Those with ancestral ties to the modern municipality of Farida, Lakonia (villages include Xirokampi, Palaiopanagia, Anogia and several others) are immeasurably enriched by the writings of scholars from the area. The publication, The Faris, History, Folklore, Archaeology (‘Η Φαρις), has been produced semi-annually since 1966 and contains many hundreds of articles about the people, history, folklore, archaeology and culture of the region. An appendix in each issue includes notices of births and deaths of local residents. The publication was initially known as The Xirokampi and maintained that title from 1966 to 1977, when the name The Faris was adopted.

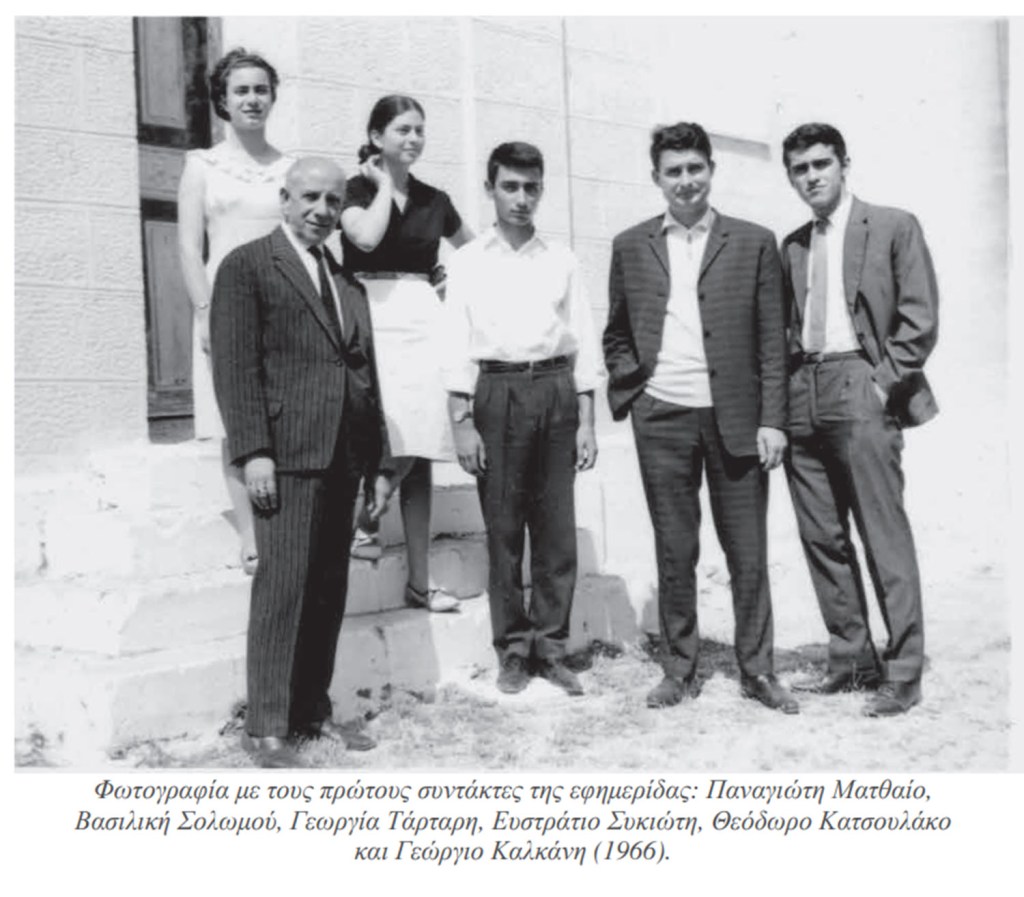

Those who write for The Faris descend from local ancestral families and know its past well. The founding editors, pictured below in 1966, were: Panagiotis Mathaio, Vasiliki Solomou, Georgia Tartari, Efstratios Sykiotis, Theodoros Katsoulakos, and Georgios Kalkanis. The current editorial committee is: Georgios Th. Kalkanis, Theodoros S. Katsoulakos, Panagiotis H. Komninos, and Ioannis Panagiotis Konidis. These, and dozens of other authors, have made Τhe Faris periodical a vital and unique resource to study the people and times of rural Lakonia.

The founding editors, from the 50th anniversary issue of The Faris, April 1996: left-right: Panagiotis Mathaio, Vasiliki Solomou, Georgia Tartari, Efstratios Sykiotis, Theodoros Katsoulakos, and Georgios Kalkanis

All issues of The Faris can be accessed here. This link is to an index of articles from 1966-2001. This link is to the e.faris website.

I am honored and humbled to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the first article of the ongoing series.

The Endings in -akis and -akos of the Surnames of our Region

author: Theodoros S. Katsoulakos

published in The Faris, History Folklore Archaeology, March 2007, Issue 42, pages 3-6

URL: http://micro-kosmos.uoa.gr/faris/pdf/faris_42_mar_2007.pdf. Note: Footnotes in the original publication have not been translated.

