We have pictures of the past, but not the full image. When I first heard Giannis Michalakakos make this comment, I accepted its veracity–but with reluctance. I want the full image of my ancestors’ lives! A Male Register, Town Register, or Election List may provide a birth year and an occupation. But a Contract reveals so much more. Who purchased land, and from whom and where? Who borrowed money, and from whom and why? Who was the bride, and whom did she marry? What did her family provide for her dowry?

On 11 July 1864, four men gathered at the office of Konstandinos Dimopoulos, notary of Sparta, to execute a dowry contract: Nikolaos Athanasios Kanakakos of Sikaraki (groom), Panagiotis Kavvouris of Agios Ioannis (father of Marigo, the bride), Georgios Stathopoulos of Magoula (witness) and Ilias Kalogerakos of Parori (witness). These men were engaging in an honored tradition that was instituted in ancient times and not officially rescinded in Greece until 1983.

A marriage dowry (prika) was a custom adapted from Eastern cultures. Created by economic need, it was prevalent an era when the roles of men and women were defined by a patriarchal society. Especially in mainland Greece, families generally were poor. Men were farmers, landowners, shepherds; or worked in handcrafts such making baskets, ropes, or leather items. Women were homemakers.

When a new union was formed, both were expected to contribute items needed to establish the home. The bride’s dowry provided household or clothing items, property or animals. The groom provided a house and income for the family. Thus, both bequeathed what they could to secure a foundation for their new marriage.

The Kavvouris-Kanakakos contract is translated below. It is a fascinating picture which helps us better understand the image of life in mid-1800’s Sparta. Commentary and historical information is added with footnotes or brackets, and photographs are representations of the types of items the dowry contains.

Page 1 of 4, Dowry Contract 463. Panagiotis Kavvouris and Nikolaos Athanasios Kanakakos, Sparta, Greece. July 11, 1864. Source: General Archives of Greece: http://arxeiomnimon.gak.gr/browse/resource.html?tab=tab02&id=197332

Contract 463, 11.7.1864, Dowry and Notary Deed

On this day, 11 July, Saturday, at 12:00 noon of year 1864, came before me, Konstandinos Dimopoulos, notary and citizen of Sparta, to my home and office, being east of the Church of Evangelismo of Theotokos,1 Panagiotis Kavvouris, estate owner and farmer of Agios Ioannis of Sparta on one hand, and on the other Nikolaos Athanasiou Kanakakos, farmer and citizen of the neighborhood, Sikaraki, of Agios Ioannis of the municipality of Sparta; both are familiar to me and of legal status. In my presence and the witnesses, they sign this dowry contract after my explanation of the laws.

Panagioti Kavvouris makes an agreement with Nikolaos Athanasios Kanakakos to give Nikolaos his daughter, Marigo, as his legal wife according to the holy rules of the Orthodox Church. The groom takes from the maternal and paternal legacy: 2

1. Two tall fezes (kind of traditional hat)

2. Gemenia – women’s head cover

3. Three basinas – a bowl for cooking

4. Three sets of kreponia – women’s clothing, dark in color

5. Twelve madilia – women’s head cover

6. One pair of vergetes– earrings, expensive

7. One silver cross

8. Three silver rings

9. One pair of crystal dessert plates

10. Six dessert spoons

11. One serving dish

12. Two men’s vests, decorated with fur

13. Ten women’s skirts

14. Two dresses

15. Twenty-five shirts

16. Twelve sets of underwear

17. Two men’s fustanella

18. Two disakia (small packages to hold items)

19. Two paploma, bed comforters

20. Ten soaps

21. Two makatia. decorative sofa covers

22. Eleven big pillows

23. Four small pillows

24. Two andromedes (unknown)

25. One peskidi (a nice throw cover for the sofa)

26. Two table scarfs/covers for the dining room table

27. Two nice scarfs/covers for chair backs and arm rests

28. Six fakiolia, small women’s head covers

29. Eight mpoiles, a kind of towel

30. Twelve spoons, knives and forks

31. Twelve plates

32. Seven mpouxades, wool cloth which hold liquids when making cheese

33. Eight vrakozones, traditional men’s clothing worn below the waist

34. Two casellas, similar to a hope chest which hold clothing and linens

35. Two kapaki, cooking pots with covers

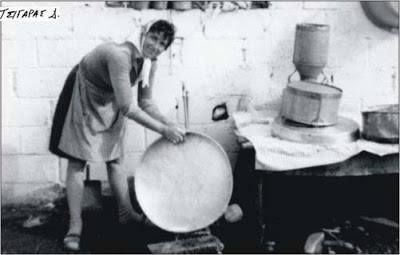

36. One tapsi, circular metal roasting pan used in ovens3

37. One harani – metal bucket that can hold one okres (a unit of measure)

38. Two siderostia – iron tripods to hang pots over an open fire

39. One pan

40. One stremma [unit of measure] with 14 olive trees located in the borders of Agios Ioannis, Sparta. The land is bordered: on the east with a national estate [land which belongs to the municipality], on the west with Panagioti Kamarados, on the north with Giannis Giannos, in the south with Georgios Bakopoulos.

