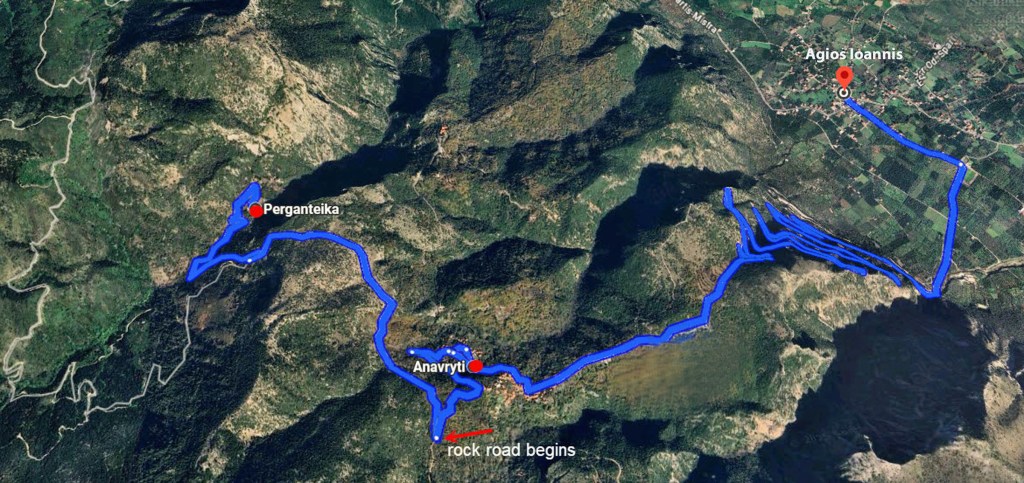

I can be a pretty determined person, especially when it comes to seeking out ancestral places. In 2019, I wrote a post about my futile attempt to drive to the deserted village of Perganteika: a settlement near the summit of the towering Taygetos mountains. At 5 km above the already-ridiculolusly-high village of Anavryti, Perganteika may have been a temporary residence of my great-grandfather, Andreas Kostakos. After 1840 when Greece was freed from Ottoman rule, it was common for families to leave their mountain homes, descend into the valley, and relocate in villages where the land was fertile and crops could be grown (see this post). Thus, it is highly likely that Andreas also moved from the high villages down to his permanent residence in Agios Ioannis.

The red arrow indicates the end of hardpack gravel and beginning of dirt and rock

Last month, I asked my cousin Panos if he would help me get to Perganteika. He was a bit incredulous. Why would I want to do that? It’s a terrible road, and no one lives there. Even when I explained that our Kostakos ancestor may have resided there, he was hesitant. He explained that although remote roads might be cleared after winter snows and spring rains, there is no way of knowing if that was done until one goes in person. It was only after Panos examined satellite maps that showed the road looked fairly clear did he agree to venture forth. Note: isolated mountain roads are not paved. At best, they are packed gravel, at second best they are packed dirt, and at worst they are neither — just a widened donkey path left to nature’s mercy.

Nevertheless, he said yes! On a Sunday evening, Panos and his sister and my daughter and I piled into his car for the great ascent.

The drive to Anavryti is always breathtaking. The panoramic views into the valley are humbling and always cause me to contemplate my miniscule place in this world.

As we enter Anavryti, the road guides us through the center of the village. There are no sidewalks, only narrow cobblestone streets. It is a charming place. In the early 1900s, numerous Anavrytians emigrated and settled in Brooklyn, New York, where they formed the Vyrseon Society to support each other in their new homeland. Many of their descendants return each summer to their ancestral village.

At the end of the village, the road turns left and we traverse the edge of the mountain. It’s not long before a sharp turn to the right takes us off the main road to hardpack gravel. Panos was right–the road had been cleared and it seemed quite navigable. I was excited to realize that we would really get to our destination!

The greenery on the left are not bushes, they are the tops of trees above the cliffs.

The remote landscape was green and brown; rugged terrain with a mixture of deciduous and pine trees, scruffy underbrush, and thorny weeds. There is absolute quiet and perfect peace. No people; no cars; no houses; no distractions. It felt almost sacrilegious to break the silence.

As we continued, Panos had to navigate steep terrain and rock-filled gullies. Downshifting and stomping on the gas coaxed the car up the inclines, but there were times it was frightening and dicey. Worried about car damage, I implored him to stop and turn around. But he knew the limits of his vehicle and they had not been breached. When the road eventually flattened and the curves ended, we entered into a clearing were stunned to see an edifice rise before us. It was the village church of Agia Triada. We had arrived!

Hearing its echo in the wilderness brought life to the abandoned settlement.

