One act of kindness can expand into ripples of eternal importance. Our family is—and will forever be–indebted to the Saltaferos household for the kindness and assistance extended to my paternal grandfather, John Andrew Kostakos (Ιωάννης Ανδρέας Κωστάκος).

John Andrew Kostakos

This is the story that has been related for years by several Kostakos elders.

In 1879 in the verdant farming village of Agios Ioannis, Sparta, John was born to Politimi Christakos Kostakos and her husband, Andreas. She died shortly after his birth, and by age eight John was orphaned. He and his siblings lived with various relatives until they were taken in by their half-brother, Gregory, and his wife, Maria Theodoropoulos, who had eight children of their own.

Life was difficult for John and he did not have the opportunity to receive a formal education. When he was about fourteen, he left Gregory’s home to work for Saltaferos, a wealthy man of Mystras. John was employed as the family chauffeur, and his responsibilities were to drive beautiful horse-drawn carriages and to take care of the horses and stables.

Family lore is that Saltaferos was considered ruthless and even heartless in his business dealings, cheating farmers by tipping the scale when their goods were weighed and “stealing them blind.” One graphic story recounts that upon his death, his most bitter enemies dug up his grave, removed his clothes, and returned his naked body to the casket.

However, to his employees, Saltaferos was known for being caring and generous. He and his wife were childless, and he took great interest in the well being of the young people who worked for him. He considered his female employees as goddaughters, marrying them off when they became of age and providing their dowries. He liked my grandfather, John, and made him the manager over the other boys who worked for him. John earned this respect when he proved his honesty.

One day, unbeknownst to John, Saltaferos spread some silver money under the hay in the stables. The next morning, John told the other boys to start cleaning the stable. As he worked with them, John found all the coins, about six or seven drachmas. He went to Saltaferos and said, “’I found some money in the stables, and it’s not mine. Do you know who lost it?” Saltaferos replied, “Well, give it to me, John, and I’ll find out.” John never knew that the money had been planted to test him. A couple of years later when John was corresponding with his brother, Bill, who had emigrated to America, he realized that he would have better opportunitities there. He told Saltaferos he wanted to leave and that his brother would send him the fare. Saltaferos replied that he would hate to see him go, that he would miss him, and that he would give John the money to travel to America. As my relatives proudly said, “He liked John so much that he gave him the money — that’s what honesty will do.”

I love this story. It reveals my grandfather’s character and soul, sets a standard of integrity for our family, and fills me with gratitude that I am his descendant. Although I do not know which Saltaferos man provided him the work which lifted him from poverty to independence, I hope the family will know that they are recognized and remembered with my deepest gratitude.

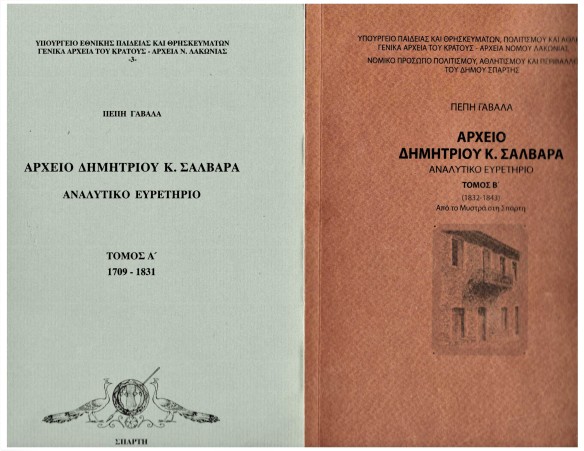

This story drove my curiosity about the Saltaferos family—their wealth, business dealings and standing in the community. During one of my “research summers” in Sparta, Pepi Gavala, Archivist of the Sparta Office of the General State Archives (GAK), gave me two books she published with abstracts she made of the files of Dimitrios K. Salvara[1], a notary in Mystras in the 1800s.[2] It was here that I found dozens of references to the Saltaferos family, their business ledgers, letters and transactions.

Gavala, Pepi; Archives of Dimitrios K. Salvara, Notary, Detailed Index Volumes A & B; Sparta, 2001, Ministry of National Education and Religions, General State Archives of Greece – Archives of Lakonia

I have translated every entry mentioning the Saltaferos name into a document that can be accessed here. My translations are amateur and imperfect; some of the words are of Ottoman origin and cannot be properly translated into either Greek or English.

