Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Today, June 4, is the celebration of Pentecost, an important holiday in the Christian religion and a great feast in the Orthodox Church. It is celebrated fifty days after Easter and gets its name from that number (pente / πέντε). It commemorates the day the Holy Spirit descended on the apostles in Jerusalem, after which they were able to speak in tongues.

This morning my cousins took me to church services to one of the most important Byzantine monasteries in Lakonia, the Monastery of the Holy 40 Martyrs (Ιερα Μονη Αγιων Τεσσαρακοντα Μαρτυρων). The monastery takes its name from The Forty Martyrs of Sebaste. They were Roman soldiers who, in the year 320, were killed for not renouncing their Christian faith.1 Located by the village of Chrysafa, about 5 miles from Sparta, the Monastery is near the top of a mountain, surrounded by fields and olive trees. The original monastery was in a natural cave, initially founded in 1305 and situated northeast of its present location. It was moved to its present location in the 17th century.

Over time, stone buildings were constructed and the complex grew to meet the needs of an increasing number of monks and priests.

The Metropolis of Sparta designates the interior frescoes as “a miracle of Byzantine painting reaching the limits of high art.1” Painted against stone, their colors have remained vibrant throughout the centuries. Tiny windows filter the light to make the interior ethereal.

During the Ottoman dominion of Greece, the sultan issued a decree which granted the Monastery special privileges and kept it from Muslim desecration. Also, the Monastery possessed a document, Achtanames (testament) of Mohammed, which granted the clergy freedom to practice the Orthodox religion, exempted them from taxes and military duty, and ordered the Muslims to shield them from those who would do harm.2 It was an extraordinary document which ensured the preservation of the Monastery and the protection of its monks and priests.

The importance of the Orthodox Church in Greece cannot be understated. It is not simply a religion, but is a significant source of Greek identity–especially during periods of foreign occupation. Through thousands of years, it has been a driving force in preserving Greek culture, language and history. Its libraries hold manuscript codices and documents of historical value. It operates schools and seminaries, and provides social services such as hospitals, orphanages, and charitable organizations.

The Church played a pivotal role in the Greek Revolution of 1821. It fostered patriotism and unity among the citizens, as well as providing them moral support and spiritual guidance. Priests not only encouraged the fight for liberation, but also fought side-by-side with revolutionaries. Monasteries and churches became hospitals or military headquarters, and sources of income to meet the needs of the armies.

To understand Greeks, we must understand their country’s ties to the Church, its significance in the history of the country, and its role in the everyday lives of its people.

1Orthodox Wiki

2Source of historical information: Metropolis of Sparta and Momenvasia

Around the time of the Greek Revolution of 1821, seven brothers left Crete and traveled to the Peloponnese. They scattered and settled in various areas. Three found their new home in a village 7 km north of Sparta, and the Zacharakis family of Theologos was formed. Theologos is situated 5 km straight up to the top of a mountain. Due to its height and spectacular views, the village is known as “the balcony of Lakonia.”

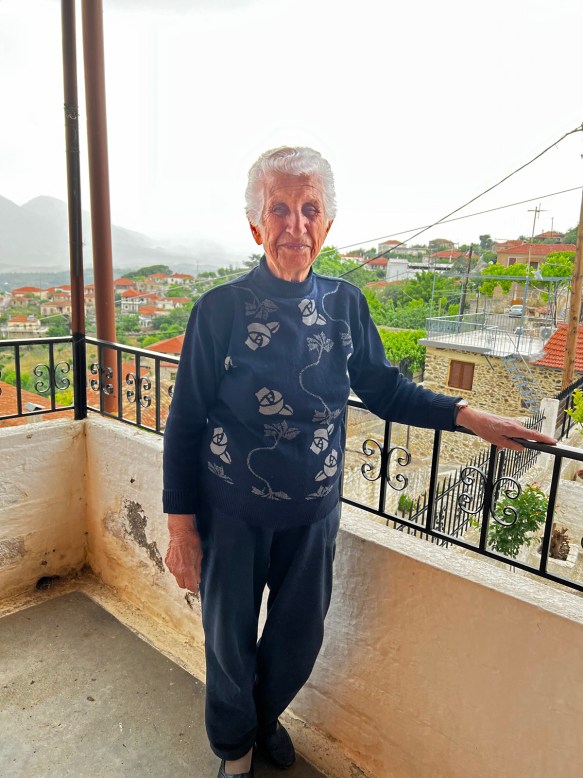

My great-great grandfather, Dimitrios Zacharakis, was among the earliest born in the village, circa1832. What type of life did he and his descendants experience? What were their occupations and their traditions? I asked my cousins to introduce me to the oldest member of the family, Georgia Zacharakis. At 93 years old, she is strong, sharp and sprightly. She continues to maintain the sprawling 100-year-old stone house that she shared with her husband (now deceased), Ioannis Athanasios Dariotis.

