by Panagiotis K. Kourtalis

published in The Faris Newsletter Issue 81, January 2025, page 3-6

“The dowry of a poor house is the whitewashed walls,” says a folk proverb, which is absolutely accurate if we consider that in the agrarian societies of our villages in the past, luxurious means of beauty were entirely absent, lime—also called “choringki”—was for many years the mark of nobility and proof of τhe tidiness and absolute cleanliness of a household.

At the same time, lime, along with sulfur, was one of the few products available to ordinary people for systematically disinfecting spaces such as courtyards, terraces, pens, trenches, henhouses, kitchens, latrines, and animal stables in times when dangerous infectious diseases such as typhoid, tuberculosis, echinococcosis, and hemorrhagic fever decimated both people and animals.

Lime, of course, was used, as it is today, primarily in construction of walls with stones, adobe, bricks and cement blocks, for plastering (coating) built surfaces, and for painting the surroundings, facades and rooms of houses with the so-called “whitewashes.”

Whitewashes were the paints used instead of today’s plastic paints and were produced either by diluting slaked lime with water for simple whitewashing of walls, courtyards, pens, and terraces, etc., or by diluting slaked lime with water and adding special color pigments, known as “ochres,” to create different shades for painting walls and rooms.

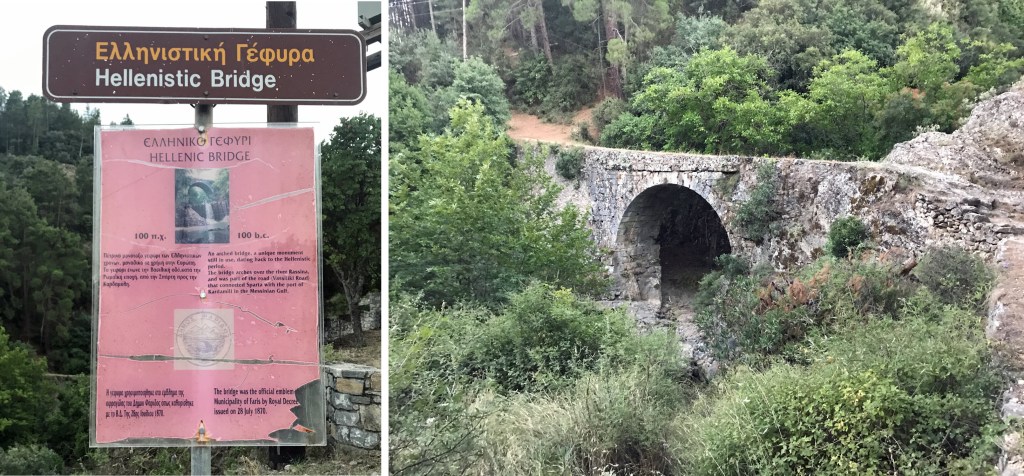

The basis for all this was the so-called “quicklime,” meaning the powdered lime produced by lime-makers in the spring in special outdoor kilns called lime kilns “kaminia” known as asvestokamina. As fuel, all lime kilns primarily used wood cut from olive and oak trees, known as “koutoukia,” and bundles of holly and sunflower branches, which were abundant in the forests and fields, especially after pruning season. Lime kilns were built in areas where the two essential raw materials for lime production, limestone and fuel.

The lime makers, after selecting a suitable location, dug a large pit and built its walls with limestone in successive layers, taking the form of a dome with an opening in its lower part for the supply of fuel. The lower layers of the kiln were built with river stones, while the upper layers were made with marble stones and clay. The river stones [3] were extracted from the streams of our region (e.g., Rasina, Kolopana), while the marble stones [4] were extracted from quarries using chisels, hammers, crowbars, or sledgehammers (e.g., Komninos’ quarry, above the reservoir of Xirokampi). Most kilns in the area were built near the Kolopana stream, hence the name Kaminia of the village, but also next to the Rasina stream in Xirokampi, below the forested area of Barbanitsa, such as the lime kiln of Feggaras.