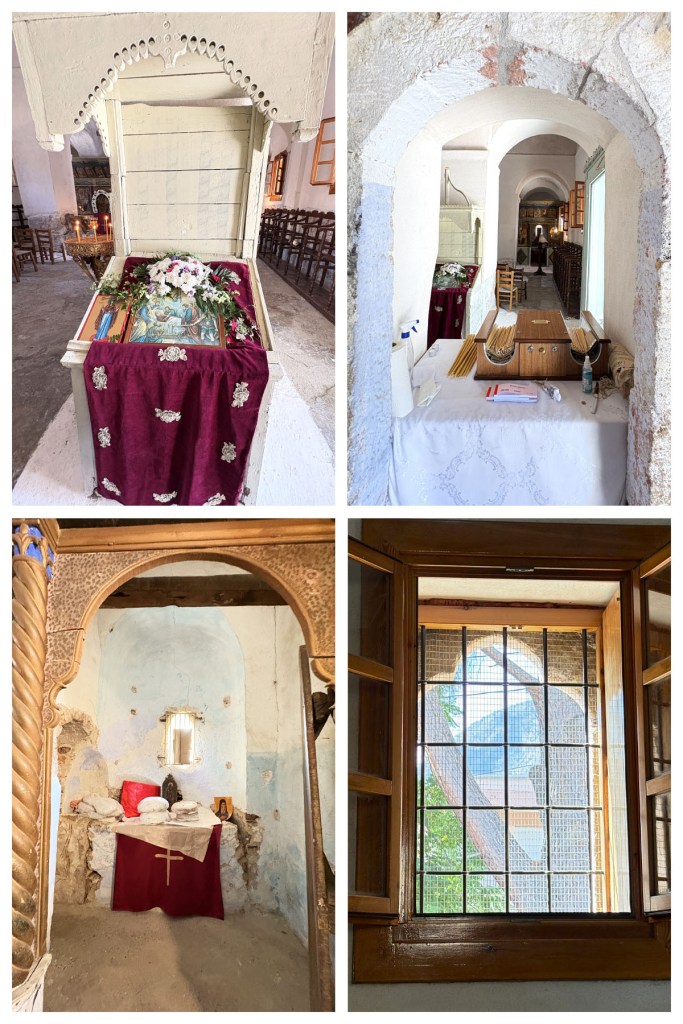

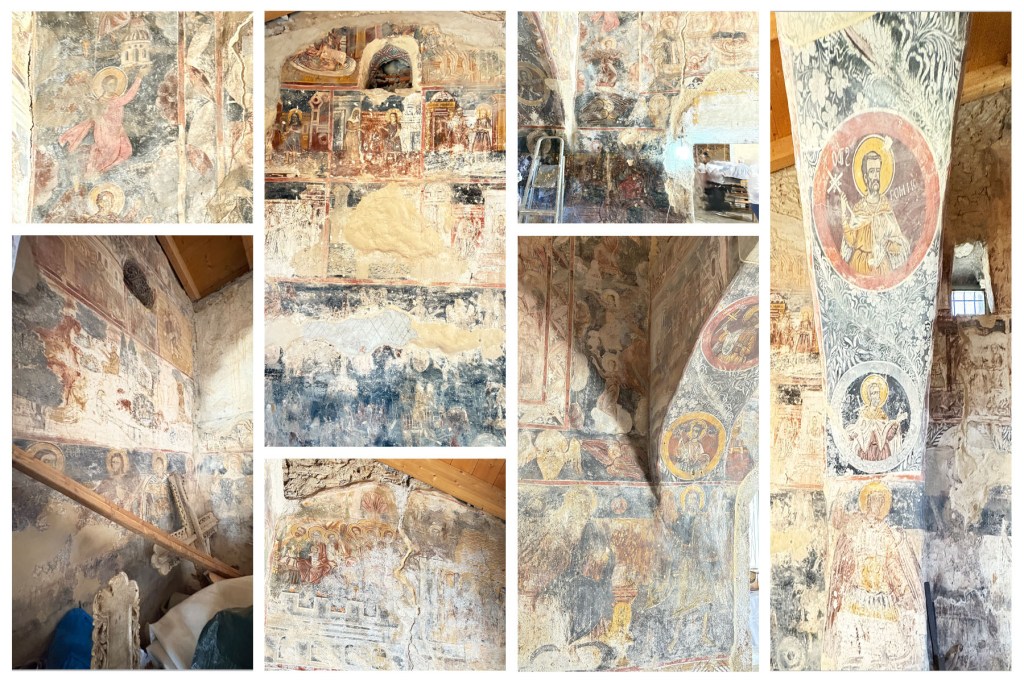

I became emotional as we entered this modest church. It was impeccable and beautiful inside. The altar and icons, the stone floor and wood ceiling, the proskynetarion1 and chandeliers–all were in perfect condition, ready for worshippers. There was even a page of hymns resting on the analogion2, waiting for the baritone voice of the psaltis (cantor) to resonate within the building.

