by George Theoph. Kalkanis

published in The Faris Newsletter, Issue 62, July 2015, pages 3-6

(Note: this post, “Water” is the second of three parts describing the earliest modern developments in Xirokampi. Part 1: Light, can be read here.)

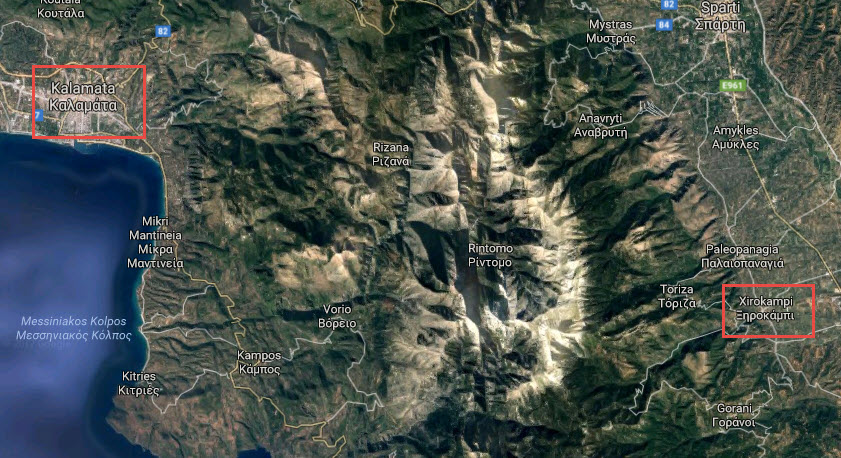

The construction of a complete network of drinking, running water with pipes in the village was attempted and completed in the 1960s or even the early years of the 1970s, during the presidency, initially of Georgios Koumoustiotis and then of Nikolaos Koumoustiotis. It was preceded by the construction of a small stone tank, under the presidency of Ioannis Karambelas and Efstratios Skouriotis, at the highest point of the village, at the exit of the Anakolo gorge. There, the water was collected with metal pipes from many small springs – such as Sotiritsa – that were expropriated by the state.

Initially – in 1953 or 1954 – “public” taps with brass spigots were installed in central points and in the large neighborhoods of the village. The network, made of metal pipes, did not supply these taps with water around the clock, due to its inadequacy. Thus, the sight of long lines of women with buckets, jugs or pitchers and wooden water barrels (. . . ) was a daily occurrence, from dawn. It was there that the women informed each other about the news of the village.

However, the public water fountains made the life of the villagers so much easier, that today’s children cannot imagine. Until then, the transport of drinking water was carried out by springs [“αμπουλάδες”] which gushed with a natural flow in the banks of the Rassina, from a small spring on the right bank of the Anakolo – at the height of the “Komnini” small lake; but also (after the middle of the 19th century) from wells dug in the village, at a depth of 4 or 5 meters, in various places: Iatrideika, Feggareika (of Kalamvokis or Magganiaris), Volteika, Poulakeika, Rassina (of Aivaliotis), Liakeika … All of the wells were communal. Of course, with the operation of the wells, the springs gradually dried up, since the underground water level went down due to constantly increased consumption, especially during the 1960s.

With the completion of the network and the replenishment of the reservoir, water reached every house in 1961 and 1962. But the process was long, arduous and costly. Trenches in the streets had to be opened with a pickax and a shovel. Pipes had to be bought, transported, placed and connected together. Then, the local handymen worked as plumbers in the public network and in the networks inside the houses: Giannis Chatzigeorgiou, Stavros Argyropoulos, Michalis Tsapogas and Elias Christopoulos. To deal with the large expenditure, the community rulers resorted to the then common measure of compulsory (co-)contribution from the inhabitants – alternatively or additionally – of money or oil, personal labor or the labor of their animals for the transport of the pipes and materials. Each family was estimated to bear the cost of 10 meters of the network.

The consequences of the construction of the water supply network were, of course, crucial for the quality of life of the inhabitants, but they also had secondary, controversial results. Horticultural production increased, but it was also necessary to transport water even from Taraila, bypassing the route of centuries and reducing the underground water. Undoubtedly, however, the project was large and innovative for its time, it improved the life of the inhabitants and attracted new residents from the surrounding villages, being one of the strongest incentives for them.

Part 3 of this series, The Telephone, will be published next.

I am honored to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the ninth article of the ongoing series. Previous articles can be viewed here.