The temperature generated by the burning fuel inside the kiln dome could reach up to 2000 Celsius degrees, converting almost all the stones into lime. The kiln fire was typically ignited at dawn, and the burning process had to continue uninterrupted for at least 24 to 48 hours, or even longer, if necessary, to ensure that the high temperature fully calcificate most of the stones. After burning, the kiln needed another day to cool down. Then, the workers, who had taken shifts monitoring the fire and constantly feeding it, would carefully enter the kiln and clean the lime. The workers would remove the residues of fuel and stone, then package the lime into linen sacks (linatses),[5] which usually held one kantari, meaning 44 okas of lime.

From the family expense ledger of Vasileios S. Christopoulos, we learn that in the year 1900, “choringki from Giorginas Dogantzos, ten kantaria,” meaning 440 okas of unslaked lime (in raw form), cost the family 22 drachmas.[6] If we do the calculation carefully, this means it was purchased at 5 lepta per oka.[7]

The lime was delivered to homes or to the construction site of a building in the 44-okas linen sacks mentioned above, with animals (donkeys, horses, mules), horse-drawn carts or trucks. In newly constructed buildings, along with the foundations and the cistern of the house, a large pit was dug in the yard, called a choringkogouva. In the choringkogouva, the powder with the quicklime was emptied and filled with water so the lime could “slake” and and turn into a slurry. The process was very dangerous because, when the powder came into contact with the water, it slowly foamed, produced intense fumes, and could cause fatal burns to anyone who touched or inhaled it. That is why they surrounded the choringkogouves (sluice gates) with wire and forbade children and the elderly from approaching due to the deadly danger of tripping and falling inside. In the desperate verse of the love-struck young man that follows, we clearly discern this danger:

Big pit (choringkogouva)

I will open in your yard

to fall inside

to burn

to extinguish from your life.

With slaked lime, copper sulfate and water, farmers also prepared the Bordigal slurry, a fungicidal pesticide, with which they sprayed to combat downy mildew on vines, potatoes and other plants, rust and anthracnose on figs and pears, and diseases on oranges and olives.

In our villages, it was established and fortunately remains to this day the traditional custom of cleaning and whitewashing the courtyards of houses and churches during Holy Week in preparation for the great feast of Easter. The housewives took care to write phrases with chalk on the ground with the usual wishes of the days (days (HAPPY HOLIDAYS, HAPPY EASTER, HAPPY RESURRECTION) and to draw figures representing white candles and Easter eggs. Families with recent bereavement were exempt from the Easter whitewashing, since according to the proverb: “without whitewashing in the courtyard, Lambri is sad.”

Today, due to the development of technology, open-air lime kilns, traditional lime makers and choringkogouves no longer exist. Lime is mass-produced and marketed by specialized industries in its two traditional forms, namely: a) in powder, which is used in crops as a soil improver and is usually packed in nylon bags and b) in paste, which is used as a building material and is usually packed in transparent nylon bags with special handles, so that, due to its caustic nature, contact with human skin is avoided.

Notes:

- The text that follows is based on the narratives of my late grandparents Nikonas D. Dimitrakopoulos, Georgios K. Kourtalis, and my grandmother Marigo N. Dimitrakopoulou, née Efstratios Orfanakos, residents of Xirokampi, which I recorded as a young student in a school notebook in April 1987. See also I Pharis 51 (2010), pp. 5-7.

- Copper cauldron

- River stones: White limestone rocks

- Marble stones: Gray limestone rocks

- Linen sacks: Large woven sacks made from flax fibers.

- See Vasileios I. Christopoulos, The Expenses of a Family at the Beginning of Our Century, I Pharis 17 (1997), p. 5.

- The okka (Turkish: okka) was a unit of mass measurement used in Greece until 1958, when it was replaced by the kilogram. One okka equaled 400 drams and corresponded to 1,282 grams, while one kantari equaled 44 okkas, or 56.4 kilograms today.

I (Carol Kostakos Petranek) am honored to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the twenty-first article of the ongoing series. Previous articles can be viewed here.