I love old photos–a moment frozen in time, an instant transport into the past. One collection that is especially endearing to me is the work of Swiss photographer, Fred Boissonnas, who traveled throughout Greece in the early 1900’s and photographed everyday life (see more photos here).

Seeing his photos of children and families fills me with curiosity about the early years of my grandparents, born in the late 1800’s. Last summer, I found School Records for their village of Agios Ioannis (St. Johns, Sparta) at the General Archives of Greece,

Sparta office.

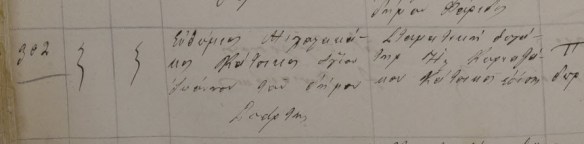

Mathitologion, Agios Ioannis, Volume E.K.P. 2.1.1

With gratitude to the kind and helpful staff who encouraged me to take digital images, I now have photos of some pages where members of my ancestral family are recorded. These documents are replete with insights into the families of the village in the early 1900’s.

Mathitologion, Agios Ioannis, School Year 1908-1909; page 11; Volume E.K.P. 21.1.

In this image, page 11 lists students for the school year 1908-1909. Because my great-grandmother, Afroditi Lerikos, was born in Agios Ioannis, I was looking for members of the Lerikos family. I found one on line 103: student: Lerikos, Anastasios, father: Dimitrios; age 7; born: Alaimbey; residence: Alaimbey; religion: Orthodox; father’s occupation: worker; student in class B. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Along with information about Anastasios such as his age and place of birth, this entry verifies that his father’s name was Dimitrios whose occupation was a “worker.” It also proves that the Lerikos family lived in Alaimbey which is a neighborhood or small hamlet of Agios Ioannis. This is an important fact when I am looking for records–I should be searching first and specifically for Alaimbey, and then for Agios Ioannis.

If a child attended school for more than one year, comparing his information in each successive school record helps me verify a specific birth year. In some books, the age of the child is given in years such as this example; in others, the birth year of the child is given. Either way, an exact birth year can be ascertained.

It’s All About Location!

Records in Greece are location-specific. My colleagues and I repeat, almost as a mantra, the following to new researchers: You have to know the original surname, and you have to know the village of origin.

In school records, I have found instances where children were born in one village, but resided and went to school in another. Knowing the exact birth location is critical. If I am looking for a baptismal record, I must look for a church in the village of birth. Looking for a church in the child’s village of residence will not yield the record. For records later in the child’s life, I would search his/her village of residence.

In the 1920’s, a new column with the heading “District Registered” was added. This signifies the district where boys only are registered in the Mitroon Arrenon (Male Register). This piece of data becomes critical in locating records, because I now know in which jurisdiction to look for information about the smaller villages. For example, Alaimbey is grouped with Agios Ioannis. However, records for the neighboring village, Sikaraki, are split: some are found in Sparta books and some in Agios Ioannis books. (Confusing, I know! But important.)

The following record for Ilias Nikolaos Panagakos shows that he was born in Parori, resided in Kalami in 1932, but is registered in Mystra. This leads me to search in three villages! (Click on image to enlarge.)

About the Parents…

School records record the name of the student’s father (mothers are not named) and gives his occupation. These two facts are essential in being able to differentiate between “men of the same name.” Naming traditions dictate that there can be several boys, about the same age, with the same name, in the same village.

It is both helpful and revealing to compare a father’s occupational information given in school records to that found in a Dimotologion (Town Register). Following a student through several years of school records, one can see if the occupation of the father changes. It is not uncommon to see that some men have two or even three different occupations. In the agrarian society of early 1900’s Sparta, most men were workers, farmers, landowners, or shepherds. But school records have revealed innkeepers, chauffeurs, wine producers, merchants, grocers, basket makers, masons and muleteers (I had to look that one up; it is a person who drives mules). Now that I know the names and occupations of the village families, I can visualize these people buying, selling, and bargaining with each other. This brings the village to life!

There are two occupations that especially caught my attention: “orphan” and “immigrant.”

When a father’s occupation was listed as orphan, it meant that the father of the student was deceased, but not necessarily the mother (remember, women are not named or categorized in these records; also, the column description specifically states “father’s occupation”). I have seen instances where, for example, in the school year 1908-1909 a child’s father’s occupation was landowner, but in the school year 1909-1910, the occupation was orphan. This gives me a year of death for the father, an important fact that can be difficult to find!

When a father’s occupation was listed as immigrant, this reveals that he is living overseas, most likely in the U.S. or Canada in the early 1900’s. The records indicate which school year the father was working in the village, and which year(s) he was listed as an immigrant. This gives me a specific timeframe to look for passenger ship records, which document where he was going and whom he was “going to” on the other side of the Atlantic. Knowing this migratory pattern is critical to understanding if, or when, the family eventually left Greece.

When my paternal grandfather, John Kostakos (Ιωάννης Κωστάκος) emigrated to Brooklyn, New York, he settled near his relatives and compatriots. I was excited to find their names in the village school records. These people grew up together, went to school together, and reestablished old ties in a new land. Very often, men arranged for their sisters to marry their schoolmates from the χωριό. Their relationships, forged as children, supported them throughout life.

About the Girls

Searching for female ancestors in Greece is extremely difficult as there are few civil records where they are named. However, girls who attended school are in the school registers, and their information is just as detailed as that of the boys. Distinguishing a girl’s name is easy because of the diminutive which is used both in given names and surnames. For example, Vasileios for a male; Vasiliki for a female; Lerikos for a male; Lerikou for a female.

Metsovo on Tap, 1913; photographer: Fred Boissonnas; http://www.lifo.gr/team/lola/34138

In the earlier school records, girls are listed together at the end of the roster so they are easy to find. As time went on their names were integrated within the roster, so looking at the diminutive is essential to correctly identify daughters and sons.

About the Family

Both boys and girls started school at age six or seven. It is interesting to see who attended for only one or two years; and who attended for several. How was it decided as to which child/children in a family went to school and which ones did not? Girls are students, so it was not a matter of sex or preconceived assumptions that girls stayed home to work while boys received an education. It is essential to examine records of every available school year so as not to miss a child who attended sporadically or limitedly.

Scrolling through the school registers of a specific village, the number of families living in that village quickly becomes evident. As I extracted family names, I could easily put together families by looking at father’s name, child’s birth year and village. Below is an example from my spreadsheet–these children share the same surname but it is omitted for privacy.

School Record Spreadsheet

Through my searches in Male Registers, Town Registers and Election Lists, I thought that I had a fairly complete picture of my early 1900 ancestors from Agios Ioannis. However, I came across four children of the same father who was not in my database. Through school registers, I was able to discover and piece together a family that somehow had been omitted in other records.

Despite occupations, wars and tumultuous periods, children continued to go to school. School records prove that some forms of everyday live prevailed, even under a cloud of fear or foreboding. Village histories, as well as civil records, document that education–even in remote areas–was available and important. The information in school records brings a new and exciting dimension to understanding the lives of my ancestors.