by Carol Kostakos Petranek: Interview with Tom Frangoulis

How does a village history project evolve? In Egklouvi, Lefkada, it began with the name, “Polito.” When neither Tom Frangoulis nor his brothers could remember their grandmother’s given name, Tom embarked on a quest. He knew there had to be a record somewhere. “I was born in Egklouvi,” he explained, “and everyone in my father’s family was born, married and died there.”

Examining books at the archives and churches, Tom discovered that his grandmother’s given name was Polito. He also noticed that the Frangoulis name was written on page after page, year after year, going back in time. Way back– to 1760! “When I started building the family tree, all the branches were other families that also lived in Egklouvi,” Tom said. “The village didn’t have that many people, so everyone is related.” As Tom expanded his research into his mother’s family from another village, he concluded that “all of Lefkas is related to me!”

Tom’s passion for documenting his family’s history meant that his summertime visits to Egklouvi became research trips. “Starting in 2010, I would go to the archives for three to four hours a day, five days a week, for several weeks,” he stated. “I told the people there that I was interested only in my family research. I was not interested in making money or publishing a book – only my family history. After three years, they realized that I was not lying and they began to trust me.”

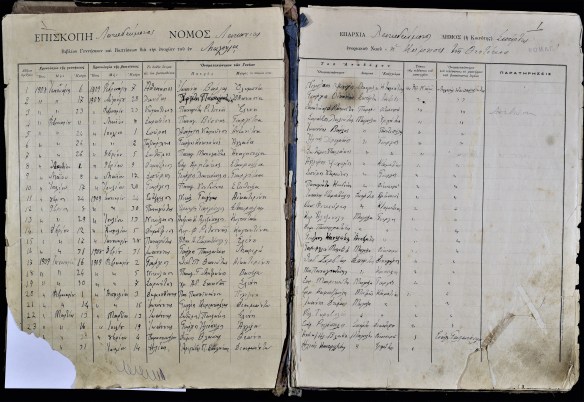

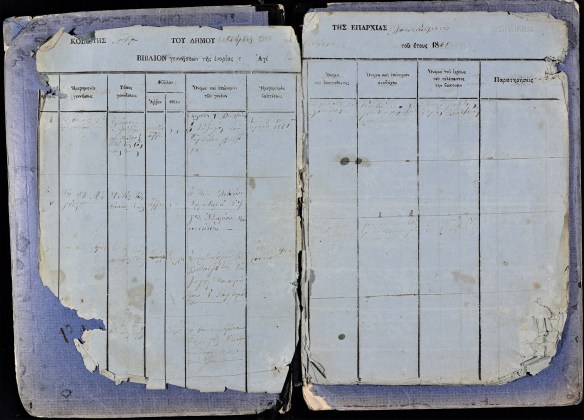

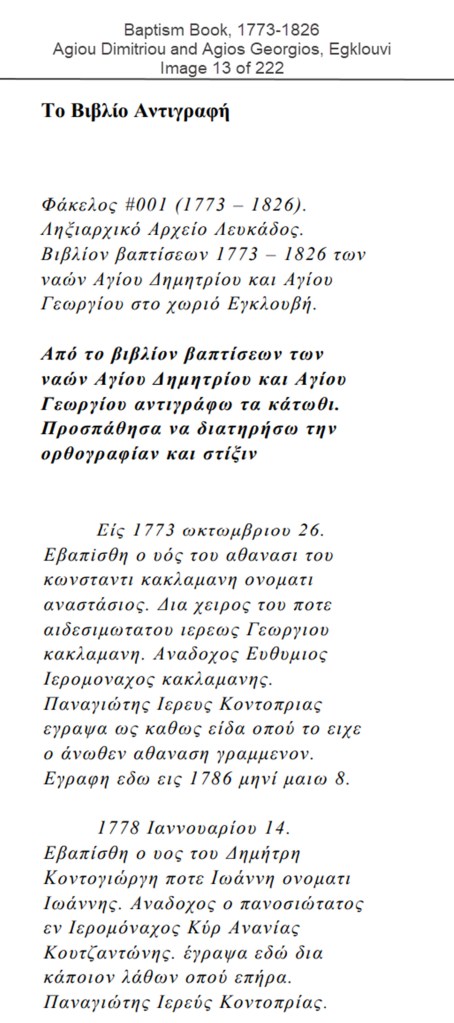

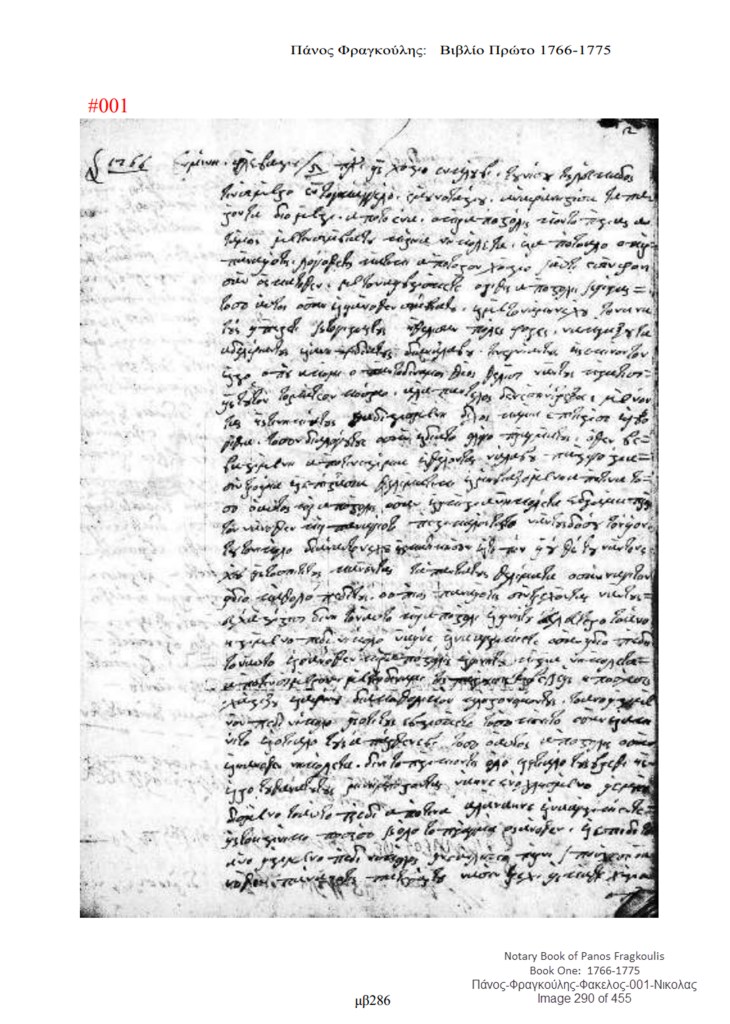

That trust, built carefully and honestly over the ensuing years, has enabled Tom to access records and documents not only at the archives, but also in municipal offices and city halls. Notary books on the island of Lefkada go back to 1760 and church records to 1770. At one point, the Greek government required priests to turn their church books over to the archive offices where they remain to this day. There are hundreds of books – civil and church – dating from 1750 to the early 1800s, and the late 1800s to early 1900s; however, there is little in between. “From 1840-1890, books are difficult to find or they don’t exist,” Tom observed. “The bridge for information in this timeframe is the Male Registers and Election Registers.”

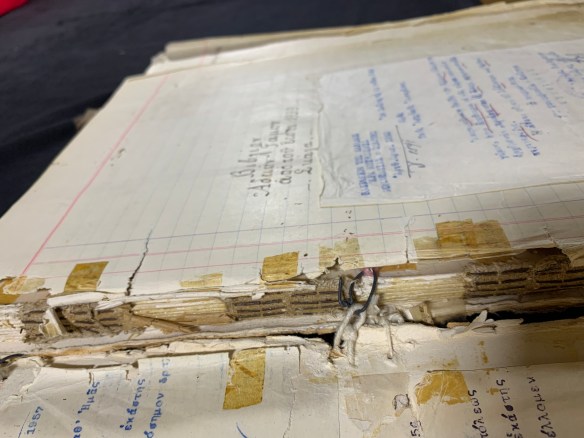

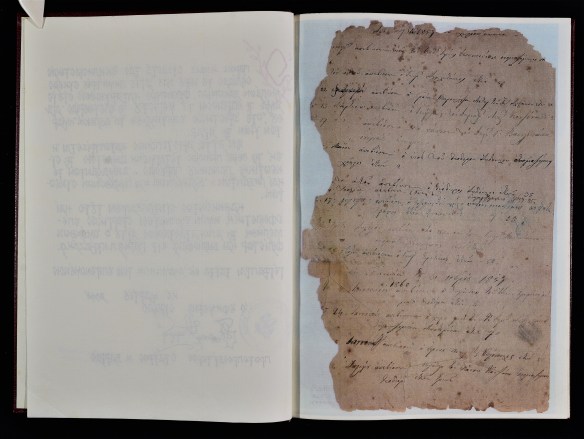

Another dilemma arose. “The books are fragile, and the ink has eaten the paper. I want the information, but I don’t want to destroy the books,” Tom remarked. He developed a two-part method to both preserve the records and extract the vital data.

First, he uses a camera to take digital copies of the original books. He then uses Photoshop to crop and straighten every photo, and to play with the brightness and contrast to ensure the image is the best quality possible.

