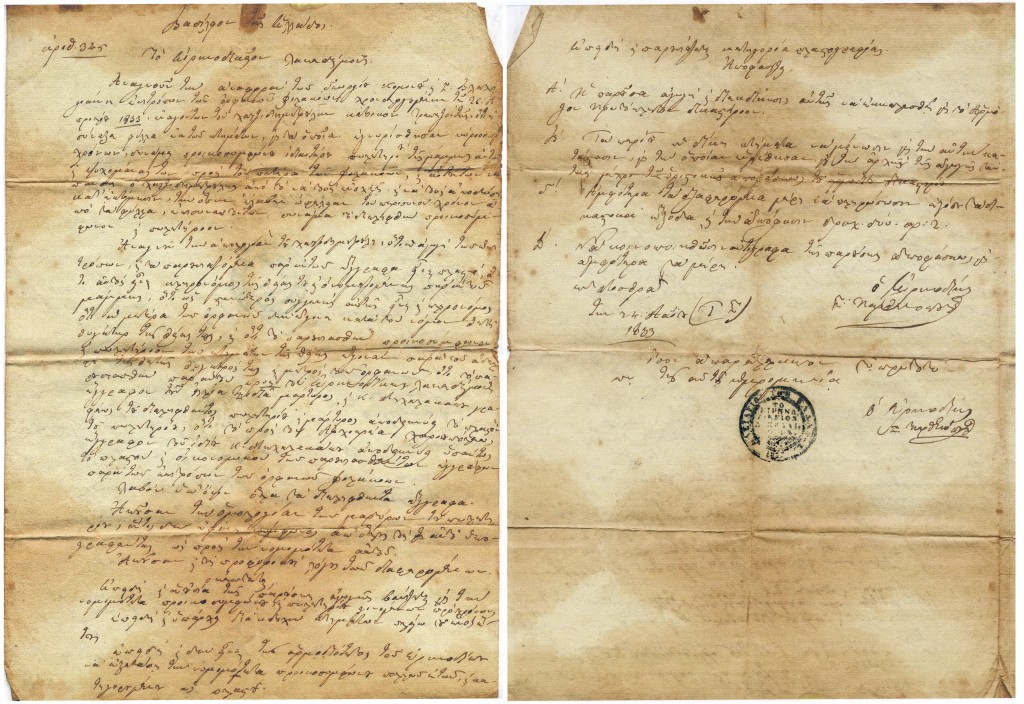

1833 – A decree asking citizens to register their lands and how they came to own them from the newly formed government after independence:

“When I found these documents, I took the stories from the relatives and put them in order. There was so much information. Much of the writing we could not translate because it was in the old Greek language not used today,” George said. I asked if the 1741 document gave the surname of the four brothers. He explained, “They had no last name, so they were known as Anagnostos which means uneducated. Turks did not allow Christian or family names. During those times, people took names from prophets of the Bible, kings and queens, or ancient Greek heroes. And children went to the churches to learn Greek secretly.”