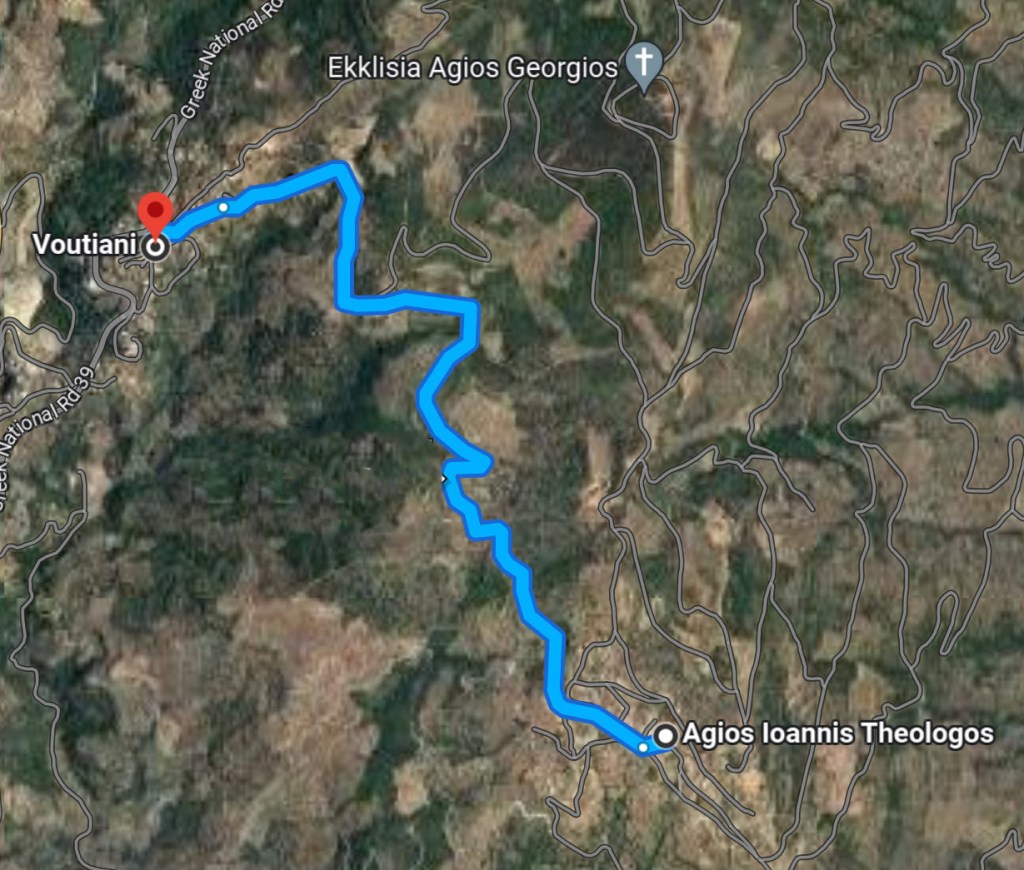

Through her reminisces, Georgia brought the past into the present. Village life was as rugged as its mountain. Transportation was by horse or donkey. It was not until 1970 that a narrow, switchback, paved road to Theologos was constructed. Prior to then, people rode animals or walked 4 km over winding mountain paths to the nearby village of Voutiani which had the only road on the mountain. It led to the city of Sparta where people could shop, conduct business, and access doctors or government facilities. There, horses and donkeys were kept in a χάνι (chani), a house with a large inner courtyard, where travelers and their animals camped and spent the night.1 After returning to Voutiani, people walked the 4 km back to Theologos, and this time their animals — or their arms — were laden with the goods and items purchased. The return trip was all uphill and done barefoot. Shoes were a luxury, not a necessity.

Homes were built of stone and, until recently, had no modern conveniences. Nestled in the cliffs, steep steps led to every house.

