by Theofanis G. Kalkanis

published in The Faris Newsletter, Issue 79, December 2023, page 8-9

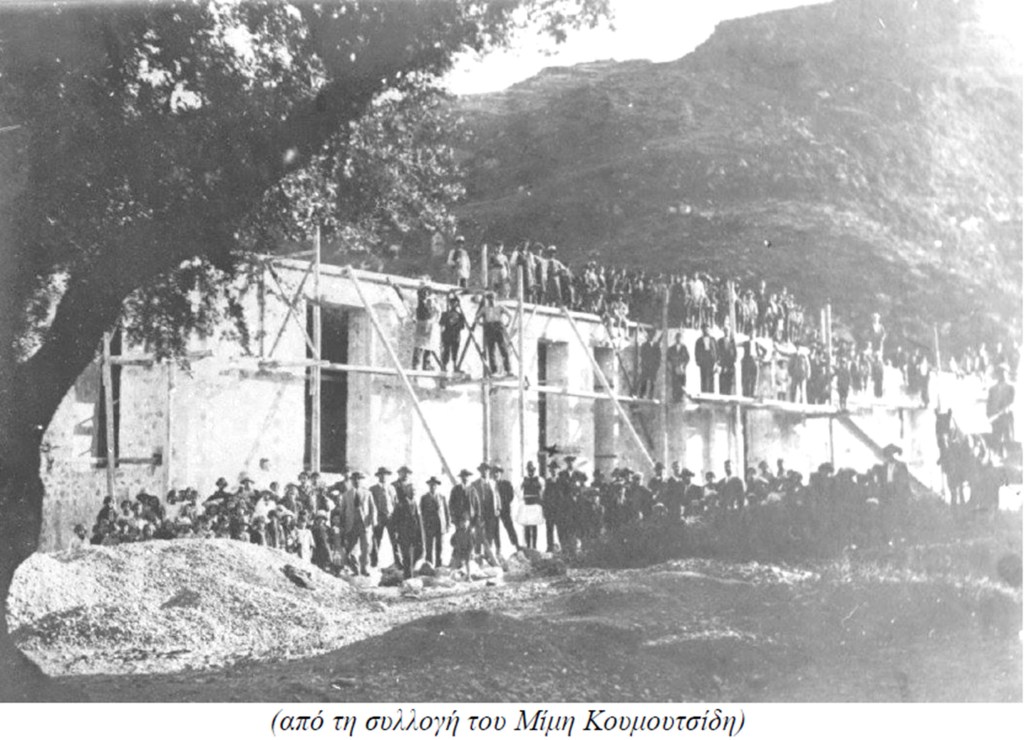

With the occasion of an old photograph I recently saw from the construction of the School Building in Xirokampi in 1927, I had some thoughts and observations as an engineer. At the same time, I remembered that until the 1970s in our villages (and not only), those who had built a house said the phrase of the title in every instance.

In the photograph, a crowd of people is depicted on the walls of the half-constructed building up to the first floor. They seem to celebrate the progress of the construction by wearing their best attire or even foustanellas. Some hold their tools and wear workers’ aprons. Everyone poses. Around the school, there is wood scaffolding. Piles of gravel and a few stones are scattered everywhere, but there is no lift [elevator] or machinery anywhere. Only a cart pulled by a horse. Obviously, the day of putting the concrete base of the first floor of the school will follow.

I thought about what would happen that day! Like every such day, many eyewitnesses remember that putting a cement building slab (also) in our villages, before the 1970s, required the mobilization of many artisans and workers. The whole village. It also required the coordination of many technical and manual tasks, culminating in a laborious and noisy effort (or celebration) for a day, with almost no mechanical support.

Each time, the processes of arranging the space preceded the placement of the concrete base, always done by hand using common tools, measurements with the paseto, [a folded wooden measuring stick], wooden supports, and moldings nailed with hammers. Molds to make metal rods [to reinforce the concrete] were created with concrete sticks that were cut and shaped on the spot by the craftsmen.

On the day of the slab casting, a crowd of workers with shovels made the mixture from cement and sand. Another larger group of workers carried “on their shoulders” bins of mud, climbing up to the level of the slab through narrow and shaky improvised stairs and scaffolding that slipped through the mud. Others smoothed the fluid mud with straight boards. Time was critical for the cement to set. So, with shouts coordinated by the elders, they created a feverish enthusiasm that encouraged the carriers to move quickly without stopping.

In contrast, today the same process is carried out quickly and nonstop by many mechanical means, with hoists, cranes, and tools operated by a few operators. However, it lacks the excitement and enthusiasm of the old “tilers.” Besides, in the past, the casting of the slab was boosted and completed soon by the anticipation of an informal, standing feast that followed, with dozens of herrings and countless jugs of wine passed from mouth to mouth. I think that what was happening then compared to what is happening today is a typical example of a “paradigm” shift for technology.

Returning to the photo, which was the trigger for this note, I remind you that the construction of the School Building in Xirokampi (1927-1929) was the fulfillment of a “vow” made by our compatriots who had fought in Asia Minor between 1918 and 1922 and returned alive.

I (Carol Kostakos Petranek) am honored to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the thirteenth article of the ongoing series. Previous articles can be viewed here.