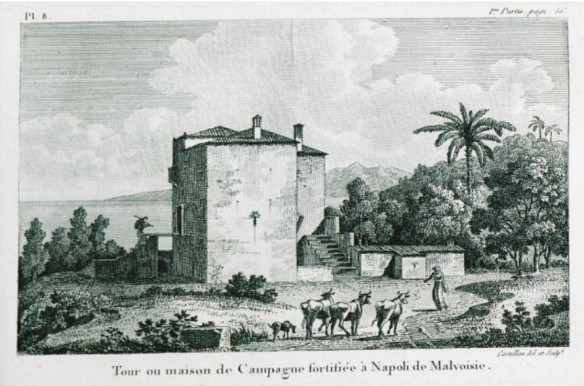

From the 12th to 18th centuries, the Venetians controlled a large empire which included parts of Greece. As the Ottomans expanded their conquests in the 14th century, it was inevitable that conflicts between the two empires would arise in the eastern Mediterranean. Indeed, seven wars, the first in beginning in 1463 and the seventh ending in 1718, erupted. Greece was caught in the crosshairs and endured a series of conquests from these two powers.

The Venetians ruled from 1685-1715, between the first period of Ottoman occupation (1580-1685) and the second (1715-1821). The successful military strategies of General Francesco Morosini brought the Peloponnese and other areas of Greece under Venetian domination. The Peloponnese, known then as the Kingdom of Morea, was divided into four districts (Messenia, Achaia, Lakonia, Romania now the region of Corinth) and within them were twenty-six territories. The entire Peloponnese in 1700 had only fifteen towns/cities with 1,000 or more inhabitants[1] and among these was Mystras.

While reading historian Evangelia Balta’s informative essay, Venetians and Ottomans in the Southeast Peloponnese, 15th-18th century[2], I came across an interesting paragraph referencing Mystras: ”In the Venetian archives there are lists of inhabitants of the wider region of Mystras, who were conscripted in 1698 to work on the fortification works at the Isthmus of Corinth. These lists mention the number of persons that each village in the districts of Mystras, Elous and Chrysapha should provide for the corvee[3]. In the event of someone escaping, the elders of the village were obliged to pay six reals.[4]”

Historical essays on the Peloponnese during its period of Venetian rule often cite documents held at the Venetian Archives. Balta explains the importance of this repository: “ If we have an idea of the settlement pattern and the population of the Peloponnese prior to the Greek War of Independence, we owe this to the published Venetian registers of the late seventeenth century.”[5]

Therefore, I was very excited to learn about the research trip to the Venetian Archives recently undertaken by researcher Nick Santas. He will be speaking about this experience at the 2nd International Greek Ancestry Conference to be held next weekend, January 29-30. Nick describes his session: The Kingdom of Morea Archives collection covers the period of the second Venetian conquest of the Peloponnese (1685-1715). It has been the subject of historical research in the past, but has had very limited genealogical examination. During this session, Nick aims to share his findings with you, help you familiarise yourself with the practical steps when accessing the archives, and give you a taste of what is available.

