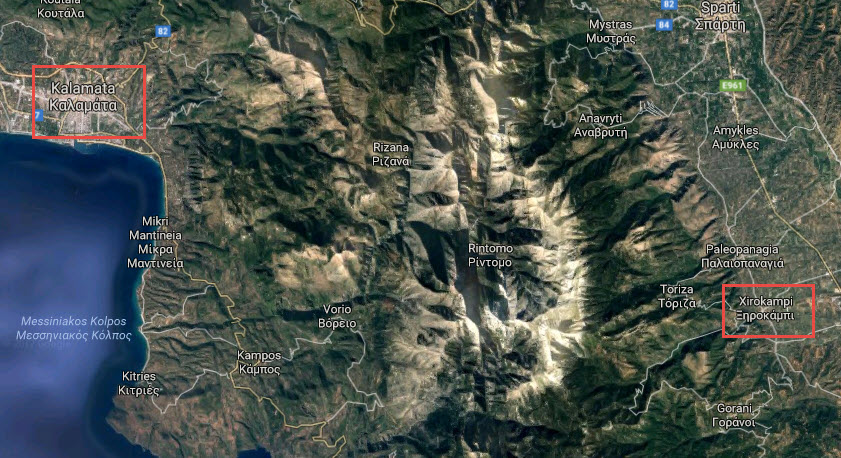

Going back in my family research always leads to the mountains. The Spartan villages of my four grandparents, Agios Ioannis and Mystras, were nestled in the valley beneath the Taygetos range. This was the agricultural center of the region—fertile plains filled with citrus and olive trees, fruit and vegetable gardens. As I wrote previously, villages in the valleys became repopulated after the Ottomans were expelled in 1830 and people descended from the mountain tops to start a new life. Among them were my grandparents’ ancestors.

Prior to the Revolution of 1821, Koumousta was the populated village; Xirokampi was a small settlement with just a few families. In the book, Koumousta of Lacedaimonos, Theodore Katsoulakos and Panagiotis X. Stoumbos meticulously describe life in Koumousta prior to the residents’ leaving. Among them was the Christakos family, ancestors of my paternal great-grandmother, Politimi Christakos, who married Andreas Kostakos. Her father, Nikolaos, and her grandfather, Dimitrios, are named in this book. Finding this information was an enormous and important breakthrough in my research.

The book describes the villagers: “Koumousta, from old times and until its desertion, was a very hospitable village. Everyone of Koumousta considered it an honor and pleasure to have someone under his roof. Work was stopped to settle the foreigners. Many people back then came to Koumousta from the plains and from surrounding villages. Relatives and friends were everywhere…Every Koumoustioti’s door was open to any foreigner that would knock on his door. The man who asked for hospitality was considered a “holy” [highly respected] person who should be treated with all arrangements of good relations. This treatment was highly characteristic and very good. Every good thing that there was in the house was offered with love and selflessness, and above all, food: cheese, bread, pork, eggs were the necessary and basic foods. Women put their hands deep into the barrels because there was where the best portions of pork meat lay after it was boiled. But it was not only the visitor that had to be treated well; even his mule had to be treated well. They took care to give the mule water and food, like their own animals.”1

This intrigued me. People would climb a steep mule trail to visit a village at the crest of a mountain? The villagers were known for their hospitality, despite living in an isolated area? I knew that Koumousta was situated on a high peak and that its access road was narrow and treacherous. But my ancestors were those described in the book, and I just had to go!

The journey seemed inoccuous at first. The road was paved, and a low stone wall provided a comforting border between the road and the ravine below. I felt reassured. But after a mile, the wall disappeared and the ravine’s treetops lined the side of the road. They were my guardrails throughout the four mile ascent.

The face of this mountain is particularly scary!

Partway up the mountain, I saw what appeared to be a lake on the right side of the road. But this is a man-made, rectangular basin. There are no structures adjacent to it, and I cannot imagine its purpose.

The road was extremely steep, and despite my growing fears, I had to keep my foot on the accelerator to keep the car moving upwards. Parts of the pavement were washed out, with evidence of small rockslides.

Seeing an isolated house, I wondered who would construct it mid-way up a mountain? It appeared to be abandoned, but at some point it was a home. How could one live so alone?

The phrase, “are we there yet?” kept running through my mind. I knew that the closer I got to the top, the worse the road conditions would become. I felt relief when I came across this sign.

Rounding a curve, my breath stopped when I saw the village: perched on the mountains were beautiful stone houses with red tile roofs. This appeared to be a viable village; I had expected crumbling vestiges of bygone years.

Driving onto the stone pavement of the plateia, I could not believe the scene before me. Koumousta was not a village in ruins. It was beautifully restored and utterly charming. I parked the car and in the town square; a black and white dog greeted and walked with me. The peace and beauty were almost magical.

One couple lives in Koumousta year-round; others come for holidays and vacations.

The inscription on the plaque mentions the restoration of the plateia in October 2000.

I can understand why my 3rd great-grandfather, Dimitrios, left and resettled in Xirokampi in the mid-1800s. I would bet, however, that if he were alive today, he would find a way to keep his mountain home. Although winter weather would make the road impassible and the cold intolerable (altitude of 2200 feet), this village remains a pristine oasis and a welcomed haven from contemporary life. Today, the village of Koumousta is also known as Pentavli.

1Koumousta of Lacedaimonos, page 213; translation by Giannis Michalakakos.