These abstracts are incredibly fascinating to read. They are a window into the lives of people of Mystras during the historic period of the pre-Revolution through the birth of the new Greek state. This post is sorted into categories; the abstracts tell the stories.

Mystras, 1890. Library of Congress

The household of “Chatzi”[3] Saltaferos was among the affluent and notable families of Mystras. His sons, named in the Salvara books, were: Giakoumis/Diakoumis, Dimitris/Mitros, Nikolaos, and Ioannis/Giannos. They were businessmen with operations in Mystras, Nauplion (then the seat of government), Constantinople and numerous villages in Lakonia.

The brothers engaged in the purchase and sale of commodities and in shipping and trading. Ledger entries reveal transactions dealing with: olive oil, rope, caviar, bottles, raki, wine, beer, pipes, silk, pistols and rmaments, gold, corn, sheep, goats, salt, fish, straw, grains (wheat, semolina, barley). The family was engaged in auctions of homes and properties, and was active in the purchase and rentals of trees in “national olive tree groves.” Today, the Saltaferos operation would be considered a conglomerate.

These abstracts reveal the varieties and complexities of business transactions:

- #1036. 9,04 – Sparta, 25-01-1835. Payment receipt. Accepted for the amount of 200 drachmas kept by N. Saltaferos on behalf of his brother D. Saltafero and D. Maltziniotis from Em. X. Tsouchlo, for the rentals of the national olive groves of Parori and Agios Ioannis.

- #106. 2,52 – Constantinople, 22-11-1820; Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Constantinople) to Konstantine Salvaras (Mystras) reporting on shipping and trade.

- #135. 2,81 – Anapli [Nauplio], 14-03-1823: Letter from Dimitri to Konstantine Salvaras reporting on financial, commerical and economic transactions.

- #131. 2,77 – Trinisa, 13-11-1822; Letter from Giakoumi C. Saltaferos (Trinisa) to Konstantine Salvaropoulo mentions the delivery of fish and care for straw and barley.

- #554. 5,48 – Mystras, 28-05-1831. Letter from N. Saltaferos to Konstantinos Salvaras. It refers to the storage of two shipments of semolina in the store, however, the one from Chrysafa cannot be entered separately. That is why he suggests that they send it to him separately from each threshing floor and thus store it, so that they do not get confused.

- #148. 2,94 – Anapli [Nauplio], 16-11-1823 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Anapli) το Anagnostaina Salvara (Mystras). His request is stated for the care of the olives by the family and not by foreigners.

- #172. 2,118 – [no location] – 02-09-1824 – Ledger. Transaction accounts of Dimitri Saltafero (oil, rope, caviar, bottles, raki, pipes).

- #821. 7,35 – Mystras, 01-05-1833. Account. Account for the shop between Ilias Karteroulis and Konstantinos Salvara (to give to Ioannis Efstathiou, Nikoli Alexaki, Mitro Saltafero, etc. and to take from wine, beer, cash, income, oil, corn, etc.) In total, Ilias Karteroulis will give 17.911,27 grosia and will take 4.341,13 grosia.

- #187. 2,133 – Anapli [Nauplio], 10-03-1825, Letter from Dimitri Saltaferou (Anapli) to Antoni Salvara. Mentioned are family (Konstantine’s stay in Nauplio) and financial (gold purchases which have not yet been sent), their cases.

- #880. 7,94 – Nauplion, 23-10-1893. Letter from Anagnostis Tzortzaki (Nauplio) to Nikolaos Saltafero, Mitro Saltafero and Antonis Salvara (Mystras) in which he informs them that today the auction of the olive grove in the name of Ilias Karteroulis ended, that is, for them, 23,550 drachmas, which was raised because the gentlemen did not agree, but Karteroulis agreed and gave I. Efstathiou and Sarantari half, which he finds better. He asks them for their opinion.

- #1284. 11,48 – Mystras, 01-09-1837. Proof of Rent. Antonis Slavaras will rent his shop in Aletropazaro, opposite N. Saltaferos, to G. Giorgiklakis for 140 drachmas, which he will pay every four months. Saltaferos also gives him four cypress barrels of wine and three jars of oil which he found inside.