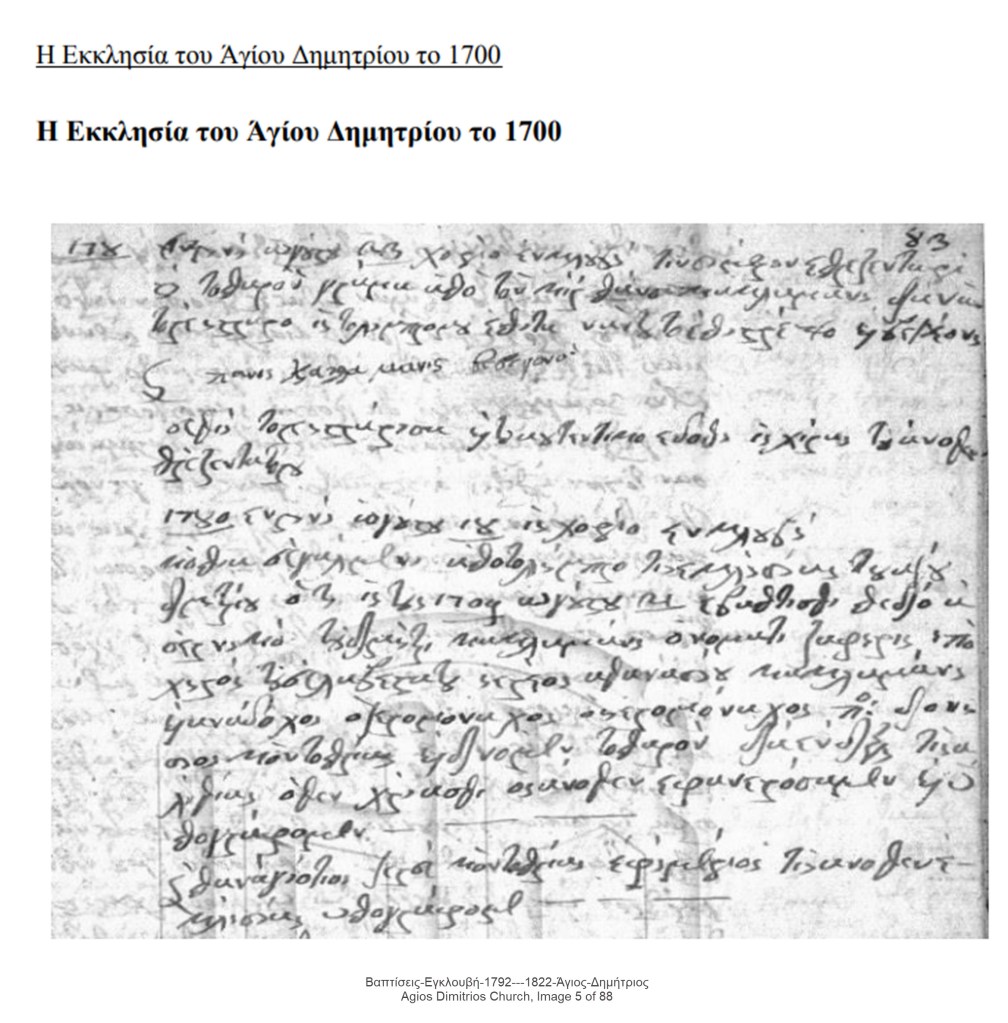

Second, he transcribes notary documents word for word. He reviews the pages and enters every name into an Excel spreadsheet. With church books that are names only, he types every name for every entry into a spreadsheet. He described his process: “I read the baptism book and create a line for the child — the date he was born and baptized; his name; the godparent; the father and the grandfather, and the mother (in later records). The forms are in alphabetical order. I analyze the records. Some books I analyze a little more to put together families.”

Tom transcribes the records into Greek, not English, because the villagers are then able to read his works, ask questions, and provide additional information. In turn, Tom helps them. “All I need is someone’s name, and I can take their family back to the 1700s,” he says with modest pride.

Reading the old, handwritten records—especially those from the 1700s—did not come easily. Tom explained, “In the 1700s there were very few people who could read and write, and that included the priests who were illiterate. When you read these books, you see that there were no rules in writing: one page is written as one long paragraph; there is no separation of words, no punctuation, no paragraphs, no periods, no capitalization. You must learn to decipher the handwriting of the person and then separate the words into sentences and paragraphs, so they make sense.”

Church records in the mid-1700s were written differently than today. In baptismal records, the name of the mother was generally omitted. Why? “Back then, people knew who the mother was because everyone knew all the families in the village,” Tom answered. “Sometimes not even a last name was written.” Also, priests recorded the names by which people were known. Since villagers used nicknames (paratsoukli) interchangeably with surnames, the priest could use either name in the record. Thus, correctly identifying families was a challenge. Tom learned that by comparing the given names of family members and parents, he could identify the family whether it used a nickname or a baptismal surname.

