This is the final post of excerpts from the book, Amykles, by Sarantos P. Antonakos.

“With the Ottoman conquest, the Greeks could only preserve their identity by remaining steadfastly faithful to the Orthodox Church.” Steven Runciman[1]

Runciman’s observation answered a question I had long pondered: how did my ancestors ever survive four hundred years of Ottoman rule–a period of harsh military invasion and grim Muslim occupation? To these enslaved people, their Orthodox faith was far more than a religion.For twenty generations, Hellenes endured the unendurable by clinging tightly to their Christian beliefs and trusting in God for deliverance.

For this, they can thank St. Nikon.

St. Nikon,the Metanoeite. Wikipedia.

Nikon, the Metanoeite (preacher of repentance) re-introduced Christianity to parts of Greece. Born about 930 A.D. in Paphlagonia (an area in Asia Minor, currently northeast Turkey) he became a Byzantine monk and was sent abroad by his abbott to preach the gospel and teach the Bible. He began in Crete in 961, re-christianizing the citizens whose religion had lapsed under Muslim rule.

He then preached in Athens and Thebes, eventually arriving in the Peloponnese. His ministry extended from Naplion and Corinth to Laconia. His impact in Sparta was so profound that Antonakos describes his work and influence in a chapter titled, St. Nikon and Amykles, translated[2] excerpts below.

“After St. Nikon came to the area of Lacaedaimon, he beheld the Byzantine state ‘and these barbarian Christians.’ He built two churches: one in Sklavochori and one in Parori. The choice of these villages were not random. He built churches to fight the pagan influences. In Sklavochori was the ancient Temple of Apollo–a pagan center. Parori was occupied by Slavs who believed in other gods.

“Sparta became his second motherland and the base from which he taught the Holy Book throughout the whole Peloponnese. In Sparta and Lacedaimon (as it was well known back then), St. Nikon met great difficulties–first, from the reactions of the Jews and many corrupted people of Sparta; and on the other hand, he had difficulties spreading the Holy Book because of the Slavic influence in the western borders of Mani. St. Nikon was help by the bishop of Sparta, Theopemptos, and the great general of the Peloponnese, Vasileios Apokaukos.

“After St. Nikon established the two churches in Lacedaimon, he entered Mani, Kalamata, Methoni and others and he taught the faith of Christ. Returning to Sparta, he became sick and made a home in a cave in a location named Moros. After eight days when the Saint was good again, many people who had been there to receive his blessings became witnesses to a miracle that he did. The people were thirsty and there was no water in the area. St. Nikon, after praying, hit the land with his stick that had a cross on it and from the place he hit, much water started flowing like a spring, clean and clear and pure in taste.

“After the miracle, the Saint did not return to Sparta. He went to Amykles and people and elders came together to see him and they were inspired by him. In Amykles, St. Nikon found relief after physical exercise and spiritual testing. In this place, besides the spiritual power, we must add the love of the people of the village and their faith, something that St. Nikon was meeting very rarely in hostile areas around Sparta.The great respect of the people of Amykles towards St. Nikon can be proven from the fact that they were the first who came immediately by his invitation to help him build the temple of Sotiros at the Acropolis of Sparta. They gave him materials (limestone)–so much that some people said that it was taken from the ancient temple of Apollo in Amykles.

“A story is found in the monastery of Agios Tessarakonda in Sparta, written in the Will of this Saint: ‘Even as I many times was building one step, the next day I found two. The next I was building two and finding four. When I had many materials, a man came from Sklavochori and promised to help me, but he was lazy and the temple was not being built. One night, St. Sotiris came to that man in a dream and told him “I am going to take your soul.” The man asked why, and St. Sotiris said, “I am Sotiris, the one that Nikon is building the Temple for Lacedaimon. You promised him materials [that you did not bring] but your house is full of blessings. For this reason, you are lazy. Bring the materials and you will have profit.” The man brought materials to St. Nikon and they worked together.

“When the Spartans heard that St. Nikon was in Amykles, they ran to him, begging him to return to Sparta and with his blessing, to save the city from starvation that had killed many people. Nikon willingly returned. He banned the Jews from Sparta and they settled in Anavryti and Tripi.[3] Later, these Jews were christianized and adapted socially with the local people.

“After the movement of the Jews from Sparta, St. Nikon with the help of Bishop Theopemptos began to build a church devoted to Sotiros, the Theotokou and St. Kyriaki. A man named Aratos, who was doing business with the Jews, was against this. Aratos got a high fever and he died. After this miracle, many people adopted Christianity. In 981, St. Nikon went to Corinth where he healed the heavily injured Apokaukos [a general of high rank and political power, mentioned above]. Upon returning to Sparta, he performed more miracles.

“St. Nikon died in 998 and according to oral tradition, he was buried in Amykles. ‘His name is known in Lacedaimon in glory for mortal people and he is a spring of miracles.’ To the people in the land of Sparta, the Saint will forever be the ‘father and guardian‘ of them.”

During the Turkish occupation, St. Nikon’s ministry in Greece was generally forgotten except in Sparta. After the Revolution of 1821, Father Daniel Georgopoulos composed a service honoring the Saint. In 1893, the Diocese of Monemvasia and Lacedaimonia recognized him as their patron saint when a church in Sparta was dedicated to him. His life is commemorated yearly on November 26.

Antonakos’ history of Amykles has captured the times, spirit and resiliency of these extraordinary people. The more I read, the more I want to learn! I have been counseled by a wise teacher that we must first know the history before we can understanding our ancestors. And, I might add, ourselves.

***

In 1982, Sarantos P. Antonakos published Amykles, a history book about his native village. Amykles is one of my ancestral villages, too–the birthplace of my 3rd great grandfather, Panagiotis Zarafonitis. I am beyond excited to have found this book in the Central Library of Sparta, and I copied some of the pages relevant to my family. With sincere thanks to Giannis Michalakakos for his translations and history lessons, I am learning much about this beautiful village and the lives of my ancestors.

To read part one about the village of Sklavochori, click here.

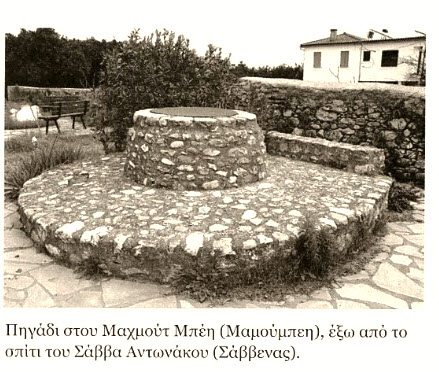

To read part two about Machmoutbei, click here.

To read part three about the Battle of Machmoutbei, click here.

__________

[1] Runciman, Steven. The Lost Capital of Byzantium: The History of Mistra and the Peloponnese. 2009: Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp. 102-103.

[2] My deepest appreciation to Giannis Michalakakos for his translations.

[3] Andonakos’ perspective on this issue: there was a Jewish presence in Mystras because the city was a commercial center. When St. Nikon began proselyting, this caused both religious and political tensions between the Jews and the Orthodox church. When sickness and starvation permeated Sparta, St. Nikon attributed that to the Jews, using this opportunity to ban them from Sparta and send them to Anavryti and Tripi.