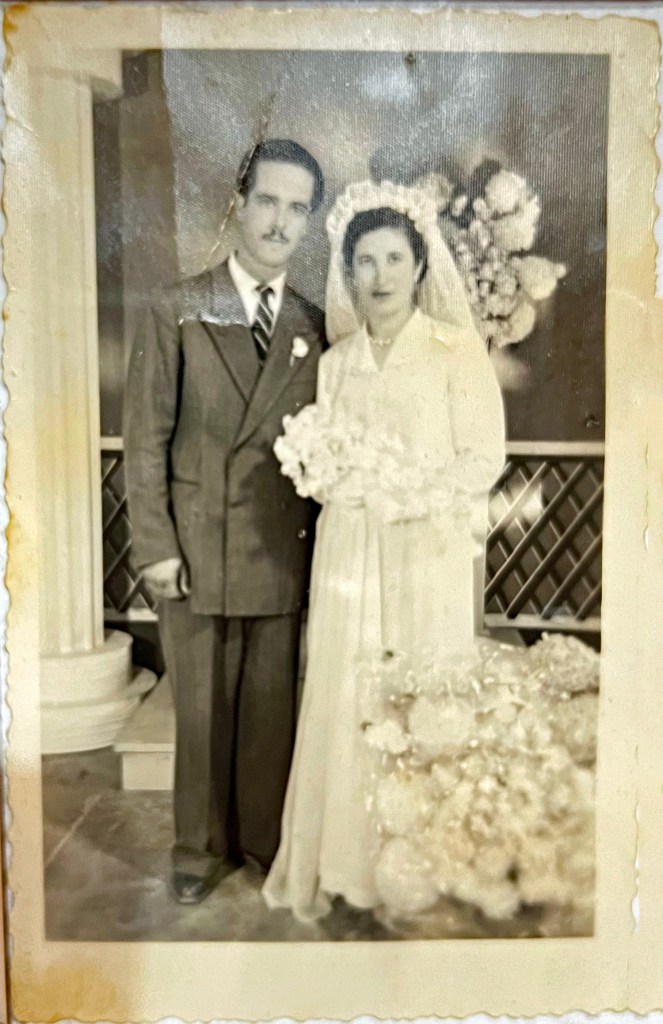

Village families were very close and considered themselves one unit. Because they knew each other well, marriages among their children did not present unexpected surprises such as alcoholism, illness or mistreatment of spouse or children. Marriages were arranged by a matchmaker (either male or female), who received money for their services. Georgia said, with a sparkle in her eyes, that although match with a man from Agios Ioannis, Sparta was being considered for her, she refused it — preferring a man from Theologos. She married Ioannis Dariotis in 1953.

Both men and women labored ceaselessly. The primary occupation was growing olives. For a time, only about ten families owned all the olive trees that fill the mountainside of Theologos. The rest of the men were laborers, working in the groves. As time passed, almost every family eventually owned at least one grove. Olive oil production was such a large business that two processing plants were built; currently, neither is operational. The villagers now bring their olives into Sparta for processing. Even today, the olive harvest season is long, lasting from October to April, because of the large amount of olives grown on the mountain.

A few village men were woodworkers and carpenters or stone masons. Every building is constructed of stone, hewn from the mountain. Georgia’s father, Nikolaos, was a woodworker. Her husband, Ioannis, did not have an occupation when they married, and he worked with Nikolaos to learn the woodworking trade. Ioannis’ father was a farrier, making horseshoes and shoeing the animals in a courtyard at the front of Georgia and Ioannis’ house.

Children were born at home under the care of the village midwife, Chaido Synodinou (early-mid 1900s). A new mother was granted no reprieve from her tasks: cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Georgia’s mother, Amalia Bebetsos Zacharakis, boiled “bad” oil to make soap for washing clothes and bodies, and sold the product to earn a little money.

In addition to household chores, women harvested wheat and toiled in the fields. After the wheat was threshed, it was baked into bread in an outdoor oven.

Seeing the hardships endured by village women, Georgia’s father encouraged her to make a better life. With his blessing and support, Georgia studied dressmaking in Sparta and became an outstanding seamstress. She made clothing for men, women and children. She also constructed clothing and vestments for priests, which are both ornate and meticulously embroidered. Georgia’s love of sewing has not subsided, and she took great joy in showing us her two sewing machines.

Georgia’s brother, Pavlos, and her nephew, Nikolaos, shared memories of growing up in Theologos. People were very poor. When their fathers worked in the fields, they took only bread to eat, leaving the cheese at home for the children. Everyone — children and adults — went barefoot.

Children had handmade toys. Balls were made from old clothing tightly stuffed into socks. Stones were lined up, and the homemade balls were rolled to move them. Sticks of varying sizes were placed on a ledge with half of the stick extended over the edge. The stick was hit hard, and the one whose broken half flew the farthest won the game. Children played leap frog and “heads or tails” with a stone or small coin. Primary school was a one-room building in the village; secondary school was in Sparta.

In the mid-1900s, when children grew into young adults, they left the village to attend college in other areas of Greece. Some returned to the village; many did not. Around the time of the great emigration (early 1900s), men went overseas in search of new opportunities. They walked or took a horse and cart to the nearest port, Gytheion; from there, they boarded small ships to Piraeus and other ports for the journey across the Atlantic. After settling in a new land, they invited their siblings, cousins, and villagers to join them. They brought their sisters to be married, thus relieving parents of the burden of providing a dowry and finding husbands who could give their daughters a better life.

Today, the population of Theologos is about 200 people. Soon, our Zacharakis cousins will gather for a reunion and to enjoy being together. Many are waiting to see the updated family tree which I have compiled using civil and church records. As the plateia (town square) fills, I know our ancestors will rejoice when they see us, their descendants, uniting in remembrance of them.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.