As I absorbed the spirit of this holy place, this thought came to me: “in their poverty, they spared nothing to build this church.” No matter how miniscule or remote a Greek settlement, an Orthodox church will surely be built there.

The silk flowers, burned candles, and immaculate surroundings indicated that a service had been held recently. One of the priests from either Anavryti or Mystras would have chanted a liturgy to commemorate the church’s patron saint. Descendants of the founding families, among others, would have made the trek up the mountain for this yearly event. My cousin Joanne, who has been at the service, explains: “the service is conducted 50 days after Easter (Tou Agiou Pnevmatos ) and there is a big picnic afterwards at the platiea with boiled goats and whatever everyone brings. It is a fabulous tradition.”

We exited the church, carefully closing the iron gate at its entrance, and began walking the path down the hill. Our footsteps crunched on the gravel. The vegetation was wild and thick. We saw no wildlife, heard no birds. We spoke in low tones as if not to interrupt the silence. It felt as if time had stopped.

I didn’t know what we would find as we followed the path. Imagine our utter surprise when a stone tower jutted out from the treetops to our right! This was the type of tower that is found in Mani, the southern Peloponnese. Who built it here? Maniate settlers who had traveled north?

And houses! We saw two that were standing structures; one was outfitted with beds and sparse furniture. There were many that had crumbled into heaps of rocks, barely visible through the vegetation. The settlement had been populated by several resident families.

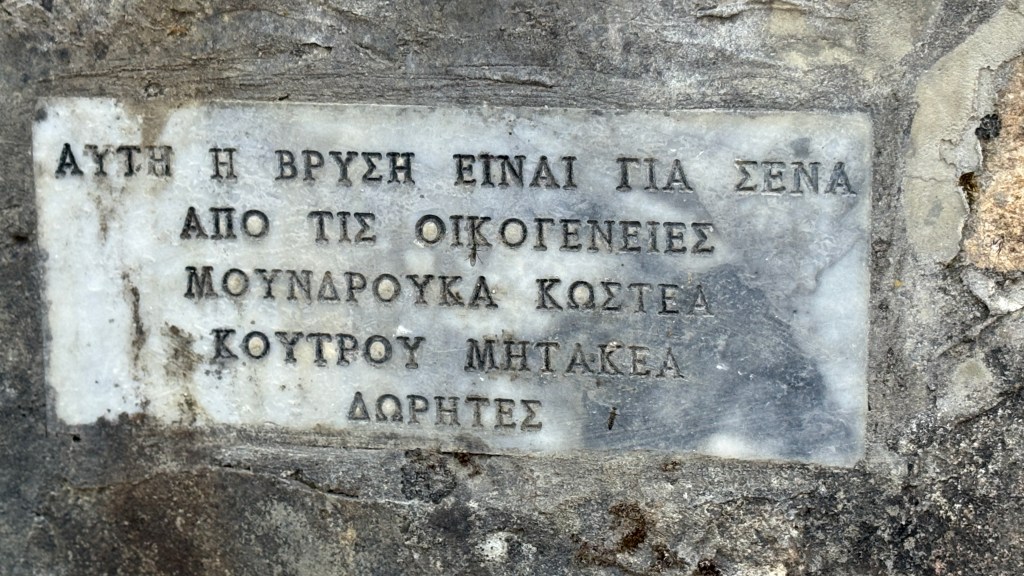

At the bottom of the path in a large clearing was the proof that Perganteika had been a viable community: a plateia with its plane tree in the center, and a fountain gushing frigid but pure mountain water. Large or small, every Greek village had these requisite, distinct features.

I read the transcription on the stone fountain: This water is for you from the families Moundrouka, Kostea, Koutrou, Mitakea, Dorites. From my genealogy research, I knew every one of these names. Some were in the scant records which exist for Perganteika and others were in the records of Anavryti. This, of course, made sense as official records in Lakonia began in 1840, at the end of the Greek Revolution and simultaneous with the period of downhill migration. I was thrilled to see these surnames–irrefutable proof that these families had lived here.

As we began our drive to the valley, the vista descending from Perganteika was even more spectacular than the one ascending. I cannot spot even a hint of Anavryti when I am in Agios Ioannis, looking up the mountain. Yet here we were, above the village looking down at its rooftops!

Thank you, Panos, for this marvelous experience! It is so very meaningful to me–if Andreas Kostakos did live here, even for a short while, I have walked in his footsteps. My curiosity is satisfied and my heart is happy.

1a wooden structure, holding a framed icon, where worshippers can approach, venerate, and light candles.

2a lecturn or stand specially designed to allow the psaltis to easily read the text.