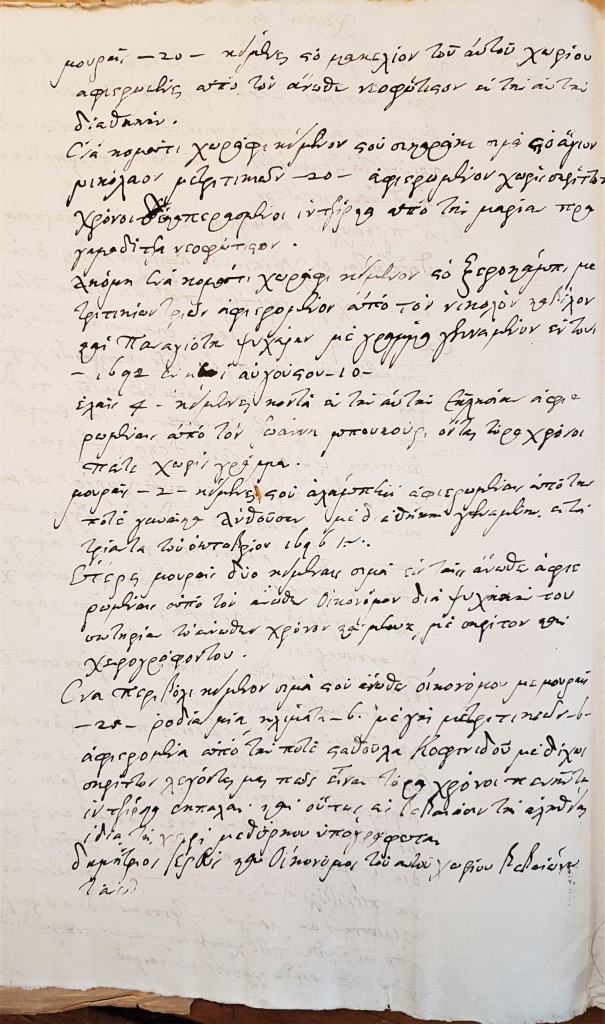

I was thrilled when Nick sent me the following Venetian Archive document from my village of Agios Ioannis, Sparta (Ayiannis). He also (thankfully) provided a translation. I am extremely grateful for Nick’s thoughtfulness in sending me this document, and for his generous expenditure of time in making the translations, first into modern Greek, then into English.

These historical records bring the past into the present and provide us with invaluable facts about the past. Every one brings us one step closer to understanding our history and our ancestors’ lives.

TRANSLATION: Village of Ai Yiannis

On May 16, 1699 in Mistras, appeared Mr. Demetrios Priest and Rector of the church of Virgin Mary located in this village (Ai Yiannis), who under oath made known the standing dedications.

First, a yard around the said church, where the Christians are buried, dedicated in years gone by without a document (σκρίττον from the Italian scritto) which no one can recollect

Nearby, there is a place dedicated in years gone by, without a letter. The house (on this land) was built and dedicated to the church by Ioannikios, approximately (ιντζίρκα from the Iltalian incirca) 10 years ago

An orchard lying in the said village with 20 Mulberry trees, 18 fig trees, 12 pomegranates, 20 wild trees with their vines, 6 metritikion in size from Panagiotis Stamatopoulos, approximately 9 years ago with a letter made on 6 January 1690

Near the above church, there is a salad garden, one metritikion (μετρητίκιον) in size dedicated in years gone by without a document, not knowing how many years

A house with a floor, lying inside the said village dedicated by Giorgos Chatzakis a (religious) convert, with a will made on 28 February 1692 for his memorial service (δια μνημόσυνον)

An orchard near the above house lying with 13 mulberry trees, 10 vines and land of 2 metritikion dedicated from the said late Chatzakis with a will

20 Mulberries lying at the [….] of the same village dedicated by the above convert in the same will

One field lying at Sikaraki (Συκαράκι) near St. Nicholas 20 metritikia, dedicated without a document approximately 10 years ago by Maria Pragamaditza, convert

Another field lying at ‘Xerokampi’ (Ξεροκάμπι) three metritikia dedicated by Nikolos Kavilos kai Panagiotis Psicharis by letter written on 10 August 1692

4 olive trees lying near the said church dedicated from Ioannis Boukouris 5 years now, without a letter

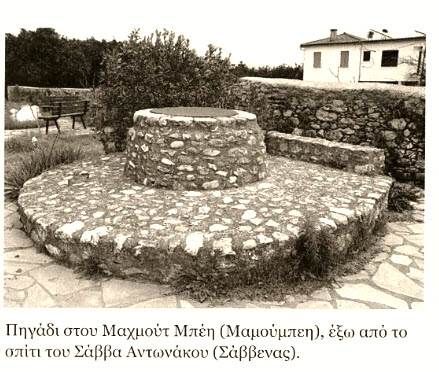

2 mulberries lying at ‘Alambei’ (Αλάμπεη) dedicated from the late Anthousa by will made on 30 October 1696

Another 2 mulberries lying near the above ones dedicated from the above Rector for the salvation of his soul with a document

An orchard lying near the above Rectors’ with 25 mulberries, one pomegranate, 6 vines and 6 metritikia land, dedicated from the late Stathoula Kofinidou without a document approximately 50 years ago

For the truthfulness of the above He signs with his own hand

Demetrios Priest and Rector of the said village

TRANSLATION: Greek

Χωρίον Αγιάννης

1699 μηνί μαϊου 16 μιστρά ανεφάνη ο παπα κυρ δημήτριος και Οικονόμος ευφημέριος της Εκκλησίας της Κυρίας Θεοτόκου κυμένης στο χωρίον το αυτό, ο οποίος μεθόρκου φανερώνι τα στεκούμενα, οπού τινα αφιερωμένα από το καθένα, πρώτον

Ένα προαύλιον εν τω γύρο τη αυτή εκκλησία, οπού θάπτωνται οι Χριστιανοί αφιερομένος ο αυτός τόπος έκπαλαι χωρίς σκρίττον που δεν θυμούνται.

Εκεί σιμά ευρίσκετον εις την εκκλησίαν ένας τόπος αφιερωμένος από τον καιρόν των παλλαιών χωρίς γράμμα και ήτον ο αυτός τόπος μόνον τη αυτή. το δε σπήτι το έκτισεν και το αφιέρωσεν ει την εκκλησία κάποιος Ιωαννίκιος τρέχουν χρόνοι δέκα ιντζίρκα –

Ένα περιβόλι κύμενον στο αυτό χωρίον με μουραίς 20 – συκαίς 18 – ροδαίς – 12 – δένδρα άγρια μετά κληματά των – 20 – μετριτικιών γή – 6 – αφιερομένον από τον παναγιότην σταματόπουλον όντας χρόνοι εννία ιντζίρκα με γράμμα γεννομένον 1690 εν μηνί 6 Ιαννουαρίου.

Σιμά εις την άνωθεν εκκλησία ευρίσκεται ένας κήπος σαλατικών μετριτικιού ενός αφιερωμένον έκπαλαι χωρίς σκρίττον δεν ιξεύροντας πόσοι χρόνοι να είναι

Ένα σπήτι πατομένον κύμενον μέσα στο αυτό χωρίον αφιερωμένον από τον Γιώργον Χατχάκη νεοφώτιστος με διαθήκη γεναμένη 1692 εν μηνί 28 φευρουαρίου δια μνημοσυνον του όντας το άνωθε σπήτι με την αυλήν του

Ένα περιβόλι σιμά στο άνωθε σπήτι κύμενον με μουραις 13, κλίματα -10- και γη μετριτικιών δύο αφιερωμένης από τον άνωθε ποτέ Χατζάκη νεοφώτιστον με διαθήκη μοδηρική εις τον άνωθεν χρόνον και καιρόν

Μουραίς – 20 – κύμενες στο μακελίον του αυτού χωρίου αφιερωμένες από τον άνωθεν νεοφώτιστον εις την αυτήν διαθήκην.

Ένα κομάτι χωράφι κύμενον στου σικαράκη σιμά στο άγιον νικόλαον μετριτικιών – 20 – αφιερωμένον χωρίς σκρίττον χρόνοι δέκα περασμένοι ιντζίρκα από την μαρίαν πραγαμαδίτζα νεοφώτιστον.

Ακόμη ένα κομάτι χωράφι κύμενον στο ξεροκάμπι, μετριτικίων τριών αφιερομένον από τον νικολόν καβίλον και Παναγιώτη ψυχάρην με γράμμα γεναμένον εν τους 1692 εν μηνί αυγούστου – 10 –

Ελαίς 4 – κύμενες κοντά εν την αυτήν εκλησίαν αφιερωμέναις από τον ιωάννη μπουκούρι όντας τόρα χρόνοι πέντε χωρίς γράμμα.

Μουραίς – 2 – κύμενες στου αλάμπεη αφιερωμέναις από την ποτέ γυναίκα ανθούση με διαθήκη γενάμενη εν τη τριάντα του οκτοβρίου 1696 i.v.

Έτερες μουραίς δύο κύμεναις σιμά εις ταις άνωθε αφιερωμέναις από τον άνωθε Οικονόμο δια ψυχηκή του σωτηρία το άνωθεν χρόνον και μηνί με σκρίτον και χειρογράφοντου.

Ένα περιβόλι κύμενον σιμά στου άνωθεν οικονόμου με μουραίς – 25 – ροδιά μια, κλίματα – 6 με γη μετριτικιών – 6 – αφιερομένα από την ποτέ σταθούλα Κοφινιδού με δίχως σκρίττον λεγοντας μας πως είναι τόρα χρόνοι πενήντα ιντζίρκα εκπαλαι και ούτως ει βεβαιώσιν της αληθίας ιδία τη χειρί μεθόρκου υπογράφεται

Δημήτριος Ιερεύς και Οικονόμος του αυτού χωρίου βεβαιώνω τα

__________

[1] As documented by the Grimani Census taken in 1700. The Venetians appointed Giacomo Corner as the governor-general of the Morea. He commissioned Francesco Grimani to undertake the census.

[2] Balta, Evangelia. Venetians and Ottomans in the Southeast Peloponnese, 15th-18th century

[3] Unpaid labor (as toward constructing roads) due from a feudal vassal to his lord; labor exacted in lieu of taxes by public authorities especially for highway construction or repair. Source: Merriam-Webster online dictionary.

[4] Silver coins of Spanish origin in the 1500s; their value was based on free market values of gold and silver. Tezcan, Baki. “The Ottoman Monetary Crisis of 1585 Revisited,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 52, No. 3 (2009), pp. 460-504 (45 pages); accessed from JSTOR on January 23, 2022.

[5] Balta, Evangelia. Venetians and Ottomans in the Southeast Peloponnese, 15th-18th century, p. 270