41. One individual estate, a small field, two stremmata with all it contains [perhaps a small hut] and 7 small trees located in the location Sourakaki of Agios Ioannis, Sparta; it borders: on the east with a road, on the west with church fields, on the north with the national estate, and on the south with Pangiotis Pachigiannis.

42. Some trees that were planted in the national field in the location Kefalari of Agios Ioannis, Sparta; and borders on the east with Saltaferos [a family in Mystras], on the west with the road, on the north with Panagiotis Kavvouris and on the south with a road.8

43. Twenty barrels containing orange trees that the groom took a few days ago to replant them in his own land.

The total of the dowry and property (moved and unmoveable) is 1,463 drachmas.4

The groom, Nikolaos Athanasios Kanakakos,5 expresses that he accepts Marigo as his legal wife and the dowry given by her father. He understands exactly the dowry that was previously reported and offered to him by Marigo. He also offers Marigo 500 drachmas [bridewealth].6

The two sides additionally, with me the contract maker, evaluate the total value of all things as 1,963 drachmas plus the postcard [the notary’s fee].

To verify this contract and this dowry, the two sides listened to the dowry spoken aloud and clearly, and agreed to it.

Called as witnesses: Georgios Stathopoulos, estate owner and citizen of Magoula and Ilia Kalogerakos, farmer and citizen of Parori of the municipality of Sparta. They are familiar to me, they are Greek citizens without any legal exceptions, and they verify this contact because because neither of the two sides can sign their names.7

Maniate men in Sparta. Many people from the Mani region, like the Kanakakos family, moved north to Sparta after the Revolution.

I initially became acquainted–and fascinated–with contracts during my first trip to the Sparta Archives in 2014, when I went with Gregory Kontos. This 2015 post describes a contract, translated by Gregory, for the purchase of land by Panagiotis Iliopoulos of Machmoutbei. Each succeeding research trip has yielded new information, as documented recently in Research in the Archives of Sparta.

Contracts are challenging: not many are digitized or online, paper copies are difficult for Archivists to obtain, and the handwriting is akin to hieroglyphics. But with good luck and good friends, they can be accessed and interpreted, enlightening our understanding and giving us a fuller (albeit not full) picture of our ancestors’ lives.

Important note: This post would not have been possible without the assistance of Giannis Michalakakos, teacher, historian, and author of Maniatika blog. Giannis completed all translations, found the photos, and provided the historical content to explain the customs of this era. I am grateful for his friendship and expertise.

____________

1 This exact description of the location of the Dimopoulos home and office is given because Sparta in the mid-1800s had few roads and no street addresses.

2 Many of descriptive words come from the Ottoman period and are unrecognizable in today’s language; they may be a hybrid mix of Greek, Ottoman and Venetian vocabulary and are no longer in use.

3 When a meal is prepared using a tapsi, it is also served from it; the family would sit around and eat out of it together. A vethoura, the double pot on the right, is where sheeps’ milk is stored.

4 This is a sizeable dowry, indicating that the bride’s family had financial means.

5Kanakakos is a big family in Mani; members were officers in the Army and heroes in the Revolution of 1821.

6 As a bride brings a dowry, sometimes, a groom will offer a sum of money or property to the bride’s parents to help establish the new home.

7 Normally, there would be five signatures: the groom, the bride’s father, the two witnesses and the notary. In this contract, only the witnesses and notary signed as the groom and bride’s father were unable to write their names.

8 After marriage, land named in the dowry belongs to the bride’s husband. The property was given by her father to establish her new home. In 1800s Sparta, divorce was unheard of; and men were responsible for providing and maintaining financial security of the family.

I can see how this kind of history depth provides a more complete picture. I admire your, with Gianis Michalakakos, tremendous effort and research. It must be great for you to see a more detailed and in depth view of these lives. Thank you – Spyro