“After 1820, priests began writing both fathers’ and mothers’ names because there were several families with the exact surname in the village,” Tom commented. “Then, when there became too many with the name, paratsoukli were given as a way to differentiate the various families. My great-grandfather’s uncle got the paratsoukli, “PentEkotis (Πεντεκότης)” because he owned five chickens!”

Notary records—rich in facts about families and customs of the times—are an incredibly important resource for both historians and genealogists. Wills, dowries, real estate transactions, business agreements and sales of animals are written in exact detail, providing an intimate glimpse into the personal lives of villagers. “When you read them, you cannot separate yourself from the life that people lived. There were surprising things they did,” Tom said as he described a couple of examples:

1) “The general belief is that a dowry belongs to a man. Not correct. The dowry agreement is between the father and the mother of the bride and their son-in-law (the wife is not involved). There are three parts to a dowry agreement. First, the three parties go to the notary and the father and mother present a list of dowry items which could include trees, animals, land, household goods. All three agree on the list. Second, before the wedding, the son-in-law writes down everything he received so far – maybe three cows were promised but he only received two, and his father in law owes him one more. Third, the dowry belongs to the wife. If the husband mishandles one of the items from his wife’s dowry, he has to replace it.

2) “A husband and wife can write separate wills. A will written in 1550 in Kefalonia proves this point. Both the husband and wife were from Lefkada but ended up in Kefalonia. The husband wrote one will, and his wife wrote her own will, leaving her property in Lefkada to her children.” At the end of this post is an article that Tom wrote which proves this point, and verifies that the families Deftereos and Skliros lived in the village of Sibros in Lefkada in 1550!

3) “If I was selling a house and you wanted to buy it, how would we agree on a fair price? There were no appraisers back then and no one wanted to be cheated. The notary books explain how this is done. Both the buyer and the seller choose three people from the village whom they trust. One person from the buyer and one from the seller go to the house together, look at it, and decide on a price. Then, the next couple do the same thing, and then the third. When all three couples have decided on their prices (which could be very different), the sums are averaged and that becomes the sale price. Thus, there are no allegations of cheating after people from both sides agreed on a price.”

4) “You can feel the pain of the people in those records. In a will written in 1789, two brothers inherited their father’s property. The father had only one donkey and one cow. In the will, he leaves half of the cow and half of the donkey to each brother. The boys now have to decide how to split these assets. Both need the cow to plow, and both need the donkey for transportation. They find a way to share the animals equitably.

5) “These people were very religious. There is no will where they do not write where they want to be buried, and what they leave to the church. They would write that a specific property or item is to be sold “for the good of my soul” and the proceeds used to pay for the burial and as a donation to the church. In 1770 Egklouvi had seven churches and eleven priests. The churches were started by small groups of families, maybe three or four, with a congregation of 100-150 people. Then several families would start another church. If families could not maintain the church, they gave it to the metropolis.”

When Tom began researching his own family, he had no conception that it would eventually expand to a village (and possibly now, an island) history project. He started as each of us does—one person at a time. He emphasizes the importance of doing something, anything, no matter how seemingly small it may be: “Start with yourself. Get a folder and in it put your birth certificate, diploma, marriage certificate and important documents. It doesn’t take long to write a few lines; on one page, you can write the main events of your life. Then start a folder for your father with his documents, and one for your mother. When you get married start a folder for your spouse and children.

“People don’t realize how much information we have in our own hands. I used to talk to my mother all the time but I was not smart enough to write down at least the main stories she told. My parents were not educated and if someone doesn’t know how to write and read, they develop the skill of storytelling. My mother would present a story in a way that was better than any in a written document, but I didn’t write it down.”

Tom’s years of preserving, cataloging, and creating family histories are culminating into several written books. When the President of the village of Egklouvi learned of Tom’s work, he was very impressed and was instrumental in getting the books published on the official government website of Lefkada. Currently, four of Tom’s books are online and the government is waiting for additional volumes. Tom is now working on 30 additional books. “What is on the website is just a small portion of what I have,” Tom said. “If I can get a couple of people to help me, much more work can be done.”

Tom’s books can be found at https://lefkada.gov.gr/books/ebooks/. The books are in pdf format and free to download.

In summary, although Tom’s work is extensive, his philosophy is simple: “What is important is what you leave behind. We are living here for just a few years. Maybe our children are not interested in their past, but someday, someone will want to know ‘where did I come from? How did they live in the villages of my grandfather, my great-grandfather?’ You don’t have to go as far as me, but we all need to write something about our family.”

Below is the article about wills in the year 1550, referenced above: