What are the chances that a document which reveals an abstract branch of your family is given to you by a stranger? That’s exactly what happened to me on my recent journey to visit the ghost town of Vathia.

There is only one road that connects Sparta with Mani. Much of it follows the seaside of the Laconian Gulf, traversing through quaint villages and along scenic coastlines.This was the only way for me to reach my destination.

I stayed overnight in a lovely renovated tower house in Kokkala. The sea view was spectacular and the architecture and history of the towers always captivate me. This was the perfect place to stop on this journey, to rest and to soak in the beauty of Mani.

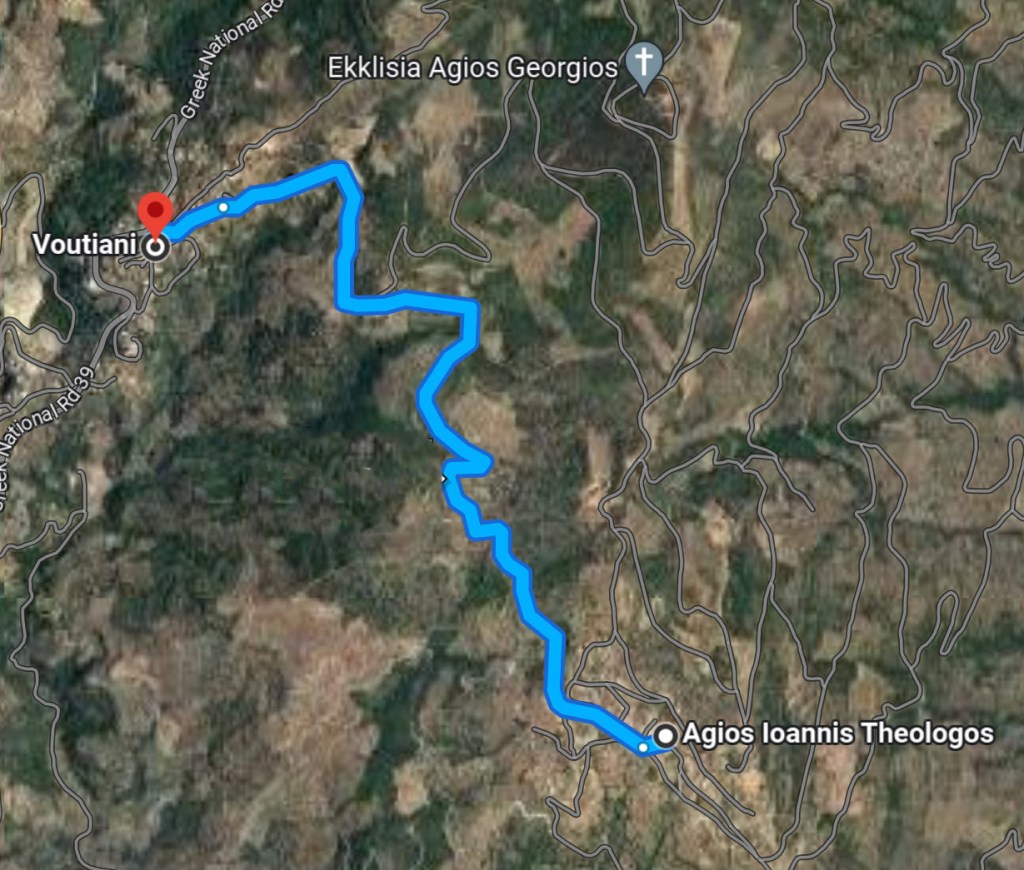

The next morning, I hit the road and with my sights set on Vathia. No stops were planned, and no side trips were considered. My focus was to spend as much time as possible in the ghost village, then return that night to Sparta. But along the way, I got sidetracked. About 1/2 hour south of Kokkala, I rounded a corner and there appeared a charming tower village nestled in the mountains. Lagia.

I hopped out to take photos, thinking that I would just breeze through the village and keep going. But when the road led into the plateia, there was something about the village that enticed me to stop. I parked the car and started walking.

The streets were deserted and the quiet of the village exuded a sense of tranquility. The imposing stone houses were of traditional Maniate style.

As is customary, the church, Koimisi tis Theotokou, was situated adjacent to the plateia. I went inside.

My heart was touched when I read a sign that was posted on the small icon stand situated at the entrance. It read:

Welcome to the Holy Temple of our village “Lagia.”

Look around you and visualize freely the hard efforts of our ancestors,

within a rough place with different values, principles and under adverse conditions,

who managed to complete the construction of this gorgeous Church.

This Temple was constructed before 200 years with the full participation of the local men and women, with building materials gathered from the surrounding mountains of the village and carried on their backs and shoulders.

It was built with main purpose the reconciliation and peace between the families of the village, as during that period of time confrontations, conflicts, frictions, disputes, and vendettas dominated the area.

It replaced and gathered under its protection all the local family churches, at about 30 small and picturesque, which were scattered all around between alleys, traditional towers and fields.

Support warmly the effort for the continuation, conservation, preservation, improvement and progression of this harbour of Love, Hope and Faith.

I became emotional, and I still don’t know why these words penetrated so deeply into my soul. Was it was the message of reconciliation and the fervent desire for peace? Was it the unity of 30 disparate church communities? Was it the sacrifices and the physical toil of the people to build this temple? Whatever it was, I was transfixed by Lagia.