- #1311. 11,75 – Mystras. 25-11-1837. Ledger. Store of the tenants of Tripi, Mr. Mitros Saltaferou and Captain Antonis Salivaras and Emmanouil Economopoulou. I note all the olive presses of the caretakers and the meterikia [a unit of measurement of cereals], and I set up the ‘botzes’ [wood or clay vessels to measure, store and transport liquids such as wine.] The recording is made by olive press – ecclesiastical, Logastra, Katochoritkio, Politi.

- #121. 2,67 – Mystras; date: 02-11-1821: Work Contract . Mitros Panagakos declares that he will deliver 60 bottles of oil to Nikolakis Krevvata, “for cutting the olives where I touched” in Parori. Witnesses: Dimitri Nikolakos, Dimitri C. Saltaferos.

When problems arose, lawsuits and complaints to police and civil authorities were filed.

- Forgery, counterfeiting: #1049. 9,17 – Sparta, 3-05-1835. Report. The citizens of Sparta, S. Giannakopoulos, Giannakos Tzannetakis and F. Karamalis are complaining to the Municipal Committee for the election of the Mayor of Sparta against those who cannot lawfully vote – Ioannis and Nikolaou Korfiotaki, Dimitriou Saltaferou, Dimitriou Manousaki, A. Kokkoni and A. Salvara after D. Manousaki, because they have been accused of forgery and have not yet been acquitted, and of Ioannis Korfiotaki as illegitimate under surveillance for the crime of counterfeiting in the year 1830. Exact Copy 26.05.1835. Signed: Magistrate A. Tzortzakis

- #1474. 13,65 – Sparta. 17-10-1839. Lawsuit. Lawsuit of N. D. Petropoulou against Antonios Salvara and announcement of a lawsuit against N. Saltafero, regarding the price of oil.

- #1025. 8,120 – Sparta. 02-12-1834. Petitions-Protests. Report-protest of A. Kokkonis, according to the Justice of the Peace Spartis, to which he is protesting against N. Saltaferos, D. Manousakis and A. Salvaras, with whom he rented [homes] the first two were Koutzava and Koutzava Karveli and the third was Sitzova. For the payment of the third installment, however, the citizens did not pay and Kokkonis pays them and protests against them for all the damages and expenses he suffers.

- #1560. 15,23 – Sparta. 08-09-1841. Court Document – Complaint. Counterclaim/response of Dimitrios Saltaferos, reident of Mystras, against Anagnostos Tzortzakis, resident of Kastorio, on accountability for rent and late payment of the share of Parori rights. Was served 10-09-1841.

- #397. 4,24 – Nauplio, 07-06-1829. Report of Konstantinos Salvara (Nauplio) to the Justice of the Peace of Nauplio, in which he accuses that General Floros Grivas forcibly kept from him 460 grosia of the 1,160 grosis owed to him by the Dimitris Saltaferos. Now, “where justice shines” seeks compensation.

The Saltaferos brothers loaned money to their contemporaries and kept careful track of invoices to be received, accounts to be paid, debts owed to them, and problems encountered. Businessmen had open accounts where items were purchased “on credit,” and debts were paid after a harvest or a transaction.

- #1540. 15,02 – Sparta. 11-01-1841. Oral Complaint prepared at the Police Office by Antonis Salvara and Anagnostis Kokkonis against the shepherds and masters of flocks regarding damage to the olive fruit due to their sheep. The shepherds named in the complaint were: Dimitrios, Georgios, Vasileios and Spyros Alexandropoulos, Stavros Nikolakakos, Ioannis Vlachos, Dimitrios Saltaferos, Panagiotis Vlachakos, Dimitrios Darmo and Panagiotis Mourgokefalo, Georgios and Petros Adamakaios and Diamanti Chachalako.

- #141. 2,87 – Anapli [Nauplio], 13-08-1823 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Anapli) το Konstantine Salvara (Mystras). Τheir economic and commercial affairs are reported. He is particularly concerned with unsold goods.

- #153. 2,99 – Anapli [Nauplio], 06-02-1824 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Anapli) το Antoni Salvara (Mystras) in which he urges him to sell the goods and send the money to be debited.

- #157. 2,103 – [no location] 01-03-1824 to 12-08-1824, Ledger. Detailed account of goods and debtors; what Antonis owed to Mr. Georgakis Pygeraki; what goods were sold to Mitros Saltaferos of Mystras.

