by Charilaou N. Stavrogianni

published in The Faris Newsletter Issue 74, July 2021, pages 8-9

The area around Konstantinos Plainos’s house down to the Rasina river was called Mylovagena because of the pre-existing watermill there.

Source: Lakonika.gr

Many times I think of a visit with my mother to get our flour from the mill when I was a small child. Arriving there I heard a loud noice which came from the waterfall through the basins. This made me afraid. Entering into a low-ceilinged, dimly lit room and seeing white dust floating, I became even more afraid, culminating with the appearance of a human shadow full of flour dust. Finally this human shadow came and stood beside me and began to stroke the hair on my head. As he spoke to me, I realized it was my grandfather, the miller of the watermill, who had rented the mill from the monastery of Zerbitsa. Then he loaded our flour onto our animal, which we had tied outside the watermill to a thick wooden post placed there for this purpose, lifted me onto the animal’s saddle between the two sacks of flour, and my mother and I took the road back, which made me feel great relief from the fear that had overtaken me inside the mill.

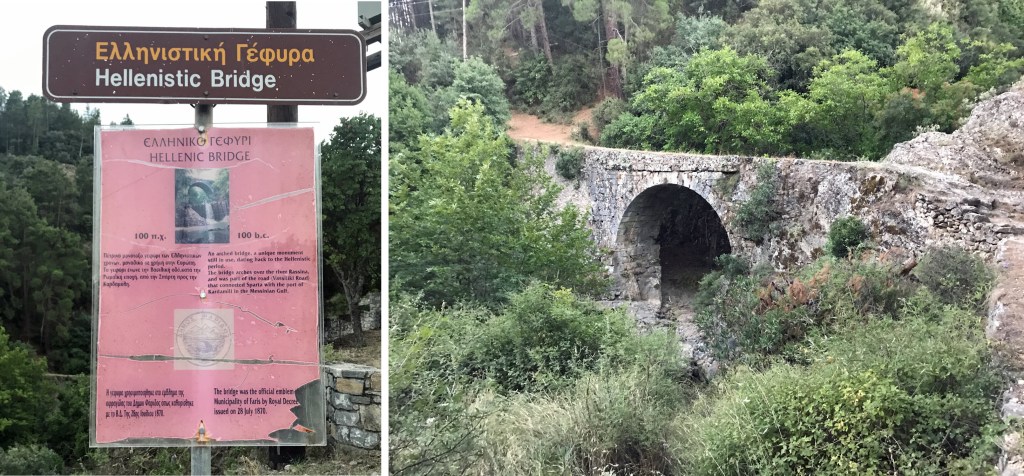

Later, when I was a much older child, I would ask my grandfather to explain to me the the entire process and operation of the mill. He told me that the miller’s biggest problem was the water, which was the driving force for the mill to work. The water came to the mill through a large earthen channel, called the milavlako. It started just under the arch of the Greek Bridge. That is where the dam was.

He would also tell me: To divert the water, I would climb on the rocks and cut branches of mastic and holly trees and place them in the river water, weigh them down with large stones, and pray to God, making my cross, that the river wouldn’t regularly flood and wash away my dam and I would have to start all over again. This must be how the saying arose “Everyone cries about their pain and the miller about his ditch.”

The milavlako with its abundant water passed over a concrete bridge exactly before and above the mill, so that the road would not be closed and and to form the appropriate height. In the past, before cement, the bridge was constructed with thick boards. On the bridge somewhere in the middle there was a divider for the miller to distribute the water as he wished, before it fell into the barrels. The vats had large, tall openings and were made of thick sheet metal with many external metal rings to withstand the water pressure. From these came the name Mylovagena. The water fell with great pressure and force through the vat onto the wheel, which was a propeller of thick pine boards, which the miller obtained from the woodcutters of Koumusta. The powerful fall of water continuously rotated the wheel, whose axle turned the upper horizontal cylindrical millstone. The bottom stone remained stationary. The miller would pour the wheat through a hole in the center of the upper rotating millstone. With this motion the wheat would break, being crushed between the two millstones and become flour. The producer paid the miller a fee of 8-10% on the quantity of flour, exactly as is done in today’s olive mills.

Source: Δ. Αβούρης, Lakonika.gr

The watermill area was sold shortly after 1950 by the abbess of the Nymphodora monastery, in order to build the building that housed the looms and is today the monastery’s guest house. The mill with all the surrounding area was bought by Stratigis Solomos. Perhaps the mill worked a little longer. After all, the new owner had his own flour mill. Shortly before 1980 the mill was sold again by G. Venetsakos, a primary school teacher from Potamia, who had received the mill from Solomos as dowry.

Today in area around the mill and on both sides of the road, there are two houses. In less than thirty years the mill changed hands four times. Outside the mill there was also the most beautiful well of Xirokampi. Its external appearance was square with beautifully carved pistachio colored stones. Today it does not exist. It seems we did not like the tradition. The only thing that has remained from Mylovagena is the stone staircase, which went down to the mill and the well.

On the Greek islands, where there was not plenty of water but there was plenty of but strong air, the so-called windmills operated. Some are still in operation today.

In almost all the villages of our region there were also household hand mills. These were two horizontal cylindrical millstones, naturally small in size and weight so they could be moved easily. The bottom millstone always remained stationary and at the edge of the top there was a small hole, where a wooden handle was placed, hence the hand mill. In the middle there was a larger hole, where they would drop the wheat. As the top millstone rotated, the wheat was coarsely ground, exactly as they wanted to make sweet couscous and then in the winter the delicious pumpkin pies in the wood-fired oven of the house. The hand mill was a miniature of the watermill and, instead of water as a driving force, it had the power of a human woman’s hand.

It would be an omission to forget the coffee mills. Many times I remember the grandmothers, who with a metal device, the so-called mill, would grind coffee beans in the evenings in the fireplace of their house and the whole neighborhood would smell of coffee beans. To increase the quantity of coffee and for health reasons they would also throw chickpea seeds into the roaster. Today the mills that once ground coffee decorate a shelf or other place in the house as antique souveniers.

Tradition tells many stories and tales about millers and watermills. Also many proverbs, such as: “Everyone cries about their pain and the miller about his channel”, “Without water the mill does not turn”, “A good mill grinds everything.”

Writing the last proverb, I remembered what my grandfather would tell me: During the difficult and poor years of the Occupation and the subsequentl civil strife, in order to survive the watermills had to grind not only wheat and corn, but even barley, lupines and acorns, after drying the latter in the oven. The last three types, without mixing wheat flour and wheat-corn flour, produced very bad black and bitter bread. During the latter part of my life I had heard many times the phrase: “I ate or have eaten the bitter bread of Occupation.”

NOTE: Additional information about the mills of Talanta (Monemvasia), Lakonia can be found in this article at Lakonikos.gr.

__

I (Carol Kostakos Petranek) am honored to receive permission from the Katsoulakos family to translate and share articles from The Faris. Translation verification and corrections have been made by GreekAncestry.net. This is the twentieth article of the ongoing series. Previous articles can be viewed here.