Family challenges often lead to difficult decisions. Among the most heart rending are those involving minor children. Parents die or become indigent, leaving their most vulnerable loved ones to be cared for by others–perhaps family members, perhaps not.

My mother shared such a story about her Uncle Kolokota and his wife, Katina (whom mom called Thea Kolokotou). “They never had children of their own,” she said. “Instead, they raised their niece. Thea Kolokotou’s sister and her husband had nine children, born two years apart. They couldn’t take care of them all, so Theo and Thea took in one of the daughters and raised her as their own.” I remember being mildly surprised, yet reassured, that this couple would open their home and hearts to help one of Katina’s children. This was my first introduction to ψυχοπαίδια (psychopedia), known in Greece as “soul children1.”

naturalization photo, 1937

My grandfather, John Andrew Kostakos, was the youngest of eleven children. When he was about one year old, his mother died. I learned stories of him being nursed and cared for by women in the village while his father worked in his fields. Then John’s father died when he was eight years old, and John was taken in and raised by his half-brother, Gregory, who had five children of his own. At age 14, John left Gregory’s home to work for a wealthy man in Mystras, who funded John’s voyage to America.

naturalization photo, 1931

The concept of an orphaned child being raised by family members is repeated in countless families.

The concept of a child whose parents are unable to care for him/her, then is raised by family members, is less common.

What is rare, but not uncommon in rural Greece, is the concept of an orphaned or destitute child who is not formally adopted, but is brought as a “soul child” into the home of an unrelated family.

