Notary files in archive offices contain gems of information about families, businsess dealings, and traditions. People who entered into contracts–whether for dowries, businesses, or loans–ensured that the contract was legally binding by signing before a notary and witnesses. At the Sparta, Lakonia office of the General State Archives of Greece, Gregory Kontos and I found several notary files of great interest to me which documented transations by my ancestral family.

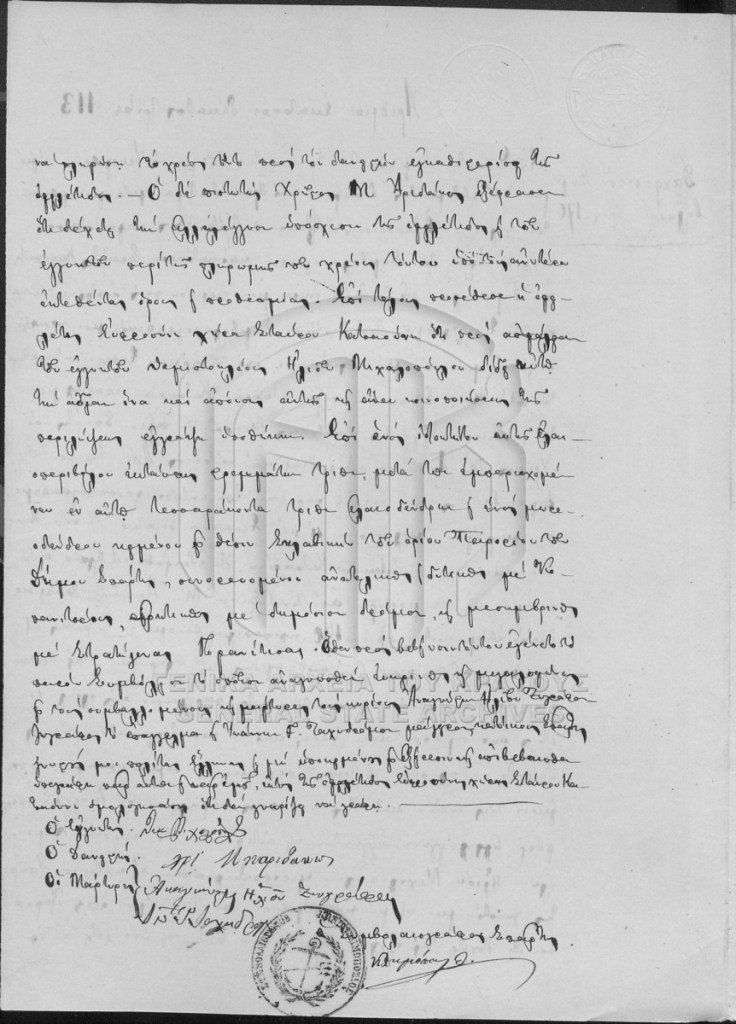

This is one of those notary documents. My great-grand uncle, Christos Aridakos (Aridas) entered into a contract to loan money to Ephrosyni Stasinakis. The document is dated December 30, 1863. The details are fascinating! This translation was done by Gregory Kontos.

Lending contract between Christos Aridakos and Ephrosyni Stasinakis, 12/30/1863

(page 1)

In Sparta, today, on the 30th of month December, day Monday, and at 2pm, of year 1863, Ephrosyni, daughter of the late Konstantinos Stasinakis and widow of Stavros Katsaounis, housekeeper and resident of Mystras of the Municipality of Sparta, and Christos M. Aridakos, landowner and resident of Agios Ioannis of the Municipality of Sparta, both known to me and legal people, appeared before me, notary and resident of Sparta, Konstantinos Dimopoulos, at my notarial office, located at my house which is at the east of the Church of the Annunciation of Theotokos. In the presence of the witnesses signing below they stated the following: Ephrosyni, daughter of the late Konstantinos Stasinakis and widow of Stavros Katsaounis, declared that she borrowed and got, before me and the witnesses, 170 drachmas from Christos M. Aridakos, including their interest until the expiration of the payment, and promises to return this money to him after the lapse of one whole year from this day without any interest. In case of a deferred payment, she promises to pay an agreed interest of 20% per year; and in order for the lender to be secure, she adds Themistocles Ilia Michalopoulos, merchant-landowner and resident of Sparta, present, known to me and legal, as a joint and several guarantor. He (Themistocles) stated that he accepts this guarantee of the debtor and promised

(page 2)

to pay this debt to the lender. On the other hand, the creditor, Christos M. Aridakos, declared that he accepts the promises of the debtor and the guarantor to pay this debt under the above mentioned terms and deadlines. Lastly, the debtor, Ephrosyni, widow of Stavros Katsaounis, added that in order for the guarantor, Themistocles Ilia Michalopoulos, to be secure she gives him the permission to mortgage an olive grove of herself, 3 acres big, together with the 43 olive trees in it and a […]tree, located at the place “Sklaviki” at the borders of Parori of the Municipality of Sparta; on the east and west side the field is adjacent to the Koumanitoros family, on the north side to a public road and on the south side to Stratigena Goranitissa. And as an indication was the present agreement contract created, which, after being read sufficiently and loudly before the stipulators and the witnesses, Mr. Anagnostis Ilia Zografos, painter, and Ioannis G. Tahydromos, cook, residents of Sparta and Greek citizens known to me, and after being confirmed, was signed by them and by me, except for the debtor, Ephrosyni, widow of Stavros Katsaounis, who claimed she’s illiterate.

The guarantor, Them. Michalopoulos

The lender, Chri. M. Aridakos

The witnesses: Anagnostis Ilia Zografos; Io. G. Tahydromos

The notary of Sparta, K. Dimopoulos

(page 3)

[…] It is requested from every bailiff to execute the present contract, and from every attorney to do his duty, and from all the judges and public officials to help, if they’re legally asked to.

[…] In Sparta, July 7th 1866.

The notary of Sparta, K. Dimopoulos

Source: General Archives of Greece, GAK Lakonia, Sparta Office

Notary: Konstandinos Dimopoulos, Volume: 12.1.1

Contract Reference Number: 113/31.12.1863 (Contract #113; date: 31 December 1863)

Accessed July 2014; Carol Kostakos Petranek & Gregory Kontos