- #161. 2,107 – Agiantika, 09-04-1824 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou to Konstantine Salvara (Mystras). Mentions shipment and invoice, and his desire to sell the goods even at cost to get his grosia [money].

- #1401. 12,80 – Sparta. 15-12-1838. Note. Note of G. K. Feggara (Sparta) to his “friend and brother” Antoni Salvara, in which he is worried about the 500 drachmas which should have been in corn to Mr. Mitros, who complains it was not given to him. Please give it to him as they have agreed.

- #1560. 15,23 – Sparta. 08-09-1841. Court Document – Complaint. Counterclaim/response of Dimitrios Saltaferos, reident of Mystras, against Anagnostos Tzortzakis, resident of Kastorio, on accountability for rent and late payment of the share of Parori rights. Was served 10-09-1841.

Under Ottoman rule, numerous taxes (Ottoman tax) were levied. Payment of the “tenth” or tithe which went to Ottoman authorities was mentioned several times.

- #783. 6,147 – 1832. Ledger. Name register of Agios Ioannis. “where we have the revenue of Parori, a tenth is owed by everyone.¨ Specifically, it is recorded that “every tenth Paroritiki goes to the olive press of Agios Ioannis of D. Saltaferos.” [Note: 1/10 tax was levied on everyone by the Ottomans. Here, the tenth owed in taxes is paid in oil; the people of Parori went to use the oil press in Agios Ioannis which was owned by D. Saltaferos]

- #902. 7,116 – 07-12-1833 to 27-01-1834. Ledger of olive presses of: Salvara, Kokorou, Agiou Spyridonos, Kamaradou, Mitrou Saltaferou, Mposinaki, Manolou Manousaki, Church of Parori, Matala of Parori, Niarchou of Kato Chora, Prastaki, Trichaki… It is stated how much oil they extracted and how many oil bottles are for the tenth [the Ottoman tax].

- #1333. 12,12 – Chrysafa. 02-02-1838. Note. Note of Ioannis Mpalasaki (Chrysafa) to Antonis Salvara (Mystras), with which he sends him 2 tulums of oil 39 and 33 okades, a simple tithe, while he informs him that the rest of the shipment will be sent later. He asks if they took the pastoral tax. There is a note on the back page: 3 February 1828, I also received a load of oil from Chyrsafa okades 68.

- #572. 5,66 – Kastania, 19-06-1831. Letter from Anagnostis Tzortzaki (Kastania) to his son-in-law Antonis Salvaras (Mystras), whom he informs that he is sending him the cocoon of Perivolia. He complains about Saltaferos’ accusations and informs them that “we do not collect the tenths of the cocoons here, but let him find out that the machines are working and let the manager Saltaferos bark like a rabid dog.”

The Revolution of 1821 surely affected the Saltaferos businesses and family. The notary ledgers alone do not indicate the extent of impact, but entries during 1821-1830 denote numerous business transactions and concern about safety of the family.

- #138. 2,84 – Anapli [Nauplio], 02-08-1823 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Anapli) το Konstantine Salvara (Mystras). The problem of repairing the second pistol, the shipment of goods and a lot of family news are mentioned.

- #184. 2,130 – Niokastro, 25-02-1825 – Letter.

Letter from Ilia Kouskouri (Niokastro in Pylos) to Nikolaki C. Saltafero (Anapli), in which he informs him about the movements of Ibrahim Pasha, the destruction of Methoni, Koroni, Petalidi and the expectation of an attack on Niokastro. He is worried about the absence of Antonis Salvaras from Niokastro and assumes that he may be in Kalamata with the troops.

- #200. 2,146 – Nauplio, 02-07-1825 – Letter from Dimitri Saltaferou (Nauplio) to Antoni Salvara. Saltaferos and his wife deem it expedient to transport at least the women, perhaps the rest, to Nafplio and from there send them to another place for safety.

- #142. 2,88 – Anapli [Nauplio], 24-08-1823 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Anapli) το Anagnostaina Salvara (Mystras) Mentions the plan of the secret transport of their family from Mystras to Nauplio.

- #201. 2,147 – Nauplio, 09-07-1825 – Letter from Dimitri Saltaferou (Nauplio) to Antoni Salvara, in which Saltaferos insists on moving the family to Anapli [Nauplio].