The writing of a historical study presupposes the existence and substantial utilization of evidence and historical sources. However helpful the assumptions may be, if they are not supported and confirmed by direct or indirect evidence, no opinion can be substantiated or founded.

In our area, the wider region of the municipality of Farida, if one excludes a few monuments, remnants of the distant past, few writings have remained from the years of the four centuries of Turkish rule. The latter is explained if we take into account the low (intellectual) level of the Greeks of the time and the bloody struggle for the liberation of the country, during which everything that was left was destroyed.

Fortunately, the monasteries saved some written sources of the Turkish Occupation: their contribution in this field as well was undeniable. In particular, a number of documents from this era are preserved in the monastery of Zerbitsa. Some of them are from the 17th century and more from the 18th century. These are notarized sales, exchanges, wills of monks of Zerbitsa and Gola. The monastic zeal protected the assets from various schemes in moments especially of anarchy and fear. It is surprising and impressive, of course, how these historical documents reached us, while it is known that the monasteries of Zerbitsa and Gola were attacked, suffered disasters, and their administrative status changed.

The language in which these witnessed agreements are written is Greek, with a standard that is an amalgam of colloquial language and elements from the legal and religious tradition. This means that this bipartite contract concerned the Greeks and was of value only to them. From the study of many jurisprudential documents of the monasteries in the region, it emerges that there are very few Turkish words that had infiltrated and these concern terminology closely related to the financial interests of the conqueror, such as mulkia, from the Turkish mülk, meaning private property, lakas, possibly a Persian word (alaka), meaning share, and amanati (bequest), which survives to this day.

The documents and various records are reliable witnesses of the presence of the families in our place, such as: Komnenos (1465, 1762 onwards), Goranitis (1634), Laskari (1634, 1751 onwards), Aliferis (1698), Menouti and Sahla (1751), Meropoulis (1753), Karadontis (1754), Konidis (1754), Stoubou (1754), Koutsika (1757), Theofilakou (1757 and 1776), Tsaggari (1757), Niarchou (1759), Moutoula (1760), Rizou (1761), Papastrati (1764) Fragki (1764) Mathaiou (1769) Kalkani (1789) Vourazeli (1795), Psyllou (1796), etc.

Of great interest is the information provided by the documents regarding the diminutive endings in -akis, which are proportionally more than the corresponding endings in -akos.

- –akis: Angelakis (1826?), Athinakis (1757), Aleiferakis (1752) and Aleiferis (1698), Anagnostakis (1829), Anastakis (1757), Antritzakis (1680), Venetzianakis (1769), Giannakis (1755), Grammatikakis (1769), Dimitrakakis (1788), Zoulakis (1751), Konakis (1818), Kanellakis (1757), Kapetanakis (1763) and Kapetanakis-Venetsanakis (1830), Karkampasakis (1766?), and Karkampasis (1815), Kom(n)inakis (1755) and Kom(n)ynos (1763), Konomakis (1752), Krotakis (1784), Lamprinakis (1764), Lygorakis (Grigorakis) 1793, Liampakis (1813), Mathaiakis (1769), Markakis (1780), Markoulakis (1680), Meropoulakis and Meropoulis (1744?), Nikolakakis (1824), Xanthakakis (1826?); Panagakis (1744?); Papadakis (1698), Patrikakis (1752), Petrakakis (1779?), Posinakis (1680), Rigakis (1832), Rizakis (1749?), Rozakakis (1762?), Stathakis (in an undated document), Stamatakis (1751), Stamatelakis (1698), Stampolakis (1759), Stratigakis (1751), Tarsinakis (1755), Tzakonakis (1830), Feggarakis (1755), Fragkakis (1812) and Fragkis (1764), Chaidemenakis (1805), Chelakis (1793), Christakis (1773).

- -akos: Anagnostakos (1800), Anastasakos (1830), Andreakos (1766), Antreakos (1766?), Apostolakos (1816), Armpouzakos (1819), Vatikiotakos and Vatikiotis (1798), Giannitzarakos (1832), Grigorakos (1784), Thanasakos (1763), Kavourothodorakos (1815), Karadontakos and Karadontis (1754), Katsoulakos (1825), Kostakos (1830), Lamprinakos (1764), Liakakos (1789), Maniatakos (1789), Marinakos (1823), Menoutakos (1751), Xepapadakos (1788), Panagakos (1830), Papastratakos (1826), Solomakos (1788), Stathakos (1824), Stratakos (1826), Tzolakos (1786), Christakos (1789).

After 1830, the ending of -akos began to prevail in the region. Useful conclusions are drawn from the study of the report of the local notables of the region to the Holy Synod (1835). It is noteworthy that only one surname was found ending in – æas (Niareas 1826).