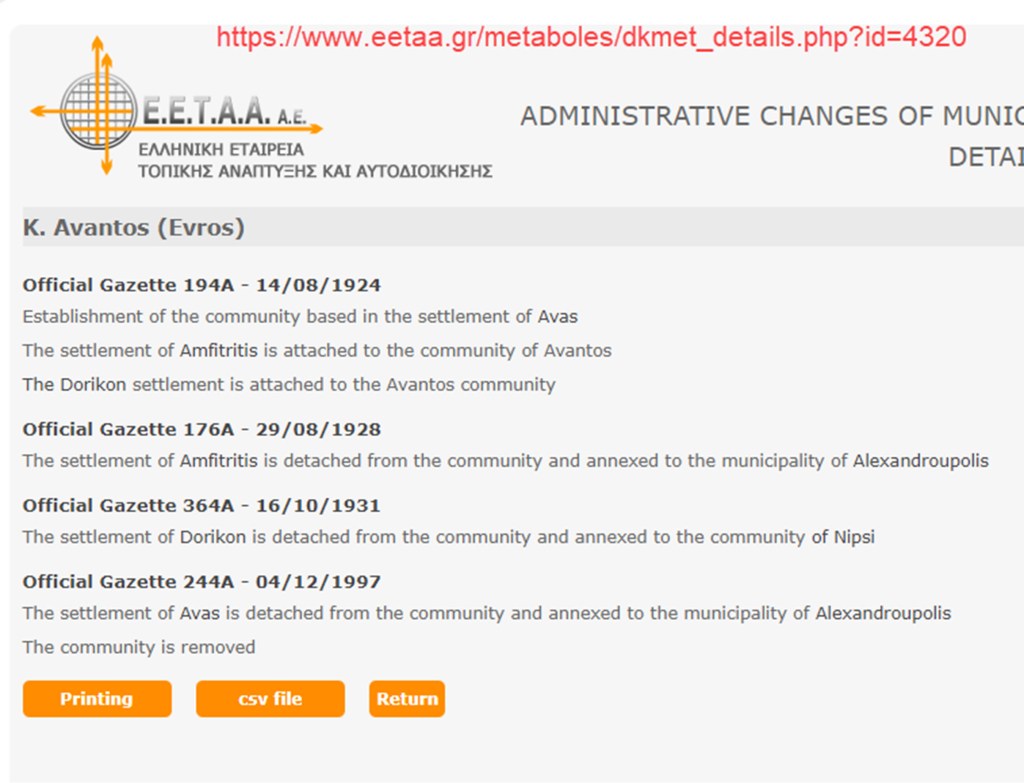

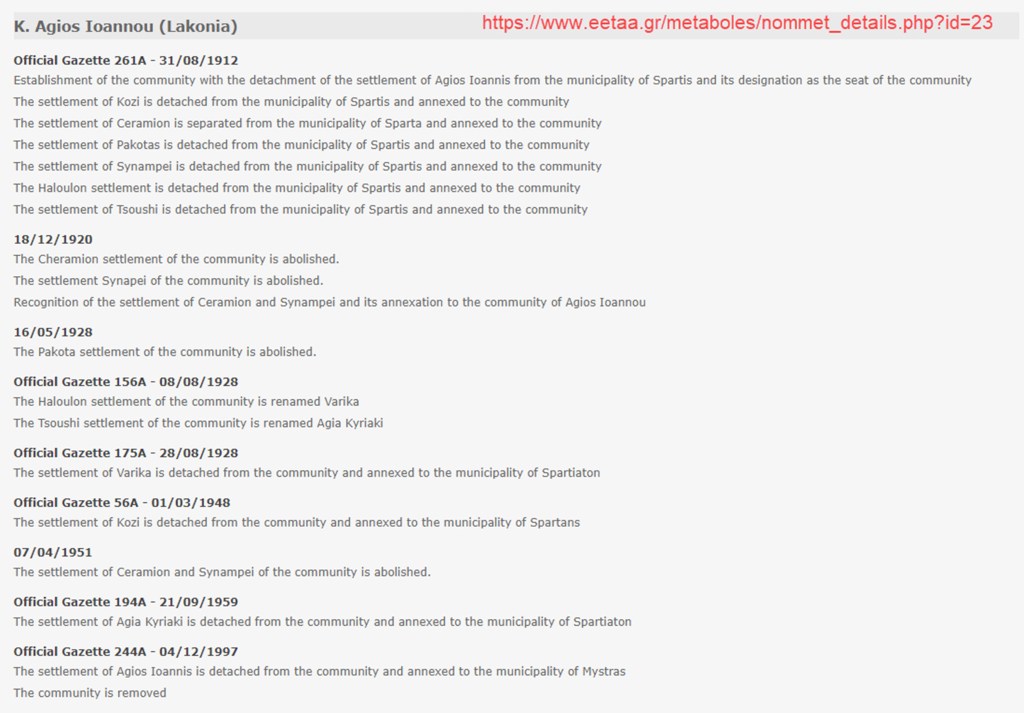

I found such a case this week, as I was adding marriage records into the family tree I am creating for the village of Agios Ioannis, Sparta.2

Year: 1875, Entries: 205-216 Entry #209

I began entering information for entry #209:

Marriage License Date: August 24, 1875

Groom: Nikolaos Voulgaris of Agios Ioannis

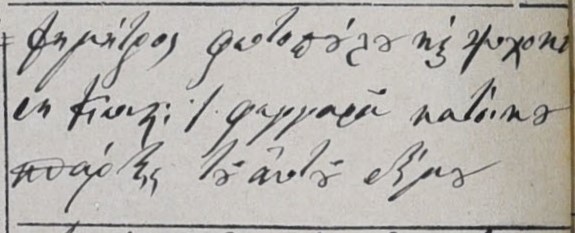

I then saw an unusual entry in the bride’s column. Normally, the entry would give the name of the bride, her father’s name, and residence. But this entry reads: Dimitro Fotopoulou, psychokori Konst. I. Feggara, residence, Sparta.

I was stumped as to why Dimitro’s father’s name was not recorded in her marriage record. And who was Konstantinos Feggaras? I sent the image above to my colleague, Gregory Kontos, owner of GreekAncestry. He responded that Fotopoulos was her biological father’s surname, and that Konstantinos I. Feggaras had “adopted” her. Greg reminded me that Greek Ancestry had published this article, “Soul-children” (Ψυχοπαίδια) earlier this year.

An excerpt from the article: The term “soul – child” describes an institution already existing in Byzantine customary law. According to this, the “soul – son” or the “soul – daughter” are granted to the “soul – parent”, who in exchange for the child’s labor undertakes the obligation to ensure his professional development or endow her until she reaches the age of marriage. In comparison to an ordinary adoption, the tradition of the “soul – children” was accompanied by a less formal legal relationship, and by a strong ethical character, which is also reflected by the first part [“ψυχή” (soul)] of this Greek compound word [“ψυχή” + “παιδί” (soul + child)]: this signifies the moral and religious attitude of the father, who aims not only at his inner atonement but also at the devotion of the adopted child to him during the last years of his life. The benefits from the offered labor usually were not important.

Reading this description, we see that ψυχοπαιδία/psychopedia connotes a deep and loving relationship–one that would rival, if not equal, that of biological parents and children. A legal adoption may have been difficult, and honestly, not necessary, in rural Greece. That this practice was brought to America and followed by the Kolokotas’ and other families gives us a heartwarming insight into those who welcomed children of need into their homes.

1For a detailed historical description and case study of this topic, see “Soul-Children (Ψυχοπαίδια)” published by GreekAncestry on March 14, 2023.

2MyHeritage has a collection titled, Sparta Marriages, 1835-1935, which I digitized at the Metropolis of Sparta. This collection has both the marriage index books and accompanying marriage licenses for thousands of families.