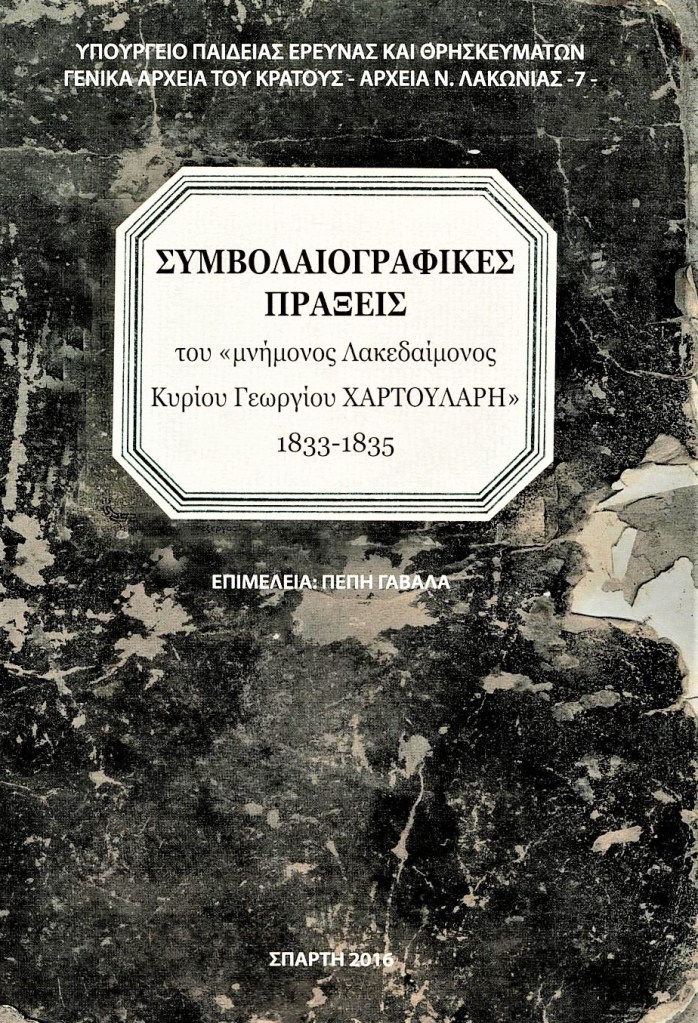

Knowing how important notary contracts are in finding information about our ancestors, I was very excited when Gregory Kontos of Greek Ancestry brought me a book published by Pepi Gavala, Archivist at the General State Archives of Greece, Sparta Office.[1] This book is not just a synopsis, but a full extract, of contracts from the collection of the notary, Georgios Chartoularis, 1833-1835.

I used the index to find entries of interest to me, and Gregory provided a synopsis of the contracts.

Here is an example: Contract 388, page 365-366; year 1834.

In the parish of Stavros in Mystras. Martha, daughter of the late Diamantis Dimitrakakis and wife of Anagnostis Dimakos. Martha had property which was part of her dowry. She wanted to sell the property to build a house in Mystras. Martha’s brothers and her nephew gave permission for her to sell the property to another nephew, Ilias Michalopoulos. It is unclear whether Martha’s brothers actually owned the property with her, or if they just gave permission for its sale.

Martha’s two brothers were: Theodorakis and Dimitrakis Diamantopoulos, sons of Diamantis [note: they took their father’s first name as their surname!]

Martha’s nephews [sons of her two sisters who are unnamed, but I now have her sisters’ married names]: Diamantis Panopoulos; and Ilias Michalopoulos the one to whom she sold her property.

Permission was given by Martha’s brothers, Theodorakis and Dimitrakis, and her nephew, Diamantis Panopoulos, to sell her property to her nephew, Ilias Michalopoulos.

The contract explains exactly where the property was located in Vitinarias, Mystras.

I was curious to learn some details about the property being sold, so I typed the contract into both Deepl and Google Translate. I was both surprised and confused when the word, αυτάδελφος, (relating to Martha’s brothers) appeared with different translations.

I looked in my Collins Greek-English dictionary and the word was not there.

I checked the dictionary, Λεξικό της ελληνικής ως ξένης γλώσσας, and the word was not there.

Babel Fish gave me the message: “failed translation.”

Microsoft/Bing translated the word as: self-brother (what does THAT mean?)

Systran: translated the word as: colleague

Βικιλεξικό: produced several definitions: self- brother <ancient greek αὐτάδελφος <αὐτός + ἀδελφός αυτοδελφος male (female cousin and cousin) brother (from both parents).

By this point, I was truly frustrated. Having the exact relationship is critical in genealogy research and I had many variations. Finally it dawned on me that this word, αυτάδελφος, used in 1833, may be obsolete in modern Greek. Giving it one last try, I went to the Google search bar and typed: What is the definition of αυτάδελφος? A “new to me” website, WordSense gave this definition: (rare) brother-german, full-brother. And under related words and phrases was: see αδελφός (masc.) (“brother”)

Intrigued, I clicked on brother-german, and found this definition: A full brother: a brother born to the same mother and father, as distinguished from half-brothers, step-brothers, or ‘brothers’ established through relationships such as wardship.

I went back to Greg and he confirmed that αυτάδελφος is obsolete and no longer used. He also said that old documents may use the term αθταδέλγη as full sister. Another colleague pointed out that ετεροθαλής is a half-brother.

Now I know why the printed and online dictionaries of MODERN GREEK do not have αυτάδελφος (it’s not a modern word!), and why online translation services mistranslated it.

Important lesson learned: when translating old documents, do not rely on online translations. They’re okay to get a general idea of the context of the document, but when it comes to important items such as relationships, ask Greek Ancestry for translation help. If Greg had not done the translation and I had relied solely on the translating tools, the relationships in my family tree would have been totally wrong, leading not only to misinformation but to utter confusion when corroborating evidence from various sources.

_______

[1] Gavala, Pepi. Notary book of Georgiou Cartoularis of Lakedaimonos, 1833-1835. Sparta, 2016. Contract #388, page 365