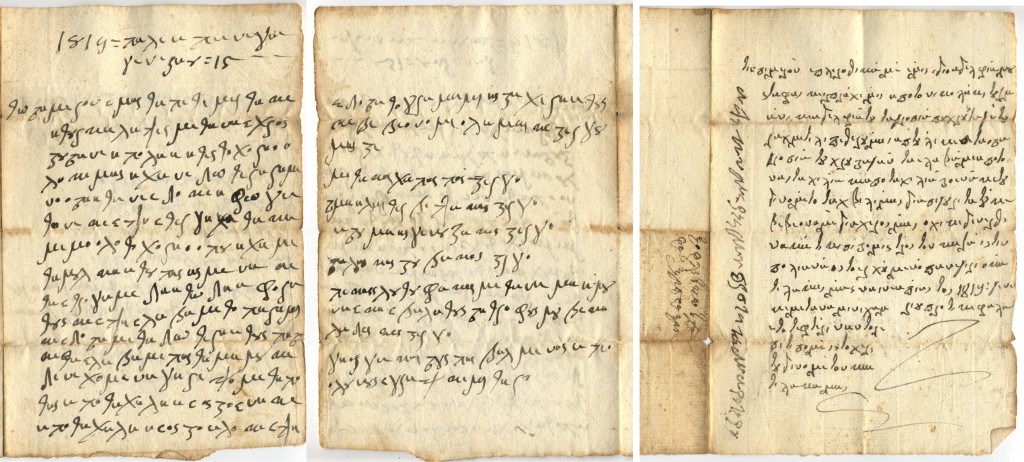

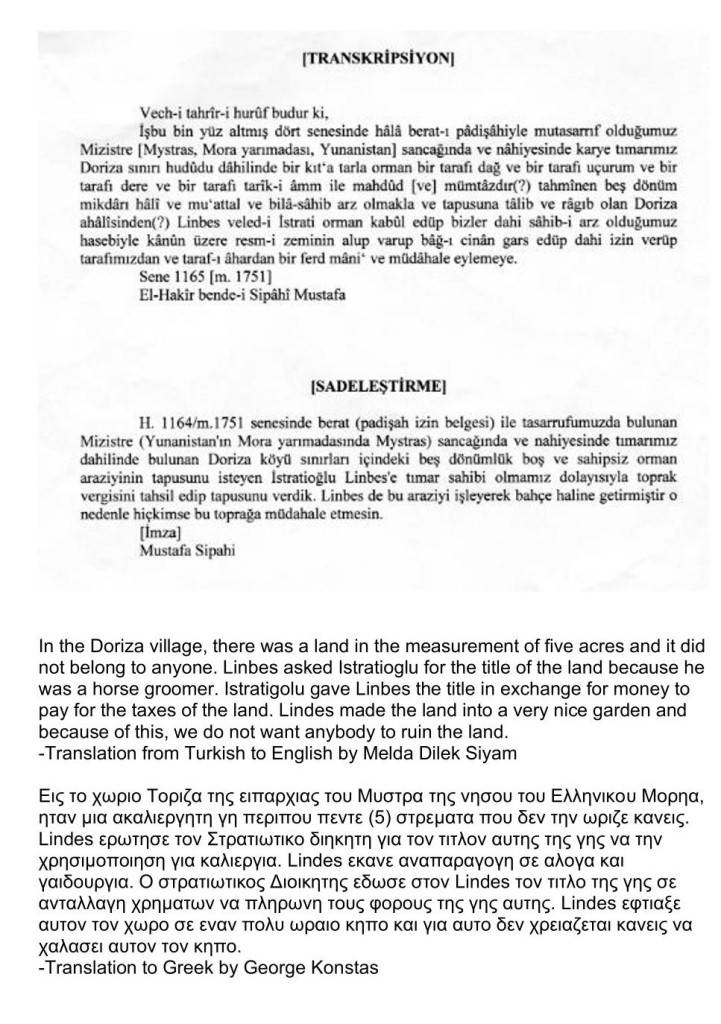

Also in the trunk was an amazing discovery—two documents, from 1751, written in Ottoman script!

First document and its translation:

Second document and its translation:

Translation of Ottoman script requires an expert. Although George had Turkish friends, they could not read the writing. In a unique coincidence, George knew of a man who worked as a translator for the Turkish government. George sent him the documents, and with great interest, the translator called George to ask how he had obtained them. After the documents were converted from Ottoman to modern Turkish, a teacher in Istanbul translated them from modern Turkish into English.

“Those documents and the true stories helped me to make the tree of my family,” George stated.

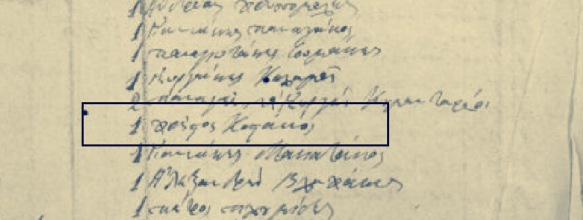

As he conducted further research in the areas of Paleopanagia and Xirokampi, George discovered the current day surnames of the four brothers:

- Theodoros’ descendants: Laspitis from Riviotissa, Sparta

- Stamatakis’ descendants: Nastakos from Paleopanagia

- Kyriakos’ descendants: Kyriakakos from Xirokampi

- Panagiotis’ descendants: Konstantarogiannis from Paleopanagia

George’s lifetime of work is now preserved in two books: The first is the history of the family from 1650-1821, and the second is from 1821 to present day. The books are written in his own handwriting, in Greek. With the help of his daughter, they will be translated into English. “I wrote these for my grandchildren, my daughters, and my family in the U.S. There are people we have not yet met, but they too will be able to learn the roots of the family,” George explained. Digital copies have already been sent to family members.

I had the privilege of meeting George on November 19 at St. Katherine’s Greek Orthodox Church in Falls Church, Virginia, where I was invited to give a presentation. He brought his books and we reviewed them, page by page. I was completely absorbed in learning of his stories and how he has preserved his family’s history. I remain both awed and thrilled with the meticulous and detailed work he has done. His work brings recognition and honor to his ancestors, especially to his parents, Pericles and Christophile, and his grandparents, Konstantinos and Amalia.

George understood the urgency in making sure the original documents were in a safe place where they would be accessible and preserved for future generations. I am so very pleased that he gave the originals and copies of his books to the Sparta office of the General State Archives of Greece. They are now safely stored and available for researchers to learn the origins of Konstantarogiannis and the other families descended from the four brothers, as well as to have access to rare documents from pre-independent Greece.

George’s passion is both infectious and inspiring. He helped me recognize that we have only a sliver of our ancestors’ stories, and that we must not give up the search. We never know what we will find, or where we will stumble upon new information that will help us understand those who came before us. Somewhere, there may be a trunk in your family.

I am deeply grateful to both George and his daughter, Christophile, for giving permission to publish this story. And especially, I give a huge thank you to George who drove two hours from his home to meet me that day at St. Katherine’s. Somehow, he just knew we needed to connect, and that his story needed to be shared!