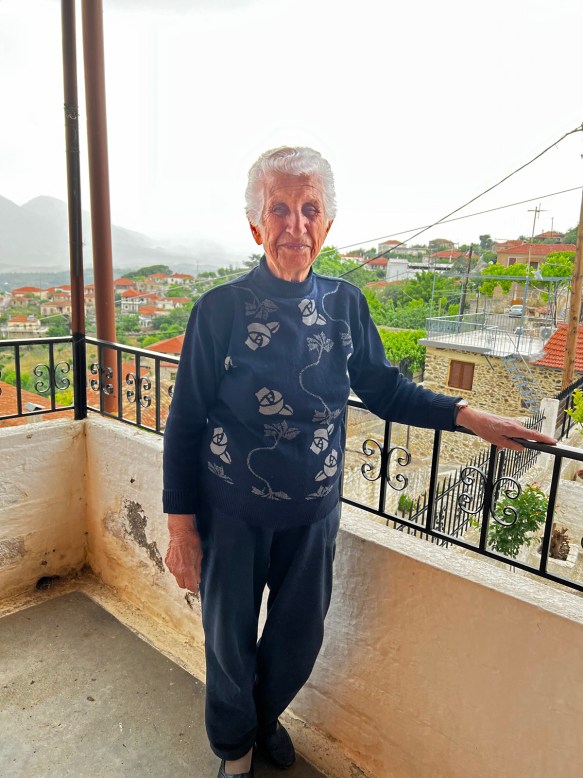

I was not ready to leave the village. As I walked around the plateia, I noticed three men sitting at a table at the cafenion. Normally I don’t start conversations with strangers, but something prompted me to do so this time. I said, in my very broken Greek, “You live in a beautiful village.” Their faces lit up, and the questions came: What is your name? Are you Greek? Where are your people from? When I told them that my family was from Sparta, the discussion grew quite animated. They asked for my surnames and as I responded, they commented on each one.

Kostakos? That name is found farther south, in Pakia (I knew that, but it’s a different family with the same patronymic surname).

Papagiannakos? Not in this village.

Eftaxias? That is an old family name found here.

That stopped me. I recalled that some years ago, my Eftaxias cousin in Mystras mentioned that there was a branch of the family in Lagia. Was it true? As my mind debated a possible connection, one of the men said, “We have a book inside that you should see.” He disappeared, then returned and handed me a spiral bound notebook.

I couldn’t believe what I was holding. It was the Male Register of Lagia, a list of every man born in the village during the years 1839-1888. I was given permission to photograph it, and I have made it available in a pdf file which can be downloaded here: Male Register of Lagia 1839-1888.

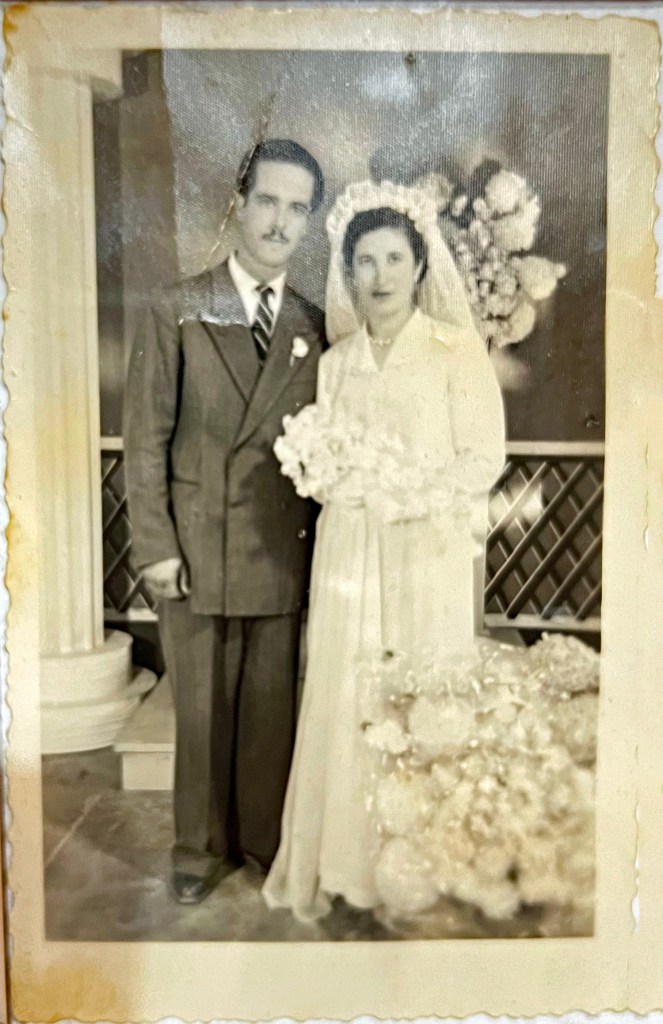

Eftaxias, Michail, father: Panagiotis, born in Lagia.

My cousin was correct. It was our family that was in this village. There was only one Eftaxias listed; he was found in the year 1882, line 124: Michail Panagiotis Eftaxias born in Lagia.

I am now able to correlate this family with previous but uncorrelated information found: Michalis Eftaxias from Lagia fought in the Revolution of 1821. He had a son named Vrettos, and Vrettos had two sons: Michalis (born 1826) and Panagiotis (born in 1832).1 Panagiotis, named above as the father of Michail, was the right age to be the son of Vrettos. With only one Eftaxias in the village, it had to be the same family. When I returned to Sparta, the Archive office gave me the Town Register for Eftaxias in Lagia which further documented this line.

I know that serendipitous things happen when you travel to the land of your ancestors and follow your instincts. Yet, whenever they do, I marvel that people are prompted to be in certain places, at certain times, to fulfill certain reasons. It is my hope that chance encounters, such as this, will also happen to you.

11875 Election Register of Lagia