- #242. 3,34 – Agina, 11-01-1827 – Letter. Letter from Michalis Karamitrou, Antonis Salvara and Ioannis Petropoulou (Aigina) to Mitro Saltafero and Konstantine Salvara. The former informs the latter that “we have reached the boss/master mills 21,200 grosia” and order them to “find and sell them to comrades” on the best possible terms. In a footnote, they inform about the good news in Distomo, where Karaiskakis “scolded” the Turks. On the back there is the next document.

- [Post-Revolution sale of land owned by Turks] #1287. 11,51 – Sparta. 09-09-1837. Contract Vineyard Sale. Sale of the vineyard of the mullah Sali Mpoyrakaki of Sklaviki (1 stremma, 280 meters with 7 olive roots and 4 figs) bought by M. Koutzis of Dimoprasia, instead of 310 drachmas, and gave it to one of his neighbors, Antonis Salvaras (also borders on Konstanti Mpakali, Lewnida Dimitrakaki and Nikolaos Saltaferos). Each year he will pay the market rate until it is repaid in 10 years. Guarantor: Michalis Koutzis. Witnesses: Konstantinos Pappakonstantopoulos, Ilias Karteroulis and Anagnostis Patrinakos.

It is always exciting to find references to families! Births, marriages and personal matters are mentioned in several extracts. The marriage between Dimitri Saltaferos and Anna Salvara could have either complicated or cemented the families’ business dealings–perhaps a bit of both. Either way, the union between these two powerful families would have been significant.

- Volume B, page 16, “Genealogy of the Salvara Family”: Anna Panagioti (Anagnosti) Salvara married in 1823 to the businessman Dimitri Chatzi Saltafero and lived in Nauplio. Anna died in 1837. Her olive grove in Pakota (Parori) was inherited by Antonis, Kanelitsa and Panagiotitsa [her siblings]. [My note: Pakota is a settlement in Agios Ioannis, not Parori.]

- #143. 2,89 – Nauplio, 02-09-1823 – Dowry Agreement; Detailed record of the dowries given to her daughter by Anagnostaina Salvara and to their sister from Konstantinos and Antonis Salvaras, due to her marriage to Dimitri Saltaferos. Two copies are saved.

- #159. 2,105 – Anapli [Nauplio], 04-03-1824 – Letter from Dimitri C. Saltaferou (Anapli) το K. Salvara (Mystras) refers to the receipt of “amantatiou” sent by Konstantine with Konstantine Leviodotis, and the announcement of the birth of twin boys.

- #926. 8,21 – Hydra, 13-04-1834. Letter from Dimitrios Ioannis Stavropoulou (Hydra) to Dimitrio Saltafero and Antonio and Konstantino Salvara (Mystras) in which he mentions a proposal made in Nauplio by friends and relatives for a match with their niece and the letter sent to him by their mutual friend Kyrillos about this issue and he replied that he would discuss with Anastasios Sigalos when he goes to Mystras. Now that Mr. Anastasios is going there, he will speak to them as his own man and may this match end positively.

The will of Konstantinos Salvara is so interesting to read. It confirms that Dimitrios (Mitros) Saltaferos is his son-in-law, provides for family members, and reveals his most important wishes.

- Will of Konstantinos Salavara, who is bedridden at the brothers’ house and dictates to S. Parthenopoulos, a notary of Sparta: transfers his property to his brother Antonios and orders him to give to each of his sisters Panagiotitsa, Kenelitsa, Anna 300 drachmas each. Regarding the debit bond, 2000 grosia, of Antoni Salvara, held by his son-in-law Mitros Saltaferos, he states that it has no force, because he intends to buy it in Konstantinople iron, which was sent to me with Maltziniotis’s nephew, but was blocked by Mitros himself because the revolution appeared, but the money was given to him by Konstantinos and he has proof. He also asks Antonis and his mother to make 3 contributions, to contribute 100 drachmas to the primary school, and when Saint-Spyridon is repaired, to contribute in order to preserve the name of the founders. He asks Antonis to do the right thing. Witnesses: Ioannis Th. Leopoulos, Ioannis Kokkonis, D. Manousakis, Athanasios Dimopoulos.

Finally, several entries reveal the community service rendered by the Saltaferos brothers. Next time I see the palm trees in Spartan villages, I will think of them.

- #487. 4,114 – Mystras, 28-10-1830. Payment receipt. Dimitris Saltaferos received from Antonis Salvara 996:67 palm trees for the second installment of the villages of Vamvakou, Arachova and Zarafona and 903:33 palm trees for the second half of the second installment of Vordonia.

I would love to read the original files and full documents, but the old Greek handwriting makes it impossible for me. To learn the details in these summaries would enliven these people and help me better understand everyday life during this momentous time in Greek history.

I express my deepest gratitude to Pepi Gavala for her ongoing work in publishing holdings of the Archives of Sparta. All of us must appreciate and be supportive of the efforts of the GAK offices to preserve and make available the documents which reflect the stories and times of our ancestors.

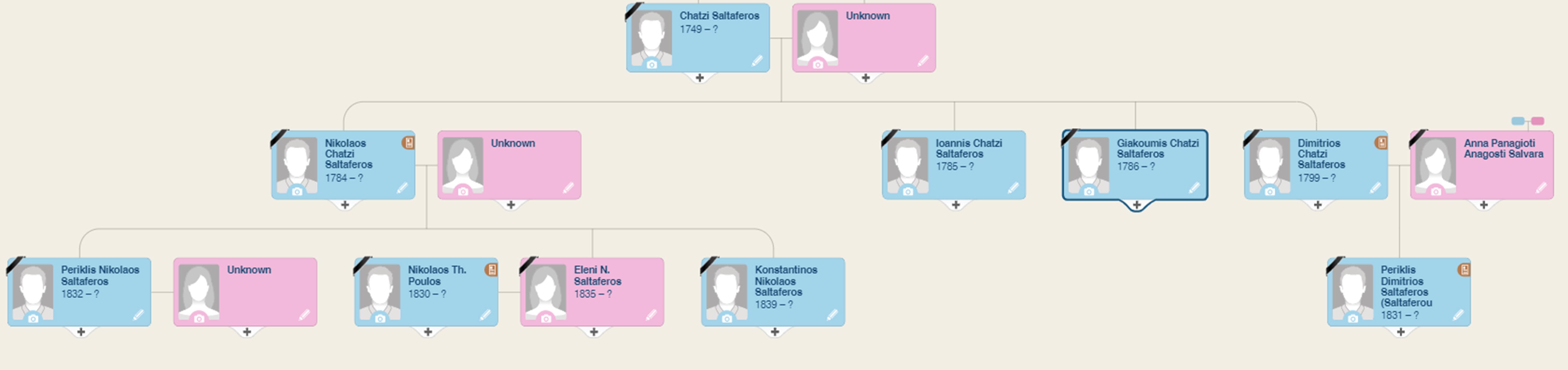

Family Tree of Chtazis Saltaferos (click on image to enlarge)

Chatzi Saltaferos Family Tree, March 2021

__________

[1] Γαβαλα, Πεπη, Αρχείο Δημητρίου Κ. Σαλβαρά, Αναλυτικό Ευρετηρίο, Τόμος Α, 1709-1831], Σπαρτη, 2001, Υπουργείο Εθνικής Παιλείας και Θρησκευματών, Γ.Α.Κ., Αρχεία Νομού Λακωνίας, Σπάρτη 23100.

Gavala, Pepi; Archives of Dimitrios K. Salvara, Notary, Detailed Index Volume A, 1709-1831; Sparta, 2001, Ministry of National Education and Religions, General State Archives of Greece – Archives of Lakonia

Γαβαλα, Πεπη, Αρχείο Δημητρίου Κ. Σαλβαρά, Αναλυτικό Ευρετηρίο, Τόμος Β, 1832-1843], Σπαρτη, 2001, Υπουργείο Εθνικής Παιλείας και Θρησκευματών, Γ.Α.Κ., Αρχεία Νομού Λακωνίας, Σπάρτη 23100.

Gavala, Pepi; Archives of Dimitrios K. Salvara, Notary, Detailed Index Volume B, 1832-1843; Sparta, 2001, Ministry of National Education and Religions, General State Archives of Greece – Archives of Lakonia

[2] Volume B is downloadable in pdf from GAK Lakonia website: http://gak.lak.sch.gr/Actvt/actvt-Pub_salvaras-b.pdf

[3] Chatzi is not his baptismal name; it is a nickname indicating he had made a pilgrimage.(Gregory Kontos to Carol Kostakos Petranek, October 10, 2020.) Two of Chatzi’s sons named their first sons Perikles, and according to naming traditions, I assume that may be Chatzi’s baptismal name.